Face of oldest human ancestor comes into focus with new fossil skull

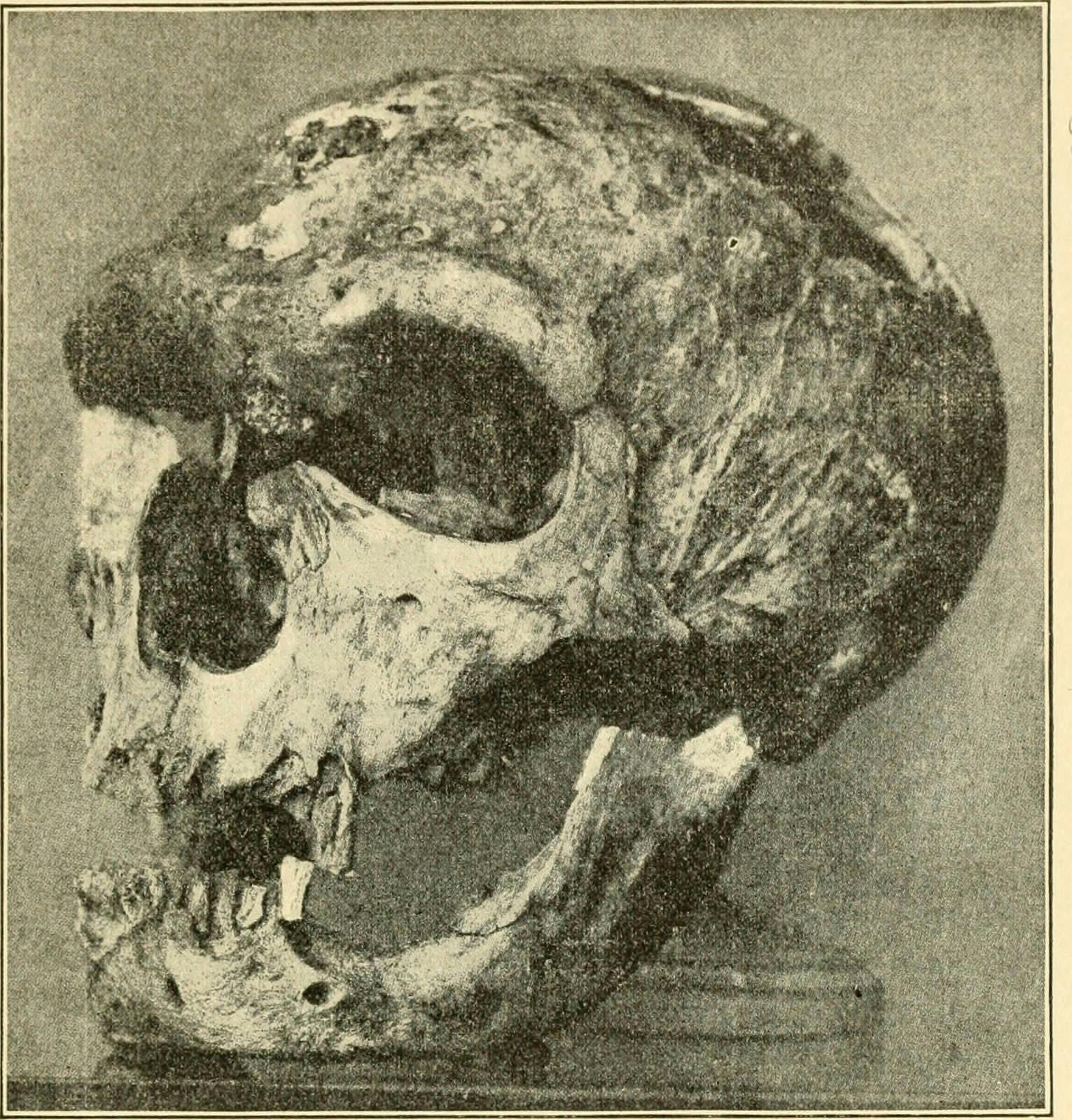

A new fossil discovery means we’re finally able to look upon the face of our oldest ancestor. Paleontologists have discovered an almost-complete skull of Australopithecus anamensis, which has previously only been known from some jawbones, teeth and bits of leg bones. The new find allowed scientists to realistically recreate the hominin’s face for the first time – and it might just shake up the family tree.

The face of this long-lost ancestor is strangely familiar, not least because of the eerily human eyes. But those – along with the leathery brown skin and muttonchop beard – are the kind of best-guess embellishments you’d expect from a recreation like this. Other features, like the large flat nose, the protruding rounded jaw, and prominent brows and cheekbones, are based on the most complete skull of its kind ever found.

Discovered in Ethiopia in 2016, the skull has been dated to 3.8 million years old and attributed to an adult male specimen of Australopithecus anamensis. Interestingly, that makes it both the youngest fossil of A. anamensis known – which are believed to have lived between 4.2 and 3.9 million years ago – and one of the oldest cranial remains of hominins, which tend to dry up in the fossil record before about 3.5 million years ago.

This new find fills an important gap in the human origin story. A. anamensis is the oldest known species in the Australopithecus genus, who are considered the earliest members of the human evolutionary tree. It’s long been accepted that A. anamensis directly evolved into another subspecies, A. afarensis – the most famous example of which is Lucy herself.

But with this new skull, scientists have far more pieces of the puzzle and have realized that they may have previously been putting them together wrong.

The researchers were able to determine which species the skull belonged to by comparing it to the previously-discovered teeth, jaws and other fragments. The rest of the skull showed a strange mix of primitive and advanced (or “derived”) features. Most interesting is the fact that some of the features on A. anamensis are actually more advanced than those on A. afarensis. That calls into question the long-standing idea that the former evolved directly into the latter.

The revised timeline they created says that A. anamensis lived until at least 3.8 million years ago, while A. afarensis arose earlier than previously thought – maybe as early as 3.9 million years ago. Doing the math, that suggests that the two species may have overlapped by as much as 100,000 years.

Once again, it seems like our evolutionary history needs a rewrite. A more complete fossil record can help us patch up holes and revise what we thought we knew.

The research was described in two papers published in the journal Nature. The researchers describe the find in the video below.

The Face of Lucy’s Ancestor Revealed

(For the source of this, and many other interesting articles, and to watch a video associated with it, please visit: https://newatlas.com/science/oldest-human-ancestor-skull-face-reconstruction/)

Traces of two unknown archaic human species turn up in modern DNA

Although we won the race to many corners of the world, modern humans weren’t necessarily the first hominins to leave Africa. It’s long been known that more archaic species like Homo heidelbergensis beat us into Asia and Europe, where they eventually split into sub-species like Neanderthals and Denisovans.

By the time Homo sapiens made it into these regions, other species already called it home. What happened next was only natural – humans bred with these other species.

“Each of us carry within ourselves the genetic traces of these past mixing events,” says Dr João Teixeira, first author of the study. “These archaic groups were widespread and genetically diverse, and they survive in each of us. Their story is an integral part of how we came to be.

“For example, all present-day populations show about two percent of Neanderthal ancestry which means that Neanderthal mixing with the ancestors of modern humans occurred soon after they left Africa, probably around 50,000 to 55,000 years ago somewhere in the Middle East.”

The team identified the islands of Southeast Asia as a particular hotbed of this interbreeding, with modern humans cozying up to at least three different archaic species. One of them is the Denisovans, which have previously been identified in the genomes of people of Asian, Melanesian and indigenous Australian descent. But the other two remain unidentified.

The researchers reconstructed migration routes and examined fossil vegetation records, and suggested the likely locations of these two mixing events. The first appears to have occurred around southern Asia, between modern humans and an unknown group the team is calling Extinct Hominin 1.

The second seems to have occurred around East Asia, the Philippines, and Indonesia, with a group dubbed Extinct Hominin 2.

“We knew the story out of Africa wasn’t a simple one, but it seems to be far more complex than we have contemplated,” says Teixeira. “The Island Southeast Asia region was clearly occupied by several archaic human groups, probably living in relative isolation from each other for hundreds of thousands of years before the ancestors of modern humans arrived. The timing also makes it look like the arrival of modern humans was followed quickly by the demise of the archaic human groups in each area.”

This isn’t the first time clues to unknown human species have turned up in our own DNA. A recent study found evidence of a “ghost” species in human saliva samples, DNA from an as-yet-unknown relative was found in the “dark hearts” of our chromosomes, and genetic studies on an Alaskan fossil revealed a previously-unknown population of Native Americans.

The research was published in the journal PNAS.

Source: University of Adelaide

(For the source of this, and many additional important articles, please visit: https://newatlas.com/archaic-human-species-dna/60601/)

FaceApp Uncannily Captures These Classic Biological Signs of Aging

A guide to what it is, exactly, that makes faces look so old.

This week, celebrities ranging from the Jonas Brothers to Ludacris gave us a peek into what they might look like in old age, all with the help of artificial intelligence. But how exactly has FaceApp taken a stable of celebrities and transformed them into elderly versions of themselves? The app may be powered by A.I., but it’s informed by the biology of aging.

