–

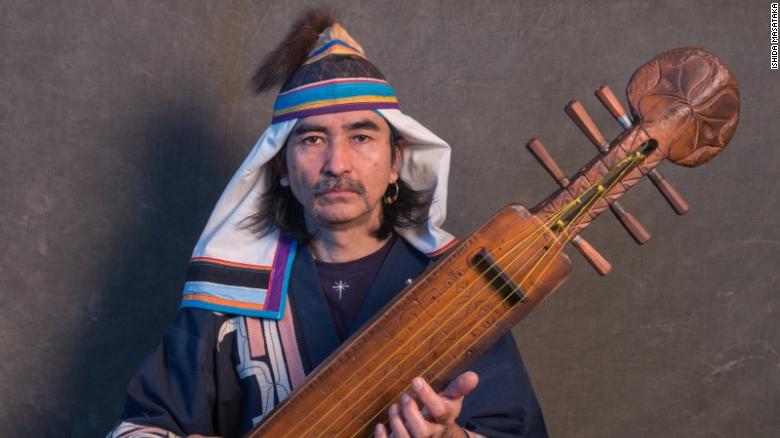

Growing up in Japan, musician Oki Kano never knew he was part of a “vanishing people.”

His Japanese mother was divorced and never told Kano that his birth father was an indigenous Ainu man. Kano was 20 years old when he found out.

–

For decades, researchers and conservative Japanese politicians described the Ainu as “vanishing,” says Jeffry Gayman, an Ainu peoples researcher at Hokkaido University.

For decades, researchers and conservative Japanese politicians described the Ainu as “vanishing,” says Jeffry Gayman, an Ainu peoples researcher at Hokkaido University.

–

Gayman says there might actually be tens of thousands more people of Ainu descent who have gone uncounted — due to discrimination, many Ainu chose to hide their background and assimilate years ago, leaving younger people in the dark about their heritage.

Gayman says there might actually be tens of thousands more people of Ainu descent who have gone uncounted — due to discrimination, many Ainu chose to hide their background and assimilate years ago, leaving younger people in the dark about their heritage.

–

Traditional Ainu Settlement Area.

–

A bill, which was passed recently, for the first time has officially recognized the Ainu of Hokkaido as an “indigenous” people of Japan. The bill also includes measures to make Japan a more inclusive society for the Ainu, strengthen their local economies and bring visibility to their culture.

A bill, which was passed recently, for the first time has officially recognized the Ainu of Hokkaido as an “indigenous” people of Japan. The bill also includes measures to make Japan a more inclusive society for the Ainu, strengthen their local economies and bring visibility to their culture.

–

Japanese land minister Keiichi Ishii told reporters that it was important for the Ainu to maintain their ethnic dignity and pass on their culture to create a vibrant and diverse society.

Japanese land minister Keiichi Ishii told reporters that it was important for the Ainu to maintain their ethnic dignity and pass on their culture to create a vibrant and diverse society.

–

Yet some warn a new museum showcasing their culture risks turning the Ainu into a cultural exhibit and note the bill is missing one important thing — an apology.

Yet some warn a new museum showcasing their culture risks turning the Ainu into a cultural exhibit and note the bill is missing one important thing — an apology.

‘Tree without roots’

Kano grew up in Kanagawa prefecture near Tokyo, where he became fascinated with Jamaican reggae. Even without being aware of his ethnic identity, the political commentary underpinning the songs made an impression on him.

–

“Bob Marley sang that people who forget about their ancestors are the same as a tree without roots,” says Kano, 62. “I checked the lyrics as a teenager, though they became more meaningful to me as I matured.”

“Bob Marley sang that people who forget about their ancestors are the same as a tree without roots,” says Kano, 62. “I checked the lyrics as a teenager, though they became more meaningful to me as I matured.”

–

After discovering his ethnic origins, Kano was determined to learn more. He traveled to northern Hokkaido to meet his father and immediately felt an affinity with the Ainu community there — the “Asahikawa,” who are known for their anti-establishment stance.

After discovering his ethnic origins, Kano was determined to learn more. He traveled to northern Hokkaido to meet his father and immediately felt an affinity with the Ainu community there — the “Asahikawa,” who are known for their anti-establishment stance.

–

But his sense of belonging was short-lived — some Ainu rejected Kano for having grown up outside of the community, saying he would never fully understand the suffering they had endured under Japanese rule.

–

But his sense of belonging was short-lived — some Ainu rejected Kano for having grown up outside of the community, saying he would never fully understand the suffering they had endured under Japanese rule.

–

–

Yuji Shimizu, an Ainu elder, says he faced open discrimination while growing up in Hokkaido. He says other children called him a dog and bullied him for looking different.

