Brown, who used to fly F-18 carrier jets in the US Navy and is now flying 777s for a major airline, has spent the last 15 years working on a true flying car design – a proper high-speed jet plane crossed with a crazy luxury hypercar.

Brown’s dream is a vehicle that can draw more gawping attention at a car show or an air show than any single-mode vehicle. That can out-accelerate a Lamborghini on the road, then drive onto a runway, slide out a set of tucked-away wings, fire up a pair of roaring jet turbines and take to the air in a rush of speed unlike anything in the private jet market.

One that can cruise at more than 500 mph, perform cornering maneuvers at loadings up to 5G, do full barrel rolls and fly up to 850 miles without touching mandated fuel reserves. That can land without flaring, on extended shocks like the ones used in Baja and Trophy Trucks. That can do it with a genuine luxury approach to the interior instead of the utilitarian, metallic cockpits of the typical jet, and that can sell for hypercar money.

And things have come a ways since the GF7 design he showed us in 2014. For starters, the new Firenze Lanciare design looks a lot more like a hypercar than some weirdly folded aeroplane when it’s in street mode. This is chiefly thanks to a new hideaway wing design Brown has been working on, as well as a chassis and suspension setup borrowed from extreme off-road racing events and the widespread availability of high-powered electric drivetrains.

The Firenze Lanciare design

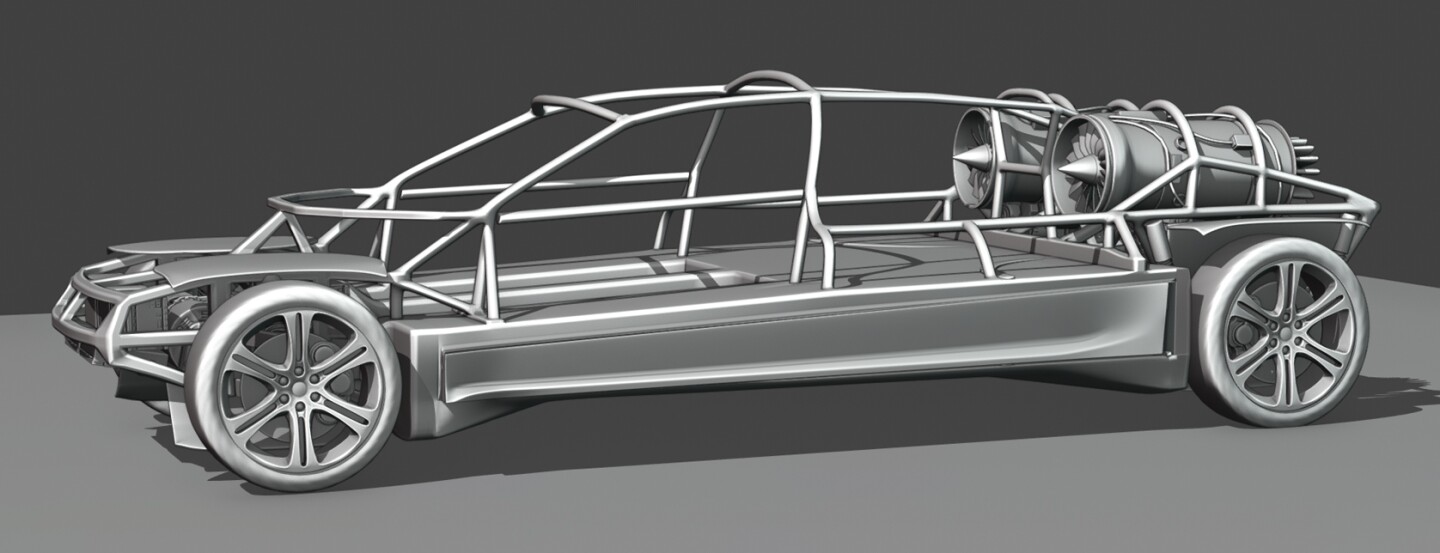

The Lanciare starts out as an extra-long, lightweight chromoly tube frame designed in conjunction with Armada Engineering. Armada is a well-known and respected builder of Trophy Trucks, Baja buggies and other high-speed, high-impact offroad racers. Brown wanted something that could take some serious stresses, both in the air and upon landing.

“I’m looking for a structure that you won’t have to flare to land,” Brown tells us over the phone from California. “It takes a lot of skill to land an aircraft softly, but there’s been a hundred airplanes made to land on aircraft carriers that you didn’t have to land softly, you can just pound ’em on. Being an ex-carrier jet pilot myself, I know how easy it is when you don’t have to flare to land. Just point at the runway and hit it. And that completely reduces your requirement to be a great pilot.”