FaceApp was designed by the Russian company Wireless Lab, which debuted the first version of the app back in 2017. But this new round of photos is particularly detailed, which explains the app’s resurgence this week. Just check out geriatric Tom Holland, replete with graying hair and thickened brows — and strangely, a newfound tan.

What tweaks does FaceApp make to achieve that unforgiving effect? On the company’s website, the explanation is fairly vague: “We can certainly add some wrinkles to your face,” the team writes. But a closer look at the “FaceApp Challenge” pictures shows that it does far more than that.

FaceApp has been tight-lipped about how its software works — though we know it’s based on a neural network, a type of artificial intelligence. Inverse has reached out to FaceApp for clarification about how the company achieves its aging effects and will update this story when we hear back.

Regardless, scientists have been studying the specific markers of facial aging for decades, which give us a pretty good idea of what changes FaceApp’s neural network takes into consideration when it transports users through time.

The Original FaceApp

Before there was FaceApp, there was Rembrandt, a 17th-century Dutch painter who had a thing for highly unforgiving self portraits, about 40 of which survive today.

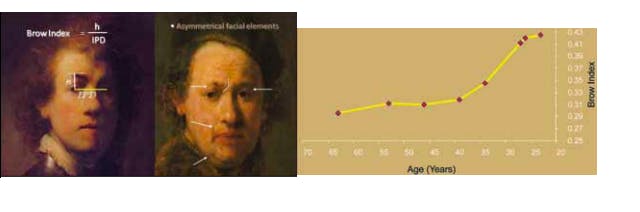

In 2012, scientists in Israel performed a robust facial analysis on Rembrandt’s work that was initially intended to separate the real paintings from forgeries. But their paper, published in The Israel Medical Association Journal, also incorporated “subjective and objective” measures of facial aging that they used to measure the impacts of time on the artist’s face. These measures have some applications to our modern-day FaceApp images.

Their formula focused on wrinkles that highlighted Rembrandt’s increasing age. Those included forehead and glabellar wrinkles — the wrinkles between the eyes that show up when you furrow your brow but seem to stick around later in life. They also analyzed accumulations of loose skin around the eyelids, called dermatochalasis (which creates “bags”), and nasolabial folds, which are the emergence of “smile lines” between the nose and mouth.

Fortunately, Rembrandt’s commitment to realism also gave them bigger aging-related features to work with. They quantified his “jowl formation” and the development of upper neck fat. But the most powerful metric was their “brow index,” which, over time, documented a descending brow line in the artist. Rembrandt’s eyebrows really descended starting in his ‘20s but leveled out by his ‘40s.

We can see some of the similar markers in these current FaceApp images. Just look at the aged Tottenham Hotspur squad, complete with furrowed brows, eye bags, and descending jowls — just like Rembrandt.

What Makes a Face Look Older?

Wrinkles notwithstanding, there is another way that FaceApp may be working its magic. There’s some evidence that perceived age is partially linked to facial color contrast.

Also, in 2012, a team of scientists in France and Pennsylvania demonstrated the impact of contrast in a series of experiments on images of female, caucasian faces. Faces with high color contrast among facial features (eyes, lips, and mouth, for example) and the skin surrounding them tended to appear younger than faces with low contrast in those areas.

In 2017, members of that team published another study suggesting that contrast holds information about age across ethnic groups. There, they found that color contrast of facial features decreased with age across groups, but most significantly in Caucasian and South Asian women. Contrast decreased with age in Chinese and Latin American women, too, but not as strongly.

Importantly, they also note that when you artificially enhance contrast, faces tend to look younger as well, suggesting that contrast’s relationship to age perception is strong.

“We have also found that artificially increasing those aspects of facial contrast that decrease with age in diverse races and ethnicities makes the faces look younger, independent of the ethnic origin of the face and the cultural origin of the observers,” they write.

Let’s take a closer look now.

Now that we know all this, let’s take another look at those photos of Tom Holland. There does seem to be some kind of color manipulation going on, in addition to the obvious wrinkling of his skin, though it’s unclear if maybe the photo was altered after FaceApp was applied.

Still, color contrast and specific physical features (like “jowl formation”) are factors that may be contributing to FaceApp’s seemingly magical transformation of age — which, for now, has captivated the internet.

(For the source of this, and many other interesting articles, please visit: https://www.inverse.com/article/57787-faceapp-challenge-signs-of-biological-aging/)

Why Do We Procrastinate? Scientists Pinpoint 2 Explanations in the Brain

Scientists find biological evidence that it’s not just about laziness.

There are an infinite number of excuses for putting off your to-do list. Letting clutter build up feels easier than Marie Kondo-ing the whole house, and filing your taxes on time can feel unnecessary when you’ll probably get an extension. The roots of this common but troubling habit run deep. In early July, a team of German researchers showed that procrastination’s root cause is not sheer laziness or lack of discipline but rather, a surprising factor deep in the brain.

In the strange study published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, scientists at Ruhr University Bochum argue that the urge to procrastinate is governed by your genes.

“To my knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the genetic influences on the tendency to procrastinate,” first author and biopsychology researcher Caroline Schlüter, Ph.D., tells Inverse.

In the team’s study of 287 people, they discovered that women who carried one specific allele (a variant of a gene) were more likely to report more procrastination-like behavior than those who didn’t.

Where Does Procrastination Come From?

The team, led by Erhan Genc, Ph.D., a professor at the university’s biopsychology department, has been studying how procrastination might manifest in the brain for several years. His brain-based data suggests procrastination is more about managing the way we feel abut about tasks as opposed to simply managing the time we have to dedicate to them.

In 2018, Genc and his colleagues published a study that linked the amygdala, a brain structure involved in emotional processing, to the urge to put things off. People with a tendency to procrastinate, they argued, had bigger amygdalas.

“Individuals with a larger amygdala may be more anxious about the negative consequences of an action — they tend to hesitate and put off things,” he told the BBC.

In the new study, the team tried to identify a genetic pattern underlying their discovery about bigger amygdalas. They believe they’ve found one affecting women specifically. The gene they highlight affects dopamine, a neurotransmitter central to the brain’s reward system that’s implicated in drug use, sex, and other pleasurable activities.

In particular, the gene encodes an enzyme called tyrosine hydroxylase, which helps regulate dopamine production. Women who carried two copies of a variant of that gene, they showed, produce slightly more dopamine than those with an alternative version of the gene and they also tended to be “prone to procrastination,” according to self-reported surveys.

While this is hardly a causal relationship, the authors argue that there’s a connection between the tendency to procrastinate and this gene that regulates dopamine in the brain, at least in women.

They note, however, that this connection probably exists outside of the one highlighted in their earlier study on the amygdala. When they investigated whether there was a connection between the genotype of procrastinators and brain connectivity in the amygdala, they found no significant correlation.

“Thus, this study suggests that genetic, anatomical and functional differences affect trait-like procrastination independently of one another,” they write.

In other words, there is probably more than biological process that underpins procrastination, and these researcher suggest that they may have identified two of them so far.

Why Might Dopamine Influence Procrastination?

Despite its well-known link to pleasure, dopamine’s role in procrastination may not come down to its primary role. As Genc notes, dopamine is also related to “cognitive flexibility,” which is the ability to juggle many different ideas at once or shift your thinking in an instant. While this is helpful for multitasking, the team argues that it might also make someone more prone to being distracted.

“We assume that this makes it more difficult to maintain a distinct intention to act,” says Schlüter. “Women with a higher dopamine level as a result of their genotype may tend to postpone actions because they are more distracted by environmental and other factors.”

It would be a long jump to suggest that one gene related to dopamine production affects all of the complex factors governing human procrastination. There are almost certainly a range of different factors at play that may have influenced their results, notably the hormone estrogen, seeing as the pattern was only found in women. But hormones and neurotransmitters aside, the urge to procrastinate likely comes down to more than just genetic signatures. Sometimes, life just gets in the way.

Media via Pixabay, Inverse, Unplash/ Sander Smeekes

(For the source of this, as well as many other important and interesting articles, please visit: https://www.inverse.com/article/57577-why-do-we-procrastinate-biological-explanations/)

Advice to yourself

What advice would you give your younger self? This is the first study to ever examine it.

- A new study asked hundreds of participants what advice they would give their younger selves if they could.

- The subject matter tended to cluster around familiar areas of regret.

- The test subjects reported that they did start following their own advice later in life, and that it changed them for the better.

Everybody regrets something; it seems to be part of the human condition. Ideas and choices that sounded good at the time can look terrible in retrospect. Almost everybody has a few words of advice for their younger selves they wish they could give.

Despite this, there has never been a serious study into what advice people would give their younger selves until now.

Let me give me a good piece of advice

The study, by Robin Kowalski and Annie McCord at Clemson University and published in The Journal of Social Psychology, asked several hundred volunteers, all of whom were over the age of 30, to answer a series of questions about themselves. One of the questions asked them what advice they would give their younger selves. Their answers give us a look into what areas of life everybody wishes they could have done better in.