Yuji Shimizu, an Ainu elder, says he faced open discrimination while growing up in Hokkaido. He says other children called him a dog and bullied him for looking different.

–

Hoping to avoid prejudice, his parents never taught him traditional Ainu customs or even the language, says the 78-year-old former teacher.

Hoping to avoid prejudice, his parents never taught him traditional Ainu customs or even the language, says the 78-year-old former teacher.

–

“My mother told me to forget I was Ainu and become like the Japanese if I wanted to be successful,” says Shimizu.

“My mother told me to forget I was Ainu and become like the Japanese if I wanted to be successful,” says Shimizu.

Ainu Moshir (Land of the Ainu)

The origins of the Ainu and their language remain unclear, though many theories exist.

–

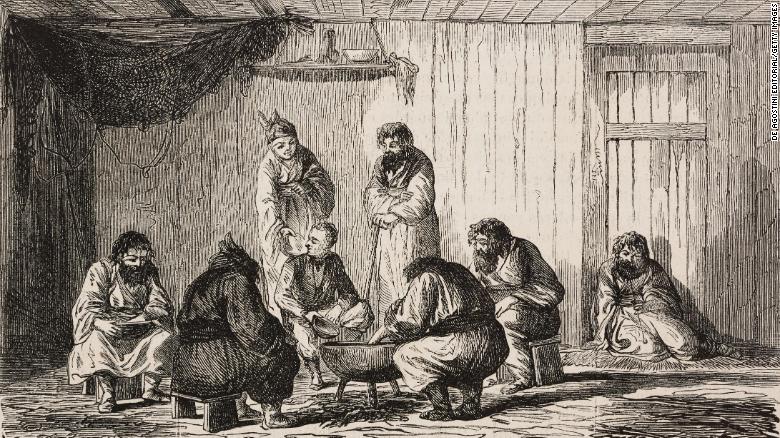

They were early residents of northern Japan, in what is now the Hokkaido prefecture, and the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin, off the east coast of Russia. They revered bears and wolves, and worshiped gods embodied in the natural elements like water, fire and wind.

They were early residents of northern Japan, in what is now the Hokkaido prefecture, and the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin, off the east coast of Russia. They revered bears and wolves, and worshiped gods embodied in the natural elements like water, fire and wind.

–

In the 15th century, the Japanese moved into territories held by various Ainu groups to trade. But conflicts soon erupted, with many battles fought between 1457 and 1789. After the 1789 Battle of Kunasiri-Menasi, the Japanese conquered the Ainu.

In the 15th century, the Japanese moved into territories held by various Ainu groups to trade. But conflicts soon erupted, with many battles fought between 1457 and 1789. After the 1789 Battle of Kunasiri-Menasi, the Japanese conquered the Ainu.

–

Japan’s modernization in the mid-1800s was accompanied by a growing sense of nationalism and, in 1899, the government sought to assimilate the Ainu by introducing the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act.

Japan’s modernization in the mid-1800s was accompanied by a growing sense of nationalism and, in 1899, the government sought to assimilate the Ainu by introducing the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act.

–

–

The act implemented Japan’s compulsory national education system in Hokkaido and eliminated traditional systems of Ainu land rights and claims. Over time, the Ainu were forced to give up their land and adopt Japanese customs through a series of government initiatives.

The act implemented Japan’s compulsory national education system in Hokkaido and eliminated traditional systems of Ainu land rights and claims. Over time, the Ainu were forced to give up their land and adopt Japanese customs through a series of government initiatives.

–

Today, there are only two native Ainu speakers worldwide, according to the Endangered Languages Project, a organization of indigenous groups and researchers aimed at protecting endangered languages.

Today, there are only two native Ainu speakers worldwide, according to the Endangered Languages Project, a organization of indigenous groups and researchers aimed at protecting endangered languages.

–

High levels of poverty and unemployment currently hinder the Ainu’s social progress. The percentage of Ainu who attend high school and university is far lower than the Hokkaido average.

High levels of poverty and unemployment currently hinder the Ainu’s social progress. The percentage of Ainu who attend high school and university is far lower than the Hokkaido average.

–

The Ainu population also appears to have shrunk. Official figures put the number of Ainu in Hokkaido at 17,000 in 2013, accounting for around 2% of the prefecture’s population. In 2017, the latest year on record, there were only about 13,000.

The Ainu population also appears to have shrunk. Official figures put the number of Ainu in Hokkaido at 17,000 in 2013, accounting for around 2% of the prefecture’s population. In 2017, the latest year on record, there were only about 13,000.

–

However, Gayman, the Ainu researcher, says that the number of Ainu could be up to ten times higher than official surveys suggest, because many have chosen not to identify as Ainu and others have forgotten — or never known — their origins.