The suspension to handle these kinds of hard landings, he says, already exists in the off-road racing world: dual-chamber racing truck suspension can offer up to 10 inches (25 cm) of travel, in which the first two thirds of that travel can be set solely to absorb landing forces without springing back up. The final third can give you a nice ride on the road, and with an active ride height adjustment system you could easily raise the vehicle right up for rough roads.

At the bottom of that chromoly frame there’s a flattish aluminum structural case that acts as a floor for the rest of the design. Within that “wing box” lie the two wings, folding away between the wheels and under the cabin in road mode. When flight mode is engaged, they’re drawn out to their full 27-foot wingspan using an electric chain motor system, then raised up to equal heights on a set of jack screws, ready for takeoff.

–

The road drivetrain, says Brown, could be pulled straight from a high-performance Tesla or built to order. There’s plenty of room for batteries, with an initial spec of 100 kWh scoped out purely to drive the wheels in road mode.

The cabin offers a sportscar-style seating layout: two front seats for comfort and two rear seats best suited to kids or short trips. Here, among other ways, the design diverges from our friend Dezso Molnar’s firmly-stated ideals (to recap, Molnar says when you add seats “you push the design into a place it doesn’t need to go to allocate space and strength and range for people that are not necessarily in attendance. You’re building machines for people that don’t exist.”)

Brown chuckles when I ask if that back row could be deleted to shorten the car’s leviathan 6.43-meter (253-inch) length, which increases to 7.52 meters (296 inches) when the large rear stabilizer wing is lifted. “Yeah, you could do things like that,” he laughs. “I blame my wife for insisting it’s a four-seater, but this is a common-law state, so she’s part owner!”

The cabin is pressurized, and also sound-insulated using foam core with a hardened carbon fiber wrap, and leather and Alcantara trims backed with further noise isolation. Brown is insistent that the cabin should be fitted out to equal a Maserati supercar cabin in luxury rather than to emulate the utilitarian, stark, metallic cabins favored by the traditional aviation industry. “The people that have the money for these things,” he says, “they know what a great interior looks like, but there aren’t any planes that offer that right now.”

Behind the cabin lives a large, 300-gallon fuel tank, and this, together with a pair of huge air intakes behind the side windows, feeds a pair of compact jet turbine engines (Williams FJ-33 or similar) producing somewhere around 4,000 pounds of thrust between them. This new class of small turbofans was designed for a Very Light Jet market that never took off, so to speak, and both Williams and Pratt & Whitney have expressed an informal interest in loaning Brown engines when it comes time to prototype the Lanciare.

In terms of controls, this beast will offer full and separate control schemes for the car and aircraft modes. Thus, you’ll get a regular steering wheel, dash, brake and gas pedals to drive the electric car with, and when it’s time to fly, you can shift your feet down and off to the side onto the rudder pedals, grab onto a central jet fighter-style stick in the center console where the gearshift might be in a combustion car, and a throttle mounted in the door. Since the stick is central, your passenger can take over as co-pilot or instructor thanks to a throttle in the opposite door as well. Digital displays in the left side, right side and center of the dash would give you all the information readouts necessary for flight and navigation.

Brown cheerfully points out that the Lanciare’s status as an aircraft makes this thing a hypercar whose acceleration and top speed you can actually use: “You’d get zero to takeoff speed as fast as any hypercar, and you could do it all day long without worrying about getting tickets. That’d be fun, you don’t need special permission or anything, it’s just part of taking off, you get a runway all to yourself.

“So you use all this electric torque, plus jet engines, and you’ve got yourself a next-generation thrill. You can take off in a crazy-short distance, proper neck-snapping acceleration, and then you’ve got jet engines and wings, so instead of having a 300 mph top speed that you just barely tag and then you have to stop again, even in the best places in this world, you can accelerate all the way up to 500 mph every time you get airborne, climb up to 10,000 feet and boom. Get to your destination super fast.”

What’s it cost?

Brown says at a conservative estimate he could get the aircraft prototyped for US$20-40 million, working with Armada on the frame and EV West on the powertrain. He’s also in discussions with a well-known and respected aircraft builder (which we can’t name) that has provisionally indicated it’d be on board for a run of 10 or more units.

