Most visitors will walk past 109 East Palace Avenue in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and have no idea that they are passing the site that once served as Robert Oppenheimer’s office.

–

In the courtyard of a gift shop decorated with colorful ceramic frogs and dragonflies, it’s easy to overlook the historic marker.

Perhaps that’s fitting for a secret site.

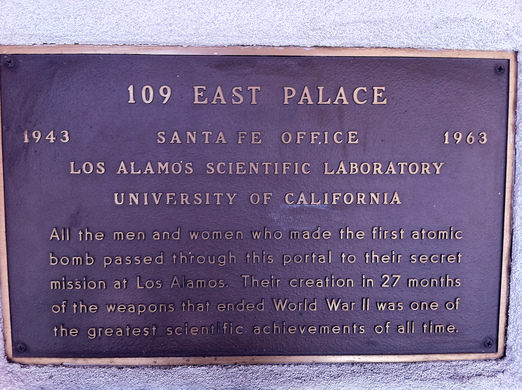

In the early 1940s, the world’s top scientists and their families trudged through this patio, bedraggled from a cross-country train trip. Most didn’t know where they were headed. All they had were classified orders to report to the address “109 East Palace, Santa Fe, New Mexico”. When they opened the wrought iron gate, they entered what the National Historical Landmark plaque calls a “portal to their secret mission”, which was to build the atomic bomb.

The Spanish colonial city of Santa Fe is known for its adobe buildings and art galleries (Credit: DenisTangneyJr/Getty Images)

–

“They came in through the courtyard,” said Marianne Kapoun, who with her husband owns The Rainbow Man gift shop, which occupies the formerly classified facility. Visitors now enter the shop through a front door; the historical entrance where scientists like Enrico Fermi and Richard Feynman once passed, is blocked, and the walkway cluttered with dangling ceramic chiles and hand-painted jack-o-lantern gourds.

The newcomers, which included a contingent of British scientists, were issued security passes and loaded from the facility onto a bus or a Jeep for the last leg of their journey. Their destination lay 35 miles away, up tortuous, unpaved mountain roads, in the hidden settlement of Los Alamos. And what they eventually accomplished, the plaque says, was “one of the greatest scientific achievements in human history”.

But few modern visitors to Santa Fe, a Spanish colonial city known for its adobe buildings and art galleries, realize they’re crossing paths with Nobel laureates – and a nest of spies.

During World War Two, the small city was on the frontlines of the race to build the atomic bomb. Over a period of 27 months, the US Army built the secret Los Alamos research laboratory in the Jémez Mountains and designed an unimaginably powerful weapon that eventually destroyed two Japanese cities, effectively ending the war and ushering in the atomic age.

Visitors to Los Alamos can see replicas of Little Boy and Fat Man, the atomic bombs developed at the lab (Credit: Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

–

The East Palace address, located half a block from the historic Santa Fe Plaza, was the only public-facing site of the Manhattan Project, the code name for the bomb-building effort. The storefront, marked with an inconspicuous sign reading “US ENG-RS”, an abbreviation for “Engineers”, handled correspondence for Los Alamos and processed new residents.

“These rooms right here were the offices,” Kapoun said, waving her hand past guidebooks and historical Native American photographs on sale in the store’s back room.

You may also be interested in:

• The invention that inspired a New York tradition

• The US’ surreal alien landscape

• A strange museum at the ‘center of the world’

The gift shop occupies a mere corner of a 17th-Century hacienda that once belonged to a Spanish conquistador and covers most of a city block. The building is also home to the popular Shed Restaurant, where lines form daily for its green chile enchiladas.

The US military history of 109 East Palace dates to 1939, when Albert Einstein wrote a letter to US president Franklin D Roosevelt warning that the Germans were on the cusp of developing an atomic weapon. Eventually Robert Oppenheimer, a physicist at the University of California, was tasked with leading the effort to beat them to it. He chose the remote Los Alamos Ranch boarding school to build a military research site.

The Rainbow Man gift shop at the Manhattan Project’s formerly classified facility (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

–

As the project geared up in 1943, Oppenheimer established a five-room Santa Fe office on East Palace and hired a personable young widow named Dorothy McKibbin to be his assistant. She became the public face of the project, welcoming scientists and other recruits and shooing away inquiries from curious locals. Historians now call her the “First Lady of Los Alamos”.

