Anyone who grew up reading Scott O’Dell’s classic Island of the Blue Dolphins was probably captivated by the main character. She is a young woman who lives on an island in the Pacific Ocean totally alone. Her entire tribe has left the island, while she remains behind. Many people may not know or realize that O’Dell based his novel on a real event and a real life: that of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolás Island.

Born sometime in the early 19th century — no one knows for certain when — the woman who would eventually be known as Juana María of San Nicolás Island spent a significant portion of her life completely isolated from human contact. Though she was ultimately removed from her solitude in 1853, her future off the island was a brief one.

Historians have been able to piece together relatively few facts about Juana’s life. Taken as a whole, they reveal a tragic, heartbreaking story of a woman who, even when found, still remained lost in so many ways. Like the Trail of Tears that Native Americans were forced to take to her east, Juana María’s story is one that maps the contours of 19th-century Native American tragedy at the hands of European colonialism.

There Were Only Around 20 People Left In Her Tribe By 1835

San Nicolás Island is one of California’s Channel Islands. Juana María’s tribe, known as the Nicoleños, lived on the island for somewhere around 10,000 years. Their long history on the island could not protect them from tragedy, however. In 1811 or 1814 — when Juana María may have been a small child — disaster struck. A group of Native Alaskan and Russian otter hunters attacked the island and devastated the local population. The tribe’s population had stood at 300 people, and it was reduced to dozens in the wake of the attack. By 1835, the population was around 20 individuals.

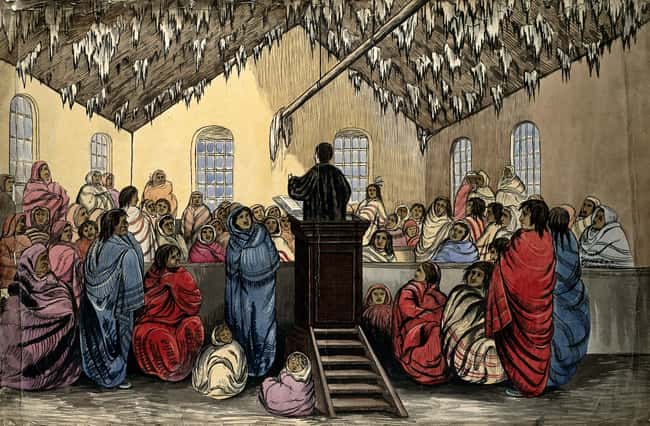

The Remaining Tribe Members Were Removed From The Island By Catholic Priests

In 1835, Juana María’s entire tribe was removed from San Nicolás Island. They didn’t leave by choice: Catholic priests on the mainland specifically requested that the entire Nicoleño tribe be evacuated. The priests’ motivations remain unclear. Were they evacuating the tribe because they worried they could not sustain their livelihood on San Nicolás Island? Or, more sinisterly, did they simply want more bodies to convert? Like much of Juana María’s story, these questions will probably never get answers.

Juana Got Left Behind On The Island, But No One Really Knows Why

The rest of Juana María’s small tribe was successfully removed from the island by Catholic priests in 1835. Juana didn’t make if off, however. Why was she left behind? There is no definitive answer. One story claims that she was absent from the group as they were being evacuated because she was out looking for her missing two-year-old child. Another story imagines Juana María jumping off the boat, believing that her little brother was still on the island. Whatever happened, an approaching storm meant that the ship departed San Nicolás in a hurry, leaving the woman behind.

Despite 18 Years In Solitude, She Was Discovered “Smiling”