Previous studies have shown that regrets tend to fall into six general categories. The answers on this test can be similarly organized into five groups:

- Money (Save more money, younger me!)

- Relationships (Don’t marry that money grabber! Find a nice guy to settle down with.)

- Education (Finish school. Don’t study business because people tell you to, you’ll hate it.)

- A sense of self (Do what you want to do. Never mind what others think.)

- Life goals (Never give up. Set goals. Travel more.)

These pieces of advice were well represented in the survey. Scrolling through them, most of the advice people would give themselves verges on the cliché in these areas. It is only the occasional weight of experience seeping through advice that can otherwise be summed up as “don’t smoke,” “don’t waste your money,” or “do what you love,” that even makes it readable.

A few bits of excellent counsel do manage to slip through. Some of the better ones included:

- “Money is a social trap.”

- “What you do twice becomes a habit; be careful of what habits you form.”

- “I would say do not ever base any decisions on fear.”

The study also asked if the participants have started following the advice they wish they could have given themselves. 65.7% of them said “yes” and that doing so had helped them become the person they want to be rather than what society tells them they should be. Perhaps it isn’t too late for everybody to start taking their own advice.

Kowalski and McCord write:

“The results of the current studies suggest that, rather than just writing to Dear Abby, we should consult ourselves for advice we would offer to our younger selves. The data indicate that there is much to be learned that can facilitate well-being and bring us more in line with the person that we would like to be should we follow that advice.”

(For the source of this, and many other important articles, please visit: https://bigthink.com/personal-growth/advice-to-younger-self/)

Emotional temperament in babies associated with specific gut bacteria species

A new study from the University of Turku has uncovered interesting associations between an infant’s gut microbiome composition at the age of 10 weeks, and the development of certain temperament traits at six months age. The research does not imply causation but instead adds to a compelling growing body of evidence connecting gut bacteria with mood and behavior.

It is still extraordinarily early days for many scientists investigating the broader role of the gut microbiome in humans. While some studies are revealing associations between mental health conditions such as depression or schizophrenia and the microbiome, these are only general correlations. Evidence on these intertwined connections between the gut and brain certainly suggest a fascinating bi-directional relationship, however, positive mental health is certainly not a simple a matter of taking a certain probiotic supplement.

Even less research is out there examining associations between the gut microbiome and behavior in infants. One 2015 study examined this relationship in toddlers aged between 18 and 27 months, but this new study set out to investigate the association at an even younger age. The hypothesis being, if the early months in a young life are so fundamental to neurodevelopment, and our gut bacteria is fundamentally linked with the brain, then our microbiome composition could be vital in the development of basic behavioral traits.

The study recruited 303 infants. A stool sample was collected and analyzed at the age of two and a half months, and then at around six months of age the mothers completed a behavior questionnaire evaluating the child’s temperament. The most general finding was that greater microbial diversity equated with less fear reactivity and lower negative emotionality.

“It was interesting that, for example, the Bifidobacterium genus including several lactic acid bacteria was associated with higher positive emotions in infants,” says Anna Aatsinki, one of the lead authors on the study. “Positive emotionality is the tendency to experience and express happiness and delight, and it can also be a sign of an extrovert personality later in life.”

On a more granular level the study homed in on several specific associations between certain bacterial genera and infant temperaments. High abundance of Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus, and low levels of Atopobium, were associated with positive emotionality. Negative emotionality was associated with Erwinia, Rothia and Serratia bacteria. Fear reactivity in particular was found to be specifically associated with an increased abundance of Peptinophilus and Atopobium bacteria.

The researchers are incredibly clear these findings are merely associational observations and no causal connection is suggested. These kinds of correlational studies are simply the first step, pointing the way to future research better equipped to investigate the underlying mechanisms that could be generating these associations.

“Although we discovered connections between diversity and temperament traits, it is not certain whether early microbial diversity affects disease risk later in life,” says Aatsinki. “It is also unclear what are the exact mechanisms behind the association. This is why we need follow-up studies as well as a closer examination of metabolites produced by the microbes.”

The new study was published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.

Source: University of Turku

(For the source of this, and many other important articles, please visit: https://newatlas.com/gut-bacteria-microbiome-baby-infant-behavior-mood/60197/)

Released in the same year as The Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Henry Hathaway’s western was defiantly old-fashioned in comparison

The year 1969 was a true inflection point for the American western, a once-dominant genre that had become a casualty of the culture, particularly when Vietnam had rendered the moral clarity of white hats and black hats obsolete. A handful of westerns were released by major studios that year, including forgettable or regrettable star vehicles for Burt Reynolds (Sam Whiskey) and Clint Eastwood (Paint Your Wagon), who were trying to revitalize the genre with a touch of whimsy. But 50 years later, three very different films have endured: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Wild Bunch and True Grit. Together, they represented the past, present and future of the western.

In the present, there was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the year’s runaway box-office smash, grossing more than the counterculture duo of Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider, the second- and third-place finishers, combined. George Roy Hill’s hip western-comedy, scripted by William Goldman and starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, turned a story of outlaw bank robbers into a knowing and cheerfully sardonic entertainment that felt attuned to modern sensibilities. Sam Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch predicted a future of revisionist westerns, full of grizzled antiheroes, great spasms of stylized violence, and the messy inevitability of unhappy endings. A whiff of death from a genre in decline.

By contrast, True Grit looks like it could have been released 10, 20 or 30 years earlier, and with many of the same people working behind and in front of the camera. Its legendary producer, Hal B Wallis, was the driving force behind such Golden Age classics as Casablanca and The Adventures of Robin Hood, and his director, Henry Hathaway, cut his teeth as Cecil B DeMille’s assistant on 1923’s Ben Hur before spending decades making studio westerns, including a 1932 debut (Heritage of the Desert) that gave Randolph Scott his start and seven films with Gary Cooper. And then, of course, there’s John Wayne as Rooster Cogburn, stretching himself enough to win his only Oscar for best actor, but drawing heavily on his own pre-established iconography. It was, for him, a well-earned victory lap.

True Grit may be defiantly old-fashioned and stodgy when considered against the films of the day, but it’s also an example of how durable the genre actually was – and how it would be again in 2010, when the Coen brothers took their own crack at Charles Portis’s 1968 novel and produced the biggest hit of their careers. What would be more escapist than ducking into a movie theater in the summer of ’69 and stepping into a time machine where John Wayne is a big star, answering a call to adventure across a beautiful Technicolor expanse of mountains and prairies? The film has much more sophistication than the average throwback, but the search for justice across Indian Territory is uncomplicated and righteous, and the half-contentious/half-sentimental relationship between a plucky teenager and an irascible old coot grounds it in the tried-and-true. The defiant message here is: this can still work!

And boy does it ever. Kim Darby didn’t get much of a career boost for playing Mattie Ross, a fiercely determined and morally upstanding tomboy on the hunt for her father’s killer, but every bit of energy and urgency the film needs comes from her. When Mattie’s father is shot by Tom Chaney (Jeff Corey), a hired hand on their ranch near Fort Smith, Arkansas, she takes it upon herself to make sure he’s caught and dragged before the hanging judge. Whatever emotion she feels about the loss is set aside, limited to a brief crying jag in the privacy of a hotel bedroom, and she’s all business the rest of the time. When the Fort Smith sheriff doesn’t seem sufficiently motivated, she seeks out US marshal Cogburn (Wayne), a one-eyed whiskey guzzler who lives alone with a Chinese shopkeep and a cat he calls General Sterling Price.

The odd man out in their posse is a Texas ranger named La Boeuf (Glen Campbell), which Wayne and everyone else pronounce as “La Beef”, as part of his instinctual disrespect for Texans – and, really, anyone who fought for the Confederacy during the civil war. (La Boeuf makes a point of saying he fought for General Kirby Smith, rather than the south, which suggests a sense of shame that stands out in our current age of tiki-torch monument protests.) The chemistry between the three is terrific, despite Campbell’s limitations as an actor, because it’s constantly changing: Rooster and La Boeuf are sometimes aligned as mercenaries who see Chaney as a chance to take money from Mattie and from the family of a Texas state senator that the scoundrel also shot. Rooster comes to Mattie’s defense when Le Boeuf treats her like a wayward child and whips her with a switch, but the tables turn on that, too, when Rooster’s protective side holds her back.

Wayne called Marguerite Roberts’ script the best he’d ever read – she was on the Hollywood blacklist, which made them odd political bedfellows – and True Grit has nearly as much pop in the dialogue as the showier Butch Cassidy. Mattie gets to turn her father’s oversized pistol on Chaney, but language is her weapon of choice, delivered in such an intellectual fusillade that her adversaries tend to surrender quickly. (A running joke about the lawyer she intends to sic on them has a wonderful payoff.) The three leads exchange playful barbs and colorful stories, too, with Rooster ragging on La Boeuf’s marksmanship (“This is the famous horse killer from El Paso”) or spending the downtime before an ambush sharing the troubled events from his life that have gotten him to this place.