However, Gayman, the Ainu researcher, says that the number of Ainu could be up to ten times higher than official surveys suggest, because many have chosen not to identify as Ainu and others have forgotten — or never known — their origins.

Finding music

Feeling neither Ainu nor Japanese, Kano left Japan in the late 1980s for New York.

–

While living there, he befriended several Native Americans at a time when indigenous peoples were putting pressure on governments globally to recognize their rights. He credits them with awakening his political conscience as a member of the Ainu.

While living there, he befriended several Native Americans at a time when indigenous peoples were putting pressure on governments globally to recognize their rights. He credits them with awakening his political conscience as a member of the Ainu.

–

“I knew I had to reconnect with my Ainu heritage,” he says. Kano made his way back to Japan and, in 1993, discovered a five-stringed instrument called the “tonkori,” once considered a a symbol of Ainu culture.

“I knew I had to reconnect with my Ainu heritage,” he says. Kano made his way back to Japan and, in 1993, discovered a five-stringed instrument called the “tonkori,” once considered a a symbol of Ainu culture.

–

“I made a few songs with the tonkori and thought I had talent,” he says, despite never having formally studied music. But finding a tonkori master to teach him was hard after years of cultural erasure.

“I made a few songs with the tonkori and thought I had talent,” he says, despite never having formally studied music. But finding a tonkori master to teach him was hard after years of cultural erasure.

–

So he used old cassette tapes of Ainu music as a reference. “It was like when you copy Jimi Hendrix while learning how to play the guitar,” he says.

So he used old cassette tapes of Ainu music as a reference. “It was like when you copy Jimi Hendrix while learning how to play the guitar,” he says.

–

His persistence paid off. In 2005, Kano created the Oki Dub Ainu group, which fuses Ainu influence with reggae, electronica and folk undertones. He also created his own record label to introduce Ainu music to the world.

His persistence paid off. In 2005, Kano created the Oki Dub Ainu group, which fuses Ainu influence with reggae, electronica and folk undertones. He also created his own record label to introduce Ainu music to the world.

–

Since then, Kano has performed in Australia and toured Europe. He has also taken part in the United Nation’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations to voice Ainu concerns.

Since then, Kano has performed in Australia and toured Europe. He has also taken part in the United Nation’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations to voice Ainu concerns.

–

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

The United Nations adopted UNDRIP on September 13, 2007, to enshrine the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.”

The UNDRIP protects collective rights that may not feature in other human rights charters. It emphasizes individual rights, and also safeguards the individual rights of Indigenous people.

New law, new future?

Mark John Winchester, a Japan-based indigenous rights expert, calls the new bill a “small step forward” in terms of indigenous recognition and anti-discrimination, but says it falls short of truly empowering the Ainu people. “Self-determination, which should be the central pillar of indigenous policy-making, is not reflected in the law,” says Winchester.

–

Winchester and Gayman also say the government failed to consult all Ainu groups when drafting the bill.

Winchester and Gayman also say the government failed to consult all Ainu groups when drafting the bill.

–

For the Ainu elder Shimizu, the new bill is missing an important part: atonement. “Why doesn’t the government apologize? If the Japanese recognized what they did in the past, I think we could move forward,” says Shimizu.

For the Ainu elder Shimizu, the new bill is missing an important part: atonement. “Why doesn’t the government apologize? If the Japanese recognized what they did in the past, I think we could move forward,” says Shimizu.

–

“The Japanese forcibly colonized us and annihilated our culture. Without even admitting to this, they want to turn us into a museum exhibit,” Shimizu adds, referring to the 2019 bill’s provision to open an Ainu culture museum in Hokkaido.

–

“The Japanese forcibly colonized us and annihilated our culture. Without even admitting to this, they want to turn us into a museum exhibit,” Shimizu adds, referring to the 2019 bill’s provision to open an Ainu culture museum in Hokkaido.

–

Other Ainu say the museum will create jobs.

–

–

Both Shimizu and Kano say the new law grants too much power to Japan’s central government, which requires Ainu groups to seek its approval for state-sponsored cultural projects. Furthermore, they say the bill should do more to promote education.

–

Currently, Ainu youth are eligible for scholarships and grants to study their own language and culture at a few select private universities. But Kano says government funding should extend beyond supporting Ainu heritage, to support the Ainu people.

Currently, Ainu youth are eligible for scholarships and grants to study their own language and culture at a few select private universities. But Kano says government funding should extend beyond supporting Ainu heritage, to support the Ainu people.

–

“We need more Ainu to enter higher education and become Ainu lawyers, film directors and professors,” he says. “If that doesn’t happen, the Japanese will always control our culture.”

–