The US Army hoped Los Alamos’ isolation would keep its activities hidden. Officially, the lab didn’t exist. The entire project and its eventual thousands of residents shared the mailing address of PO Box 1663, Santa Fe, which was even listed on the birth certificates of babies born in Los Alamos during the war.

People come in to ask about it every day

Oppenheimer recruited top academics to join the effort but could provide little information due to security concerns. So scientists started to arrive at a windswept train station in nearby remote Lamy, New Mexico, knowing only to report to an address in downtown Santa Fe.

109 East Palace marker – Paige Henderson on Flickr [Creative Commons]

–

Some of the researchers missed the small office sign and wandered the plaza for hours looking for 109 East Palace. Even now, finding the historic site is somewhat complicated.

“People come in to ask about it every day,” said Beverly Andorfer, who works at Chocolate + Cashmere, which sells sweets and plush women’s wear. Although the shop is located at 109 East Palace, it’s not the right spot. A remodeling years ago shifted the building’s addresses, so visitors seeking atomic history must look for a painted placard next door pointing to the bronze marker.

Robert Oppenheimer, a physicist at the University of California, was tasked with developing the first atomic bomb (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

Robert Oppenheimer, a physicist at the University of California, was tasked with developing the first atomic bomb (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)Those wanting to see the actual entrance – the portal, if you will – must follow the scientists’ path up the hill to Los Alamos, which is still home to a US Energy Department laboratory. Today it’s an easy 45-minute drive, and although parts of what is now a city of 12,000 remain off-limits to visitors, it has several public heritage sites.

At Los Alamos History Museum, for example, the original wrought iron gate from 109 East Palace hangs at the end of a long gallery. Walking down a ramp toward the entryway, one can momentarily step in the shoes of a theoretical physicist wondering what awaits on the other side of the transom.

A few blocks away at the Bradbury Science Center, visitors pose for selfies with replicas of Little Boy and Fat Man, the bombs developed at the lab and ultimately dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And at the nearby Manhattan Project National Historical Park visitor center, children can don a suit jacket and “pork pie hat” to dress up as Oppenheimer, or slip on a cardigan and pretend to be McKibbin presiding over the Santa Fe office.

A self-guided walking tour takes visitors by Bathtub Row, a block of houses from the original boarding school that were the only buildings on the military installation equipped with bathtubs. During the war, residents endured “rustic conditions” as the army raced to build the facility, and the population soared to more than 6,000. Eventually, amenities like a school, medical clinic and stores were added.

Scientists arrived at a windswept train station in Lamy, New Mexico, knowing only to report to an address in Santa Fe (Credit: Larry Bleiberg)

–

Indeed, the boomtown became a pressure cooker as researchers raced to develop the weapon. Strict security amplified the stress. Residents weren’t allowed to share their location with friends or family members who weren’t living on site.

But despite the secrecy, activities at Los Alamos did not go unnoticed, and spies descended on northern New Mexico.

In fact, Santa Fe was the site of what historians consider the most important Soviet espionage operation of the 20th Century. Just two months before the bomb dropped on Japan, scientist Klaus Fuchs, a German émigré who had resettled in England before coming to Los Alamos, rendezvoused with a communist agent named Harry Gold.

Visitors can retrace the spies’ path, synchronizing watches at the same jewellery store clock a block west of 109 East Palace, as the men did, and then walking a few blocks to the tiny Paseo de Peralta bridge. At the since-replaced crossing, the agents exchanged a packet of papers describing the bomb’s implosion mechanism, which Fuchs had stolen from the laboratory. It would jump-start the Soviet Union’s nuclear ambitions and launch the Cold War.

The first atomic bomb was tested on 16 July 1945 at Trinity Site in New Mexico as part of the Manhattan Project (Credit: Lena Marie Bethell/Getty Images)

–

But they were hardly the only operatives in the city. La Fonda hotel, a grand tourist lodge located a block south from 109 East Palace, once crawled with spies hoping to glean information from Los Alamos scientists unwinding at the bar.

I’m sure there are spies around today

“The intrigue happened right here in the lobby. This was the center of espionage,” said Allen Steele, a private guide who leads spy-themed walking tours in the area. Los Alamos, he notes, remains a hub of classified government research. “I’m sure there are spies around today,” he said.

A hotel employee who stopped to say hello looked around and nodded in agreement. After all, in a city where a gift shop was once a way-station for the world’s most brilliant scientists, things are not always what they seem.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

(For the source of this, and many other equally interesting articles, please visit: http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20200128-an-atomic-marker-hidden-in-plain-sight/)