There’s a degree to which True Grit is a victory lap for Wayne, who gets one of his last – and certainly one of his best – opportunities to pay off a career in westerns. Yet Wayne genuinely lets down his guard in key moments and allows real pain and vulnerability to seep through, enough to complicate his tough-guy persona without demolishing it altogether. It may not have the gravitas of Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven, but it’s the same type of performance, the reckoning of a western gunslinger who’s seen and done terrible things, lost the people he loved, and seems intent on living out his remaining days alone. Without the redemptive power of Mattie’s kindness and decency, True Grit is about a man left to drink himself to death.

(For the source of this, and many other quite interesting articles and features, please visit: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/jun/11/true-grit-john-wayne-1969-henry-hathaway/)

John Wayne – Very brief partial bio:

John Wayne was born Marion Robert Morrison in Winterset, Iowa on May 26th, 1907. He attended the University of Southern California (USC) on an athletic scholarship. But he broke his collarbone which ended his athletic career. That accident also ended his scholarship. With no funds available for school he had to leave USC. His coach who had been giving Tom Mix tickets to USC games asked Mix and director John Ford to give Wayne a job as a prop boy and extra. Wayne quickly started appearing as an extra in many films. He also met Wyatt Earp who was friends with Mix. Wayne would later credit Earp for giving his walk, talk and persona.

In 1969, Wayne won the Best Actor Oscar for his role in True Grit. It would be his second time being nominated, the first came 17 years earlier.

Wayne passed away from stomach cancer at the UCLA Medical Center on June 11, 1979.

Wayne was a member of Marion McDaniel Masonic Lodge No. 56 in Tuscon, Arizona. He was a 32° Scottish Rite Mason, a member of York Rite and a member of Al Malaikah Shrine Temple in Los Angeles.

(For a more extensive bio please visit: https://www.masonrytoday.com/index.php?new_month=5&new_day=26&new_year=2015)

By 2100 there could be 4.9bn dead users on Facebook. So who controls our digital legacy after we have gone? As Black Mirror returns, we delve into the issue.

Esther Earl never meant to tweet after she died. On 25 August 2010, the 16-year-old internet vlogger died after a four-year battle with thyroid cancer. In her early teens, Esther had gained a loyal following online, where she posted about her love of Harry Potter, and her illness. Then, on 18 February 2011 – six months after her death – Esther posted a message on her Twitter account, @crazycrayon.

“It’s currently Friday, January 14 of the year 2010. just wanted to say: I seriously hope that I’m alive when this posts,” she wrote, adding an emoji of a smiling face in sunglasses. Her mother, Lori Earl from Massachusetts, tells me Esther’s online friends were “freaked out” by the tweet.

“I’d say they found her tweet jarring because it was unexpected,” she says. Earl doesn’t know which service her daughter used to schedule the tweet a year in advance, but believes it was intended for herself, not for loved ones after her death. “She hoped she would receive her own messages … [it showed] her hopes and longings to still be living, to hold on to life.”

Although Esther did not intend her tweet to be a posthumous message for her family, a host of services now encourage people to plan their online afterlives. Want to post on social media and communicate with your friends after death? There are lots of apps for that! Replika and Eternime are artificially intelligent chatbots that can imitate your speech for loved ones after you die; GoneNotGone enables you to send emails from the grave; and DeadSocial’s “goodbye tool” allows you to “tell your friends and family that you have died”. In season two, episode one of Black Mirror, a young woman recreates her dead boyfriend as an artificial intelligence – what was once the subject of a dystopian 44-minute fantasy is nearing reality.

“We should think really carefully about anything we’re entrusting or storing on any digital platform,” says Dr Elaine Kasket, a psychologist and author of All the Ghosts in the Machine: Illusions of Immortality in the Digital Age. “If our digital stuff were like our material stuff, we would all look like extreme hoarders.” Kasket says it is naive to assume that our online lives die with us. In practice, your hoard of digital data can cause endless complications for loved ones, particularly when they don’t have access to your passwords.

“I cursed my father every step of the way,” says Richard, a 34-year-old engineer from Ontario who was made executor of his father’s estate four years ago. Although Richard’s father left him a list of passwords, not one remained valid by the time of his death. Richard couldn’t access his father’s online government accounts, his email (to inform his contacts about the funeral), or even log on to his computer. For privacy reasons, Microsoft refused to help Richard access his father’s computer. “Because of that experience I will never call Microsoft again,” he says.

Compare this with the experience of Jan-Ole Lincke, a 24-year-old pharmaceutical worker from Hamburg whose father left up-to-date passwords behind on a sheet of paper when he died two years ago. “Getting access was thankfully very easy,” says Lincke, who was able to download pictures from his father’s Google profile, shut down his email to prevent hacking, and delete credit card details from his Amazon account. “It definitely made me think about my own [digital legacy],” says Lincke, who has now written his passwords down.

Yet despite growing awareness about the data we leave behind, very few of us are doing anything about it. In 2013, a Brighton-based company called Cirrus Legacy made headlines after it began allowing people to securely leave behind passwords for a nominated loved one. Yet the Cirrus website is now defunct, and the Guardian was unable to reach its founder for comment. Clarkson Wright & Jakes Solicitors, a Kent-based law firm that offered the Cirrus service to its clients, says the option was never popular.

“We’ve been aware for quite a period now that the big issue for the next generation is digital footprints,” says Jeremy Wilson, head of the wills and estates team at CWJ. “Cirrus made sense and ticked a lot of boxes but, to be honest, not one client has taken us up on it.”

Wilson also notes that people don’t know about the laws surrounding digital assets such as the music, movies and games they have downloaded. While many of us assume we own our iTunes library or collection of PlayStation games, in fact, most digital downloads are only licensed to us, and this licence ends when we die.

What we want to do and what the law allows us to do with our digital legacy can therefore be very different things. Yet at present it is not the law that dominates our decisions about digital death. “Regulation is always really slow to keep up with technology,” says Kasket. “That means that platforms and corporations like Facebook end up writing the rules.”

In 2012, a 15-year-old German girl died after being hit by a subway train in Berlin. Although the girl had given her parents her online passwords, they were unable to access her Facebook account because it had been “memorialised” by the social network. Since October 2009, Facebook has allowed profiles to be transformed into “memorial pages” that exist in perpetuity. No one can then log into the account or update it, and it remains frozen as a place for loved ones to share their grief.

The girl’s parents sued Facebook for access to her account – they hoped to use it to determine whether her death was suicide. They originally lost the case, although a German court later granted the parents permission to get into her account, six years after her death.

“I find it concerning that any big tech company that hasn’t really shown itself to be the most honest, transparent or ethical organisation is writing the rulebook for how we should grieve, and making moral judgments about who should or shouldn’t have access to sensitive personal data,” says Kasket. The author is concerned with how Facebook uses the data of the dead for profit, arguing that living users keep their Facebook accounts because they don’t want to be “locked out of the cemetery” and lose access to relatives’ memorialised pages. As a psychologist, she is also concerned that Facebook is dictating our grief.

“Facebook created memorial profiles to prevent what they called ‘pain points’, like getting birthday reminders for a deceased person,” she says. “But one of the mothers I spoke to for my book was upset when her daughter’s profile was memorialised and she stopped getting these reminders. She was like, ‘This is my daughter, I gave birth to her, it’s still her birthday’.”

While Facebook users now have the option to appoint a “legacy contact” who can manage or delete their profile after death, Kasket is concerned that there are very few personalisation options when it comes to things like birthday reminders, or whether strangers can post on your wall. “The individuality and the idiosyncrasy of grief will flummox Facebook every time in its attempts to find a one-size-fits-all solution,” she says.

Matthew Helm, a 27-year-old technical analyst from Minnesota, says his mother’s Facebook profile compounded his grief after she died four years ago. “The first year was the most difficult,” says Helm, who felt some relatives posted about their grief on his mother’s wall in order to get attention. “In the beginning I definitely wished I could just wipe it all.” Helm hoped to delete the profile but was unable to access his mother’s account. He did not ask the tech giant to delete the profile because he didn’t want to give it his mother’s death certificate.

Conversely, Stephanie Nimmo, a 50-year-old writer from Wimbledon, embraced the chance to become her husband’s legacy contact after he died of bowel cancer in December 2015. “My husband and I shared a lot of information on Facebook. It almost became a bit of an online diary,” she says. “I didn’t want to lose that.” She is pleased people continue to post on her husband’s wall, and enjoys tagging him in posts about their children’s achievements. “I’m not being maudlin or creating a shrine, just acknowledging that their dad lived and he played a role in their lives,” she explains.