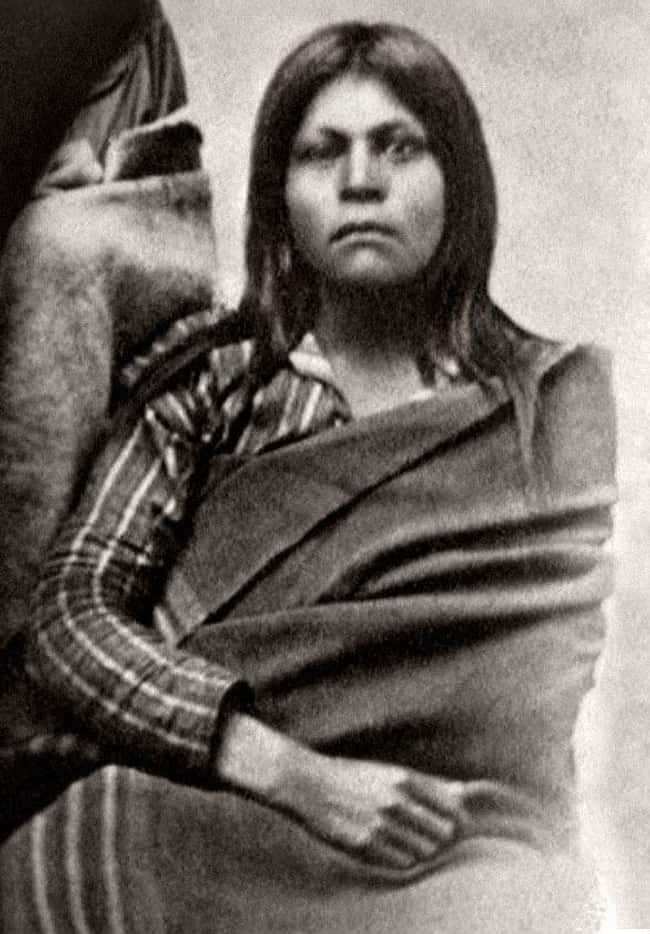

After several futile attempts at locating the lost woman who failed to depart with the rest of her tribe in 1835, a man by the name of George Nidever, finally located Juana María in 1853. In his memoir, The Life and Adventures of George Nidever, the Captain recounted the moment they discovered Juana, whom he described as an “old woman,” busily stripping whale blubber.

Instead of darting away from the Captain and his crew, she: “smiled and bowed, chattering away to them in an unintelligible language.” She was “of medium height… about 50 years old but… still strong and active. Her face was pleasing as she was continually smiling… Her clothing consisted of but a single garment of skins.”

She Lived Alone In A Whalebone Hut During Her 18 Solitary Years On The Island

The ship that left without Juana María never returned, and she was left alone on San Nicolás Island for 18 years. It’s hard to say what impact total isolation had on Juana María. But she was resourceful and went about her life; she hunted seals and ducks and made clothing and a shelter. When her rescuers found her in 1853, they discovered that she had built a hut out of whale bones and was probably living in a nearby cave.

When She Was Finally Found, She Had No Way Of Communicating With Anyone

Juana María’s solitude didn’t end as soon as she was re-discovered in 1853. When she was brought to the Santa Bárbara mission, she could not communicate with anyone. She was clearly speaking a Native language, one no one could understand. So, after she had been found, she couldn’t tell anyone her harrowing — or triumphant — story. To this day, scholars do not know what exact language Juana María spoke.

She Was The Last Surviving Member Of Her Tribe

Further tragedy awaited those Nicoleños who departed San Nicolás Island in 1835. The ship that took them from the island was the Peor es Nada [worse is nothing], which essentially translates to “better than nothing.” Though the ship ran aground in San Francisco Bay, the survivors moved to the San Gabriel Mission. Unfortunately, lack of immunity to the diseases they encountered on the mainland got the better of the Nicoleños, and they all died. By the time Juana María reached the mainland in 1853, she had become the last member of her tribe.

She Died After Only Seven Weeks On The Mainland

Though Juana María found human contact again in 1853, she only got to enjoy it for seven short weeks. After living in solitude for nearly two decades, her immune system was quite vulnerable when she arrived in Santa Bárbara. She quickly contracted dysentery. She tragically died on October 19, 1853, leaving essentially nothing but mystery in her wake.

No One Knows Her Real Name

There’s a good reason that Juana María is known simply as the “Lone Woman of San Nicolás Island” to many scholars: no one knows her real name. Catholic priests gave her the name Juana María only after she had been taken to Misión Santa Bárbara. In Island of the Blue Dolphins, she is named “Karana.” But there is no historical evidence for what her real name actually was.

She Became A Local Curiosity And Was Dubbed “The Wild Woman”

When she finally came to Santa Bárbara in 1853, the locals treated her like a curiosity, especially since no one could actually talk to her. She was dubbed the “wild woman.” Newspapers reported on how she was acclimating to life at the Santa Bárbara mission, even noting that she marveled at the horses around the mission and enjoyed coffee and liquor. She even performed songs and dances for those who came to look at the “wild woman.”

She Was Nursed By Captain Nidever’s Wife, Sinforosa

Upon her arrival in Santa Bárbara, Juana María went to stay at the home of the man who discovered her, Captain George Nidever. There, Captain Nidever’s wife, Sinforosa Sánchez Nidever, became Juana María’s companion and nurse. However, Juana Maríia’s time there lasted a tragically short seven weeks; not even her nurse and friend could save her from the dysentery she would contract on the mainland.