Each car, he figures, would cost around 5-7 million. “That’s not a bad number for the hypercar market,” he says, “you can see how the cost of everything is just skyrocketing lately. I mean, Lamborghini’s selling a three million dollar car. To get you to 500 mph, five to seven million is a small price to pay! It sounds like a lot, but a really cheap corporate jet is like 2-2.5 million dollars. That’s the bare bones, the smallest, they don’t fly very fast or far, this would outperform them on every level.”

Certification, on the other hand, would be a crippling expense. Brown estimates it could cost up to US$2 billion to get the Firenze Lanciare fully FAA certified for series production, let alone what it would cost to have it fully tested and approved for road use as a production car.

“Once you’ve got a prototype built,” says Brown, “you can get an uncertified version, and if a company wanted, they could use it for their own transportation, but you couldn’t use it for hire. It would still have all the safety you’d expect on an airplane; twin turbine reliability and redundancy, crazy capacity to climb, all that kind of stuff.”

Brown would prefer to leave full certification for later down the track, when larger companies can get involved. “I don’t want to get into the business of production. I want to test the market for interest, find the people that want them, get the names, and after we’ve learned the lessons of the first ten built, we’d want to sell it to Embraer, Learjet, Cessna, the corporate jet makers that have all the engineering, the facilities to make it into a viable, safe product and get it done. It’s a difficult task for a startup company to go from nothing to full production on something like this.”

Who’s gonna buy one?

Brown sees potential markets in the resource sector, where city-based executives could use it to save bulk time heading out to regional and remote sites. No car or welcome party would need to be waiting at the airstrip, and if traffic was banked up on the way to one city airstrip, you could turn and head straight for another, phoning in the changes to your flight plan and getting gate codes through phone apps to minimize any waiting on the ground.

But it’s more likely, he thinks, that the early units will sell to well-heeled aviators and hypercar buyers keen to add to their collections. “There’s a lot of owner-operators that have their own personal jets. They’re pilots, they’re wealthy enough, they can afford it, so they just buy it and fly it themselves. And they totally dig this kind of thing. They collect cars, they collect jets, they fly their own jets, and those kind of guys are probably going to buy the first ten.

“None of the small business jets are performance airplanes. If you want something that can handle five Gs, do complete rolls, you have to go and buy an ex-military jet. An L-39 trainer or something, you see lots of those at air shows. Those are performance airplanes, but they’re not nice inside at all. Lots of metal, big knobs hanging everywhere … There’s a place for that, and those guys wouldn’t sell their L-39 if they got this, but there’s also a place that’s completely unexplored, where you have a complete, luxurious, nicely refined materials, quiet cockpit that you can put your wife in and she doesn’t feel like she was in a box car.”

Brown is frustrated to see billions of dollars pouring into the eVTOL sector to develop aircraft he feels will be far less useful, that’ll require last-several-mile transport at either end of the journey and will do little that a helicopter can’t.

“Uber Elevate said five years ago that by 2020, we were gonna have VTOL Ubers that would take us everywhere,” he says. “People in the industry were like yeah, fat chance, that’s not gonna happen. And it’s totally not happening. So they keep moving the horizon. Now it’s 2023, soon it’s gonna be 2025, by 2030, we’ll probably have a viable passenger version. And that’ll be great, it’ll be awesome.

“But they feed everyone a line to get the investment money. I have a hard time doing that, so I’m being as up-front as possible, trying to overestimate time, cost and weight rather than underestimating, but the industry doesn’t seem to function on realistic expectations.”

It doesn’t seem that far-fetched to us that Brown will find his ten buyers. Our own Mike Hanlon put together this exhaustive list of the 100 most expensive cars ever sold at auction, and there’s several people who’ve paid sums of money for a single used car that could conceivably fund a full prototype of the Firenze Lanciare. Bugatti stuck out its hand and asked more than 12 million bucks for its La Voiture Noire, with a straight face and everything. None of those things have a pair of big fat jet turbines in the back, or the ability to point down a runway, lift off and do 500 mph for a full hour and a half.

Five-to-seven million dollar cars are becoming common as muck these days as wealth continues to funnel upwards at extraordinary rates. We see no reason why something as outlandish and extraordinary as this shouldn’t be tempting to buyers at this end of the market; if the aesthetics are done right it’d be the unquestioned jewel of any car show or air show on Earth.

It would also offer a degree of utility that people have dreamed about as long as cars have rolled around the Earth. Somebody just needs to get the ball rolling, and Greg Brown has put a solid 15 years into it for his part. And even if this is clearly going to be a boy’s toy for the ultra-rich, we sure hope to see it get built.

Source: Firenze Lanciare

–