Nimmo is now passionate about encouraging people to plan their digital legacies. Her husband also left her passwords for his Reddit, Twitter, Google and online banking accounts. He also deleted Facebook messages he didn’t want his wife to see. “Even in a marriage there are certain things you wouldn’t want your other half to see because it’s private,” says Nimmo. “It worries me a little that if something happened to me, there are things I wouldn’t want my kids to see.”

When it comes to the choice between allowing relatives access to your accounts or letting a social media corporation use your data indefinitely after your death, privacy is a fundamental issue. Although the former makes us sweat, the latter is arguably more dystopian. Dr Edina Harbinja is a law lecturer at Aston University, who argues that we should all legally be entitled to postmortem privacy.

“The deceased should have the right to control what happens to their personal data and online identities when they die,” she says, explaining that the Data Protection Act 2018 defines “personal data” as relating only to living people. Harbinja says this is problematic because rules such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation don’t apply to the dead, and because there are no provisions that allow us to pass on our online data in wills. “There can be many issues because we don’t know what would happen if someone is a legacy contact on Facebook, but the next of kin want access.” For example, if you decide you want your friend to delete your Facebook pictures after you die, your husband could legally challenge this. “There could be potential court cases.”

Kasket says people “don’t realise how much preparation they need to do in order to make plans that are actually able to be carried out”. It is clear that if we don’t start making decisions about our digital deaths, then someone else will be making them for us. “What one person craves is what another person is horrified about,” says Kasket.

Esther Earl continued to tweet for another year after her death. Automated posts from the music website Last.fm updated her followers about the music she enjoyed. There is no way to predict the problems we will leave online when we die; Lori Earl would never have thought of revoking Last.fm’s permissions to post on her daughter’s page before she died. “We would have turned off the posts if we had been able to,” she says.

Kasket says “the fundamental message” is to think about how much you store digitally. “Our devices, without us even having to try, capture so much stuff,” she says. “We don’t think about the consequences for when we’re not here any more.”

• Black Mirror season 5 launches on Netflix on 5 June.

(For the source of this, and many other quite interesting articles, please visit: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/jun/02/digital-legacy-control-online-identities-when-we-die/)

Why people become vegans: The history, sex and science of a meatless existence

Disclosure statement

Joshua T. Beck does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Oregon provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

At the age of 14, a young Donald Watson watched as a terrified pig was slaughtered on his family farm. In the British boy’s eyes, the screaming pig was being murdered. Watson stopped eating meat and eventually gave up dairy as well.

Later, as an adult in 1944, Watson realized that other people shared his interest in a plant-only diet. And thus veganism – a term he coined – was born.

Flash-forward to today, and Watson’s legacy ripples through our culture. Even though only 3 percent of Americans actually identify as vegan, most people seem to have an unusually strong opinion about these fringe foodies – one way or the other.

As a behavioral scientist with a strong interest in consumer food movements, I thought November – World Vegan Month – would be a good time to explore why people become vegans, why they can inspire so much irritation and why many of us meat-eaters may soon join their ranks.

It’s an ideology not a choice

Like other alternative food movements such as locavorism, veganism arises from a belief structure that guides daily eating decisions.

They aren’t simply moral high-grounders. Vegans do believe it’s moral to avoid animal products, but they also believe it’s healthier and better for the environment.

Also, just like Donald Watson’s story, veganism is rooted in early life experiences.

Psychologists recently discovered that having a larger variety of pets as a child increases tendencies to avoid eating meat as an adult. Growing up with different sorts of pets increases concern for how animals are treated more generally.

Thus, when a friend opts for Tofurky this holiday season, rather than one of the 45 million turkeys consumed for Thanksgiving, his decision isn’t just a high-minded choice. It arises from beliefs that are deeply held and hard to change.

Veganism as a symbolic threat

That doesn’t mean your faux-turkey loving friend won’t seem annoying if you’re a meat-eater.

Why do some people find vegans so irritating? In fact, it might be more about “us” than them.

Most Americans think meat is an important part of a healthy diet. The government recommends eating 2-3 portions (5-6 ounces) per day of everything from bison to sea bass. As tribal humans, we naturally form biases against individuals who challenge our way of life, and because veganism runs counter to how we typically approach food, vegans feel threatening.

Humans respond to feelings of threat by derogating out-groups. Two out of 3 vegans experience discrimination daily, 1 in 4 report losing friends after “coming out” as vegan, and 1 in 10 believe being vegan cost them a job.

Veganism can be hard on a person’s sex life, too. Recent research finds that the more someone enjoys eating meat, the less likely they are to swipe right on a vegan. Also, women find men who are vegan less attractive than those who eat meat, as meat-eating seems masculine.

Crossing the vegan divide

It may be no surprise that being a vegan is tough, but meat-eaters and meat-abstainers probably have more in common than they might think.

Vegans are foremost focused on healthy eating. Six out of 10 Americans want their meals to be healthier, and research shows that plant-based diets are associated with reduced risk for heart disease, certain cancers, and Type 2 diabetes.

It may not be surprising, then, that 1 in 10 Americans are pursuing a mostly veggie diet. That number is higher among younger generations, suggesting that the long-term trend might be moving away from meat consumption.

In addition, several factors will make meat more costly in the near future.

Meat production accounts for as much as 15 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, and clear-cutting for pasture land destroys 6.7 million acres of tropical forest per year. While some debate exists on the actual figures, it is clear that meat emits more than plants, and population growth is increasing demand for quality protein.

Seizing the opportunity, scientists have innovated new forms of plant-based meats that have proven to be appealing even to meat-eaters. The distributor of Beyond Meat’s plant-based patties says 86 percent of its customers are meat-eaters. It is rumored that this California-based vegan company will soon be publicly traded on Wall Street.

Even more astonishing, the science behind lab-grown, “cultured tissue” meat is improving. It used to cost more than $250,000 to produce a single lab-grown hamburger patty. Technological improvements by Dutch company Mosa Meat have reduced the cost to $10 per burger.

Watson’s legacy

Even during the holiday season, when meats like turkey and ham take center stage at family feasts, there’s a growing push to promote meatless eating.

London, for example, will host its first-ever “zero waste” Christmas market this year featuring vegan food vendors. Donald Watson, who was born just four hours north of London, would be proud.

Watson, who died in 2006 at the ripe old age of 95, outlived most of his critics. This may give quiet resolve to vegans as they brave our meat-loving world.

(For the source of this, and many other interesting articles, please visit: https://theconversation.com/why-people-become-vegans-the-history-sex-and-science-of-a-meatless-existence-106410/)

Did human ancestors split from chimps in Europe, not Africa?

It’s generally accepted that humans originated in Africa and gradually spread out across the globe from there, but a pair of new studies may paint a different picture. By examining fossils of early hominins, researchers have found that humans and chimpanzees may have split from their last common ancestor earlier than previously thought, and this important event may have happened in the ancient savannahs of Europe, not Africa.

The split between humans and our closest living relatives, chimpanzees, is a murky area in our history. While the point of original divergence is thought to have been between 5 and 7 million years ago, it wasn’t a clean break, and cross breeding and hybridization may have continued until as recently as 4 million years ago.

Where the divergence took place is contentious as well, but Eastern Africa is the accepted birthplace of the earliest pre-humans. One of the best candidates for the last common ancestor is Sahelanthropus, known from a skull found in Central Africa dating back to around 7 million years ago. But according to the new studies, bones found in Greece and Bulgaria appear to belong to a hominin that’s a few hundred thousand years older.

“Our discovery outlines a new scenario for the beginning of human history – the findings allow us to move the human-chimpanzee split into the Mediterranean area,” says David Begun, co-author of one of the studies. “These research findings call into question one of the most dogmatic assertions in paleoanthropology since Charles Darwin, which is that the human lineage originated in Africa. It is critical to know where the human lineage arose so that we can reconstruct the circumstances leading to our divergence from the common ancestor we share with chimpanzees.”

The Mediterranean bones are from a species called Graecopithecus freybergi, and it’s one of the least understood European apes. The researchers scanned a jawbone found in Greece and an upper premolar from Bulgaria, and found the roots of the teeth to be largely fused together, indicating that the species might have been an early hominin.

“While great apes typically have two or three separate and diverging roots, the roots of Graecopithecus converge and are partially fused – a feature that is characteristic of modern humans, early humans and several pre-humans including Ardipithecus and Australopithecus,” says Madelaine Böhme, co-lead investigator on the project.

To get a clearer picture, the researchers studied the sediment that the fossils were found in, and discovered that the two sites were very similar. Not only were they almost exactly the same age – 7.24 and 7.175 million years – but both areas were dry, grassy savannahs at the time, making them prime conditions for hominins.

The researchers found grains of dust that appeared to have blown up from the Sahara desert, which was forming around the same time. This might have contributed to the savannah-like conditions in Europe, and these environmental changes may have driven the two species to evolve differently.

“The incipient formation of a desert in North Africa more than seven million years ago and the spread of savannahs in Southern Europe may have played a central role in the splitting of the human and chimpanzee lineages,” says Böhme.