Priests Converted Her To Catholicism Probably Without Her Consent

Though Juana María was brought to the Santa Bárbara mission in 1853, there is absolutely no reason to believe that she was a Christian. After all, Misión Santa Bárbara was effectively a colonial outpost for Spanish Catholicism. But Juana’s religious affiliation changed over the course of her stay — with or without her consent. On October 19, 1853, a priest baptized her on her deathbed. Since she could not communicate, it is unlikely that she knew a priest was claiming her soul for the Christian God.

Many Of The Objects Associated With Her Have Been Lost

Juana María brought some objects with her to Santa Bárbara from San Nicolás Island, including bone needles that she had probably used to make a dress from cormorant feathers. Unfortunately, those objects had been housed in San Francisco and were destroyed in the great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. Additionally, her cormorant dress has also disappeared, notably, after being shipped to the Vatican. It’s as if all traces of her life have slipped away, further erasing her from the record.

Her Story Lives On In Fictional Accounts

Probably because so few facts could be gleaned from her life on San Nicolás, the woman known to history as Juana María has had a rich afterlife in fiction. As she captured the public’s imagination in her own time, she was characterized in specific ways. More recently, her story was fictionalized in Scott O’Dell’s hugely popular novel, Island of the Blue Dolphins. This celebrated novel – perhaps more than any other account of her life – has brought the mythology, legend, and story of the Lone Woman of San Nicolás Island to generations of young readers.

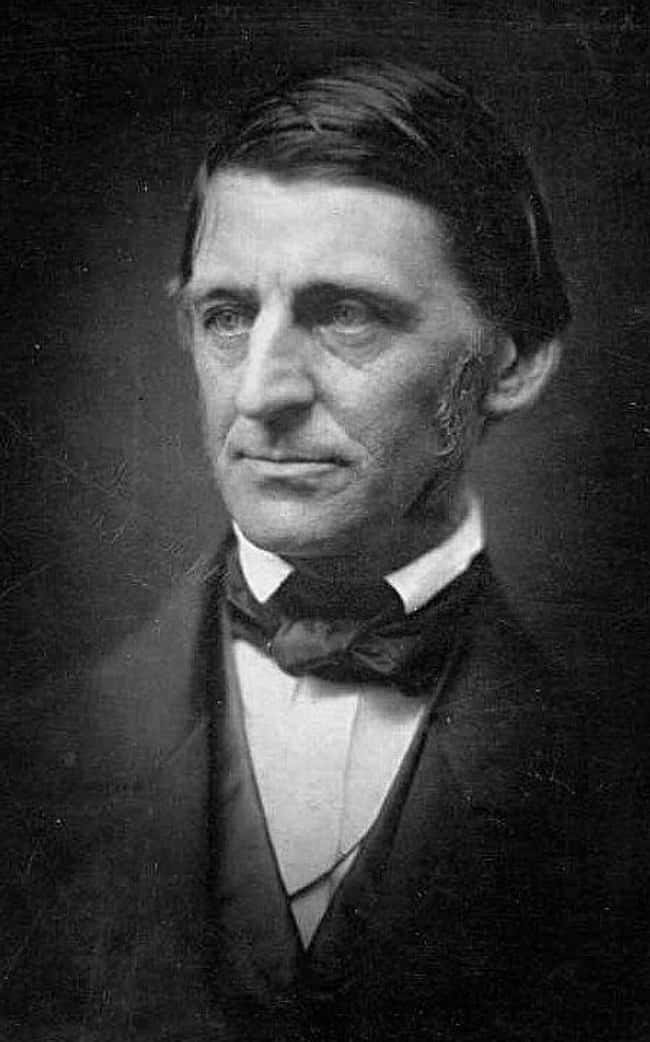

The Captain Who Discovered Her Inspired Ralph Waldo Emerson

Near the end of his life, Captain George Nidever, the man who finally found Juana María on San Nicolás Island after 18 years, decided to record the story of his life. And it is from this account, The Life and Adventures of George Nidever, that much of what modern audiences know about Juana María comes. Born in Tennessee in 1802, George Nidever’s life was one filled with incredible feats and stories, not least of which was his discovery of Juana María. And his autobiography – filled with these accounts – was wildly popular among American readers at the end of the 19th century. Among his fans was one Ralph Waldo Emerson, who included lyrics from a ballad about Nidever in his essay “Courage.”

–

(For the source of this, and many other equally intriguing articles, please visit: https://www.ranker.com/list/facts-about-juana-maria/setareh-janda/)