But inferring information from fossils always leaves room for error, and as New Scientist reports, there are researchers who aren’t convinced such big claims can be projected from such small features of the fossils. Still, it’s an interesting theory, and one that will warrant more study.

Source: University of Toronto

(For the source of this, and many other interesting articles, please visit: https://newatlas.com/fossil-human-chimp-ancestor-europe/49708/)

Ancient pee helps archaeologists track the rise of farming

One of the most important transitions in human history was when we stopped hunting and gathering for food and instead settled down to become farmers. Now, to reconstruct the history of one particular archaeological site in Turkey, scientists have examined a pretty unexpected source – the salts left behind from human and animal pee.

The dig site of Aşıklı Höyük in Turkey has been studied for decades, and it’s clear that humans occupied the area more than 10,000 years ago, where they started experimenting with keeping animals like sheep and goats. But just how many people and animals occupied the site at different times has been trickier to track.

For the new study, researchers from the Universities of Columbia, Tübingen, Arizona and Istanbul realized that the more humans and animals there are on a site, the higher the concentration of salts in the ground. The reason? Everybody and everything pees.

The team began by collecting 113 samples from across Aşıklı Höyük, including trash piles, bricks, hearths and soil, from all different time periods. They examined the levels of sodium, nitrate and chlorine salts, which are all passed in urine.

Sure enough, the fluctuating levels of urine salts revealed the history of human and animal occupation of Aşıklı Höyük. Very little salt was detected in the natural layers, before any settlement existed. Between about 10,400 and 10,000 years ago, salt levels rose slightly, as a few humans began settling. Then things really took off – between 10,000 and 9,700 years ago the salts saw a huge spike, with levels about 1,000 times higher than previously detected. That indicates a similar spike in the number of occupants. After that, concentrations go into decline again.

That large spike, the team says, suggests that domestication of animals in Aşıklı Höyük occurred faster than was previously thought.

Using this data, the researchers estimated that over the 1,000-year period of occupation, an average of 1,790 people and animals lived in the area per day. At its peak, the population density would have reached about one person or animal for every 10 sq m (108 sq ft).

The estimated inhabitants of each time period can’t be all human – the houses found on site indicate a smaller population. But the team says this is evidence that salt concentrations can be a useful tool to study the density of domesticated animals over time.

The researchers say this technique could be used in other sites, to help find new evidence of the timing and density of human settlement.

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: Columbia University

An audio version of this article is available to New Atlas Plus subscribers.

(For the source of this, and many other equally interesting articles, please visit: https://newatlas.com/urine-salts-ancient-farming/59360/)

Japan’s ‘vanishing’ Ainu will finally be recognized as indigenous people

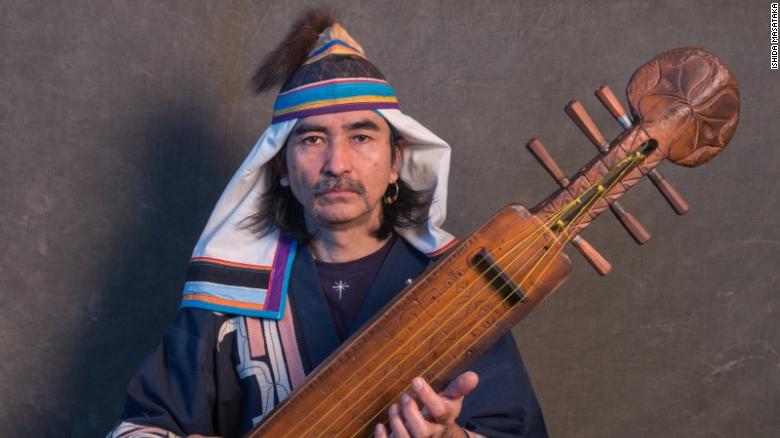

Growing up in Japan, musician Oki Kano never knew he was part of a “vanishing people.”

For decades, researchers and conservative Japanese politicians described the Ainu as “vanishing,” says Jeffry Gayman, an Ainu peoples researcher at Hokkaido University.

Gayman says there might actually be tens of thousands more people of Ainu descent who have gone uncounted — due to discrimination, many Ainu chose to hide their background and assimilate years ago, leaving younger people in the dark about their heritage.

A bill, which was passed recently, for the first time has officially recognized the Ainu of Hokkaido as an “indigenous” people of Japan. The bill also includes measures to make Japan a more inclusive society for the Ainu, strengthen their local economies and bring visibility to their culture.

Japanese land minister Keiichi Ishii told reporters that it was important for the Ainu to maintain their ethnic dignity and pass on their culture to create a vibrant and diverse society.

Yet some warn a new museum showcasing their culture risks turning the Ainu into a cultural exhibit and note the bill is missing one important thing — an apology.

‘Tree without roots’

“Bob Marley sang that people who forget about their ancestors are the same as a tree without roots,” says Kano, 62. “I checked the lyrics as a teenager, though they became more meaningful to me as I matured.”

After discovering his ethnic origins, Kano was determined to learn more. He traveled to northern Hokkaido to meet his father and immediately felt an affinity with the Ainu community there — the “Asahikawa,” who are known for their anti-establishment stance.

But his sense of belonging was short-lived — some Ainu rejected Kano for having grown up outside of the community, saying he would never fully understand the suffering they had endured under Japanese rule.

–

Yuji Shimizu, an Ainu elder, says he faced open discrimination while growing up in Hokkaido. He says other children called him a dog and bullied him for looking different.

Hoping to avoid prejudice, his parents never taught him traditional Ainu customs or even the language, says the 78-year-old former teacher.

“My mother told me to forget I was Ainu and become like the Japanese if I wanted to be successful,” says Shimizu.

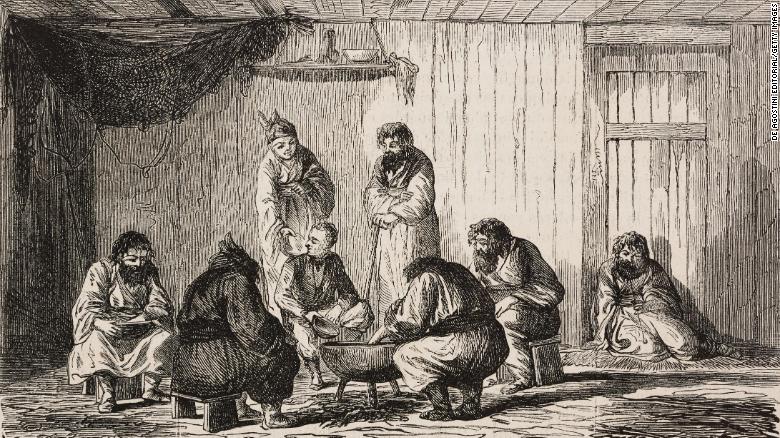

Ainu Moshir (Land of the Ainu)

They were early residents of northern Japan, in what is now the Hokkaido prefecture, and the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin, off the east coast of Russia. They revered bears and wolves, and worshiped gods embodied in the natural elements like water, fire and wind.

In the 15th century, the Japanese moved into territories held by various Ainu groups to trade. But conflicts soon erupted, with many battles fought between 1457 and 1789. After the 1789 Battle of Kunasiri-Menasi, the Japanese conquered the Ainu.

Japan’s modernization in the mid-1800s was accompanied by a growing sense of nationalism and, in 1899, the government sought to assimilate the Ainu by introducing the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act.

The act implemented Japan’s compulsory national education system in Hokkaido and eliminated traditional systems of Ainu land rights and claims. Over time, the Ainu were forced to give up their land and adopt Japanese customs through a series of government initiatives.

Today, there are only two native Ainu speakers worldwide, according to the Endangered Languages Project, a organization of indigenous groups and researchers aimed at protecting endangered languages.

High levels of poverty and unemployment currently hinder the Ainu’s social progress. The percentage of Ainu who attend high school and university is far lower than the Hokkaido average.

The Ainu population also appears to have shrunk. Official figures put the number of Ainu in Hokkaido at 17,000 in 2013, accounting for around 2% of the prefecture’s population. In 2017, the latest year on record, there were only about 13,000.

However, Gayman, the Ainu researcher, says that the number of Ainu could be up to ten times higher than official surveys suggest, because many have chosen not to identify as Ainu and others have forgotten — or never known — their origins.

Finding music

While living there, he befriended several Native Americans at a time when indigenous peoples were putting pressure on governments globally to recognize their rights. He credits them with awakening his political conscience as a member of the Ainu.

“I knew I had to reconnect with my Ainu heritage,” he says. Kano made his way back to Japan and, in 1993, discovered a five-stringed instrument called the “tonkori,” once considered a a symbol of Ainu culture.

“I made a few songs with the tonkori and thought I had talent,” he says, despite never having formally studied music. But finding a tonkori master to teach him was hard after years of cultural erasure.

So he used old cassette tapes of Ainu music as a reference. “It was like when you copy Jimi Hendrix while learning how to play the guitar,” he says.

His persistence paid off. In 2005, Kano created the Oki Dub Ainu group, which fuses Ainu influence with reggae, electronica and folk undertones. He also created his own record label to introduce Ainu music to the world.

Since then, Kano has performed in Australia and toured Europe. He has also taken part in the United Nation’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations to voice Ainu concerns.

–

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

The United Nations adopted UNDRIP on September 13, 2007, to enshrine the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.”

The UNDRIP protects collective rights that may not feature in other human rights charters. It emphasizes individual rights, and also safeguards the individual rights of Indigenous people.

New law, new future?

Winchester and Gayman also say the government failed to consult all Ainu groups when drafting the bill.

For the Ainu elder Shimizu, the new bill is missing an important part: atonement. “Why doesn’t the government apologize? If the Japanese recognized what they did in the past, I think we could move forward,” says Shimizu.

“The Japanese forcibly colonized us and annihilated our culture. Without even admitting to this, they want to turn us into a museum exhibit,” Shimizu adds, referring to the 2019 bill’s provision to open an Ainu culture museum in Hokkaido.

–

Other Ainu say the museum will create jobs.

Currently, Ainu youth are eligible for scholarships and grants to study their own language and culture at a few select private universities. But Kano says government funding should extend beyond supporting Ainu heritage, to support the Ainu people.

–

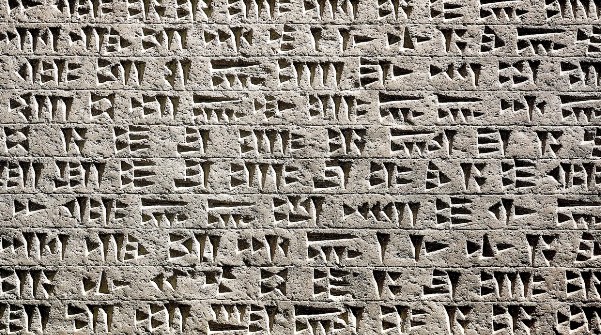

Unrelated Languages Often Use Same Sounds for Common Objects and Ideas, Research Finds

A careful statistical examination of words from 6,000+ languages shows that humans tend to use the same sounds for common objects and ideas, no matter what language they’re speaking.

Geographic distribution of the 6,452 word lists analyzed in this study. Colors distinguish different linguistic macroareas, regions with relatively little or no contact between them (but with much internal contact between their populations). These are North America (orange), South America (dark green), Eurasia (blue), Africa (green), Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands (red), and Australia (fuchsia). Image credit: Damián E. Blasi et al.

The new research, led by Prof. Morten Christiansen of Cornell University, demonstrates a robust statistical relationship between certain basic concepts – from body parts to familial relationships and aspects of the natural world – and the sounds humans around the world use to describe them.

“These sound symbolic patterns show up again and again across the world, independent of the geographical dispersal of humans and independent of language lineage,” Prof. Christiansen said.

“There does seem to be something about the human condition that leads to these patterns. We don’t know what it is, but we know it’s there.”

Prof. Christiansen and his colleagues from Argentina, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland analyzed 40-100 basic vocabulary words in 62% of the world’s more than 6,000 current languages and 85 percent of its linguistic lineages.

“The dataset used for this study is drawn from version 16 of the Automated Similarity Judgment Program database,” they explained.

“The data consist of 28–40 lexical items from 6,452 word lists, with a subset of 328 word lists having up to 100 items. The word lists include both languages and dialects, spanning 62% of the world’s languages and about 85% of its lineages.”

The words included pronouns, body parts and properties (small, full), verbs that describe motion and nouns that describe natural phenomena (star, fish).

The scientists found a considerable proportion of the 100 basic vocabulary words have a strong association with specific kinds of human speech sounds.

For instance, in most languages, the word for ‘nose’ is likely to include the sounds ‘neh’ or the ‘oo’ sound, as in ‘ooze.’

The word for ‘tongue’ is likely to have ‘l’ or ‘u.’

‘Leaf’ is likely to include the sounds ‘b,’ ‘p’ or ‘l.’

‘Sand’ will probably use the sound ‘s.’

The words for ‘red’ and ‘round’ often appear with ‘r,’ and ‘small’ with ‘i.’

“It doesn’t mean all words have these sounds, but the relationship is much stronger than we’d expect by chance. The associations were particularly strong for words that described body parts. We didn’t quite expect that,” Prof. Christiansen said.

The researchers also found certain words are likely to avoid certain sounds. This was especially true for pronouns.

For example, words for ‘I’ are unlikely to include sounds involving u, p, b, t, s, r and l.

‘You’ is unlikely to include sounds involving u, o, p, t, d, q, s, r and l.

The team’s findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, challenge one of the most basic concepts in linguistics: the century-old idea that the relationship between a sound of a word and its meaning is arbitrary.

The researchers don’t know why humans tend to use the same sounds across languages to describe basic objects and ideas.

“These concepts are important in all languages, and children are likely to learn these words early in life,” Prof. Christiansen said.

“Perhaps these signals help to nudge kids into acquiring language.”

“Likely it has something to do with the human mind or brain, our ways of interacting, or signals we use when we learn or process language. That’s a key question for future research.”

_____

Damián E. Blasi et al. Sound–meaning association biases evidenced across thousands of languages. PNAS, published online September 12, 2016; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605782113

(For the source of this, and many other interesting articles, please visit: www.sci-news.com/othersciences/linguistics/languages-use-same-sounds-common-objects-ideas-04185.html/)

Neanderthals, Denisovans May Have Had Their Own Language, Suggest Scientists

A broad range of evidence from linguistics, genetics, paleontology, and archaeology suggests that Neanderthals and Denisovans shared with us something like modern speech and language, according to Dutch psycholinguistics researchers Dr Dan Dediu and Dr Stephen Levinson.

Neanderthals have fascinated both the academic world and the general public ever since their discovery almost 200 years ago. Initially thought to be subhuman brutes incapable of anything but the most primitive of grunts, they were a successful form of humanity inhabiting vast swathes of western Eurasia for several hundreds of millennia, during harsh ages and milder interglacial periods.

Scientists knew that Neanderthals were our closest cousins, sharing a common ancestor with us, probably Homo heidelbergensis, but it was unclear what their cognitive capacities were like, or why modern humans succeeded in replacing them after thousands of years of cohabitation.

Due to new discoveries and the reassessment of older data, but especially to the availability of ancient DNA, researchers have started to realize that Neanderthals’ fate was much more intertwined with ours and that, far from being slow brutes, their cognitive capacities and culture were comparable to ours.

Dr Dediu and Dr Levinson, both from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics and the Radboud University Nijmegen, reviewed all these strands of literature, and argue that essentially modern language and speech are an ancient feature of our lineage dating back at least to the most recent ancestor we shared with the Neanderthals and the Denisovans. Their interpretation of the intrinsically ambiguous and scant evidence goes against the scenario usually assumed by most language scientists.

The study, reported in the journal Frontiers in Language Sciences, pushes back the origins of modern language by a factor of ten – from the often-cited 50,000 years to 500,000 – 1,000,000 years ago – somewhere between the origins of our genus, Homo, some 1.8 million years ago, and the emergence of Homo heidelbergensis.

This reassessment of the evidence goes against a scenario where a single catastrophic mutation in a single individual would suddenly give rise to language, and suggests that a gradual accumulation of biological and cultural innovations is much more plausible.

Interestingly, given that we know from the archaeological record and recent genetic data that the modern humans spreading out of Africa interacted both genetically and culturally with the Neanderthals and Denisovans, then just as our bodies carry around some of their genes, maybe our languages preserve traces of their languages too.

This would mean that at least some of the observed linguistic diversity is due to these ancient encounters, an idea testable by comparing the structural properties of the African and non-African languages, and by detailed computer simulations of language spread.

______

Bibliographic information: Dediu D and Levinson SC. 2013. On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neanderthal linguistic capacities and its consequences. Front. Psychol. 4: 397; doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397

(For the source of this, and other equally important articles, please visit: http://www.sci-news.com/othersciences/linguistics/science-neanderthals-denisovans-language-01211.html/)

A Mysterious Third Human Species Lived Alongside Neanderthals in This Cave

It’s a “fascinating part of human history.”

Scientists digging in the mountains of southern Siberia have revealed key insights into the lives of Denisovans, a mysterious branch of the ancient human family tree. While these relatives are extinct, their legacy lives on in the modern humans who carry fragments of their DNA and in the tiny artifacts and bones they left behind. Compared to the well-known Neanderthals, there’s a lot we don’t know about the Denisovans — but a pair of papers published recently hint at their place in our shared history.

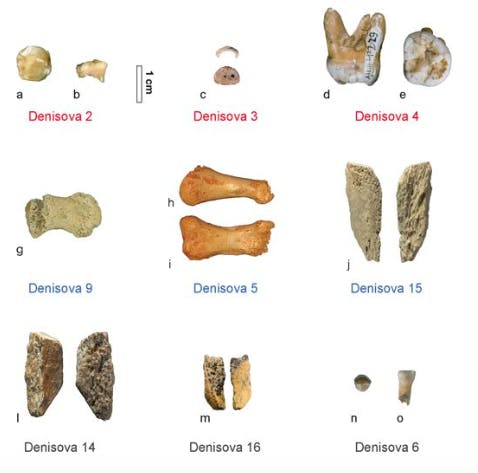

Both Neanderthals and Denisovans belong to the genus Homo, though it’s still not entirely clear whether the Denisovans are a separate species or a subspecies of modern humans — after all, we only have six fossil fragments to go on. Nevertheless, we’re one step closer to finding out. Both studies, published in Nature, describe new discoveries in the Denisova Cave of the Altai Mountains, where excavations have continued for the past 40 years. Those efforts have revealed ancient human remains carrying the DNA of both the Denisovans and Neanderthals who made the high-ceilinged cave their home — sometimes, even having children together.

For a long time, nobody knew exactly how long this cave was occupied and the nature of the interactions of the hominins living there. But now, the studies collectively reveal that humans occupied the cave from approximately 200,000 years ago to 50,000 years ago.

The authors of one study focused on Denisovan fossils and artifacts to determine “aspects of their cultural and subsistence adaptions.” Katerina Douka, Ph.D., the co-author of that study and a researcher at Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, tells Inverse that confirming that they lived in this cave is a “fascinating part of human history.” However, she adds, we still don’t know so much about the Denisovans — not their geographic range, their location of origin, or even what they looked like.

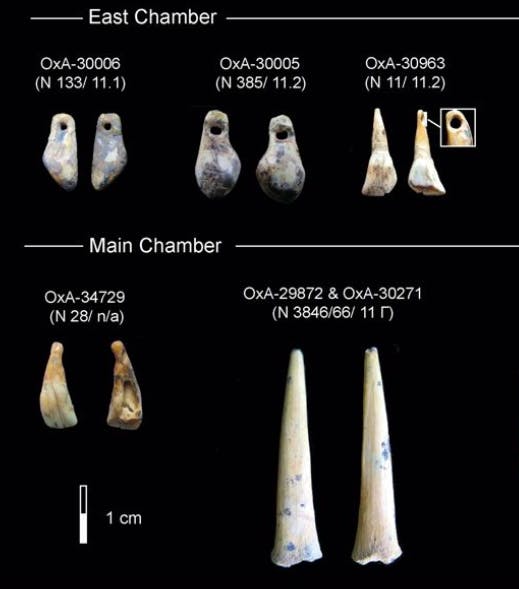

When they lived in the cave, and with whom, is another mystery about the Denisovans that was investigated, sediment layer by sediment layer, in the second study. Published by scientists from the University of Wollongong and the Russian Academy of Sciences, the analysis is the most comprehensive dating project ever done on the Denisova Cave deposits. The team dated 103 sediment layers and 50 items within them, mostly bits of bone, charcoal, and tools. The oldest Denisovan DNA comes from a layer between 185,000 and 217,000 years old, and the oldest Neanderthal DNA sample is from a layer that’s about 172,000 to 205,000 years old. In the more recent layers of the cave, between 55,200 to 84,100 years old, only Denisovan remains were found.

And it’s in these more recent years where more advanced objects begin to emerge — pieces of tooth pendants and bone points, which “may be assumed” as “associated with the Denisovan population,” write Douka and her team. Those artifacts are the oldest of their kind found in northern Eurasia and representative of something previously unexplored: Denisovan culture.

At this point, says Douka, we cannot definitively say that Denisovans created those items, though the evidence is pointing that way. More sites with Denisovan remains and material culture are needed to answer deeper questions about their culture and symbols.

April Nowell, Ph.D. is a University of Victoria professor and Paleolithic archeologist who specializes in the origins of art and symbol use and wasn’t a part of these recent papers. Evaluating the pendants and bones, she tells Inverse that, assuming these artifacts were made by the Denisovans, she’s “not particularly surprised.” Human culture, very broadly, is thought to have emerged 3.3 million years ago, with the first stone tools. Other ancient humans used the natural clay ochre to paint at least 100,000 years ago, the same time period where archeologists have found the oldest beads.

So, it makes sense that a human subspecies would create cultural artifacts around this time.

What’s novel in the new studies, Nowell says, is that “we know virtually nothing about who Denisovans were, so every study like this one helps to enrich our understanding of their place in the human story.”

“Given that we have items of personal adornment associated with Neanderthals and modern humans all around the same date as the ones thought to be associated with the Denisovans,” she adds, “I would find it more surprising if they were not making similar objects.”

These particular items, Nowell explains, especially the tooth pendant, likely speak to “issues of personal identity and group belonging.” The teeth were purposefully chosen, modified, and worn — standing as jewelry that communicates something about both the wearer and likely influenced how the wearer felt about themselves.

Jewelry, she says, can be powerful and laden with meaning — just think about putting on a wedding ring or holding your grandfather’s pocket watch. We can’t tell what these pendants meant to the Denisovans who created and wore them, but their very existence allows archeologists to begin to piece together an idea of the culture from which they were wrought.

(For the source of this, and many additional interesting articles, please visit: https://www.inverse.com/article/52926-denisova-cave-dating-sediment-culture/)

New species of human discovered in cave in Philippines

A new species of human has been discovered in a cave in the Philippines. Named Homo luzonensis after the island of Luzon where it was found, the hominin appears to have lived over 50,000 years ago, painting a more complete picture of human evolution.

The new species is known from 12 bones found in Callao Cave, which are thought to be the remains of at least two adults and a juvenile. This includes several finger and toe bones, some teeth and a partial femur. While that might not sound like much to work with, scientists can use that to determine more than you might expect.

“There are some really interesting features – for example, the teeth are really small,” says Professor Philip Piper, co-author of the study. “The size of the teeth generally, though not always, reflect the overall body-size of a mammal, so we think Homo luzonensis was probably relatively small. Exactly how small we don’t know yet. We would need to find some skeletal elements from which we could measure body-size more precisely.”

Even with those scattered bones, scientists are able to start slotting Homo luzonensis into the hominin family tree. Although it is a distinct species of its own, it does share different traits with many of its relatives, including Neanderthals, modern humans, and most notably Homo floresiensis – the “Hobbit” humans discovered in an Indonesian cave in 2003. But perhaps the strangest family resemblance is to the Australopithecus, a far more ancient ancestor of ours.

“It’s quite incredible, the hand and feet bones are remarkably Australopithecine-like,” says Piper. “The Australopithecines last walked the Earth in Africa about 2 million years ago and are considered to be the ancestors of the Homo group, which includes modern humans. So, the question is whether some of these features evolved as adaptations to island life, or whether they are anatomical traits passed down to Homo luzonensis from their ancestors over the preceding 2 million years.”

The research was published in the journal Nature.

An audio version of this article is available to New Atlas Plus subscribers.

(For the source of this very interesting articles, plus many others, please visit: https://newatlas.com/new-human-species-homo-luzonensis/59207/)

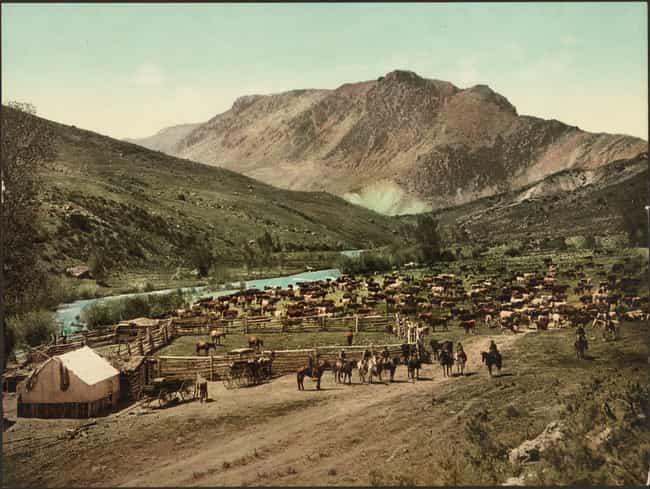

In contrast to much of what Hollywood has constructed, the real cowboy lifestyle was far less glamorous and happy than you may think. Of course, there were some smiling faces among 19th century cowboys, but the gunslinging frontier hero you may picture is a Wild West myth.

Cowboys in the old American West worked cattle drives and on ranches alike, master horsemen from all walks of life that dedicated themselves to the herd. Cowboy life in the 1800s was full of hard work, danger, and monotonous tasks with a heaping helping of dust, bugs, and beans on the side.

Cowboys Didn’t Get A Lot Of Sleep

A cowboy’s day and night revolved around the herd, a constant routine of guarding, wrangling, and caring for cattle. When cowboys were out with a herd or simply working on a ranch, they had to be on watch. With a typical watch lasting two to four hours, there was usually a rotation of men. This gave cowboys the chance to sleep for relatively short spurts, often getting six hours of sleep at the most.