–

By Jerone Andrews

2021 Mar 24

–

–

On 2020 Oct 03, the White House published two photographs of Donald Trump, signing papers and reading briefings. The day before, Trump had announced he had caught the coronavirus and these photos were apparently released to show that he was in rude health (strong and healthy). His daughter Ivanka tweeted one of the photos with the caption: “Nothing can stop him working for the American people. RELENTLESS!”

But keen-eyed observers noticed something unusual.

Two photos of Trump from inside the hospital where he was treated for coronavirus (Credit: EPA/Joyce N Boghosia/The White House)

Two photos of Trump from inside the hospital where he was treated for coronavirus (Credit: EPA/Joyce N Boghosia/The White House)

The photos were taken in two different rooms in Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. In one Trump wears a jacket, in the other just a shirt. Coupled with public statements about his positive health and work ethic, the implication was that he had been handling his presidential duties all day, despite his illness. The photo timestamps, however, said otherwise. The images were taken 10 minutes apart.

Of course, there are other possible explanations for why they were shot so closely together. Perhaps the photographer only had access for 10 minutes, and maybe Trump always intended to switch rooms during that window. However, the White House can’t have been happy that people noticed the timestamps. It led news outlets and commentators to talk about whether the images were staged for a photoshoot to project a political message, and to question whether Trump really was working so “relentlessly” after all.

Hidden information inside digital photos can reveal much more than photographers and their subjects bargain for

It’s not the only time hidden information inside a digital photo has led to unintended consequences. Just ask John McAfee, founder of the eponymous antivirus software. In 2012, he was on the run from the Belizean authorities in Central America. Reporters from Vice magazine tracked him down and published an image of him online, under the headline “We Are With John McAfee Right Now, Suckers”. Yet without them realizing, location data embedded in the photo inadvertently revealed that McAfee was in Guatemala. He was soon found, and detained.

These are just two examples of how hidden information inside digital photos can reveal much more than the photographers and their subjects bargained for. Could your own photos be sharing more details with the world than you realize, too?

John McAfee speaks to journalists at the Supreme Court in Guatemala, after his location was revealed by a photo (Credit: Johan Ordóñez/Getty Images)

John McAfee speaks to journalists at the Supreme Court in Guatemala, after his location was revealed by a photo (Credit: Johan Ordóñez/Getty Images)–

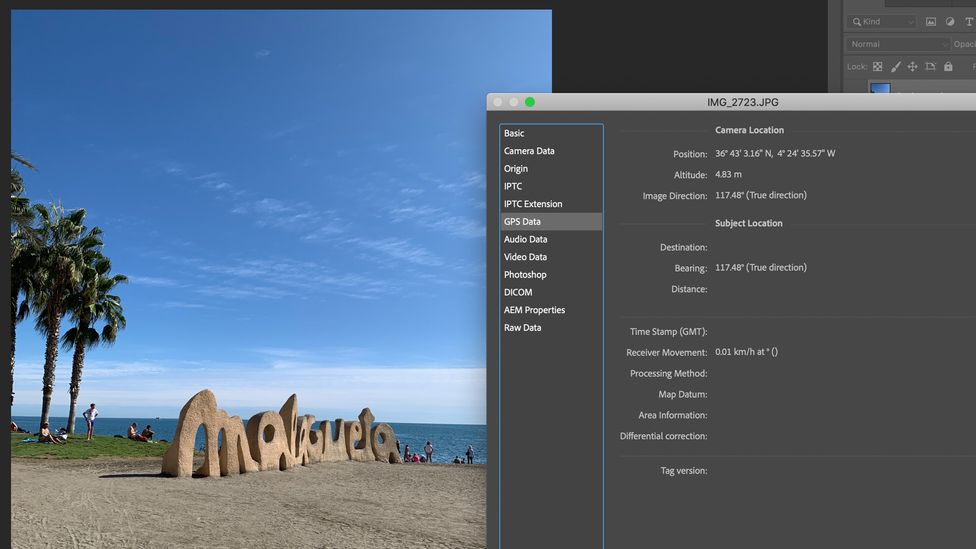

When you take a photo, your smartphone or digital camera stores “metadata” within the image file. This automatically and parasitically burrows itself into every photo you take. It is data about data, providing identifying information such as when and where an image was captured, and what type of camera was used.

It is not impossible to expunge metadata, using freely available tools such as ExifTool. But many people don’t even realize the data is there, let alone how it might be used, so they don’t bother to do anything about it before they post images online. Some social media platforms remove information like geolocation (though only from public view), but many other websites do not.

This lack of awareness has proven useful for police investigators, to help them place unwitting criminals at a scene. But it also poses a privacy problem for law-abiding citizens if the authorities can track their activities through images on their camera and social media. And unfortunately, savvy criminals can use the same tricks as the police: if they can discover where and when a photo was taken, it can leave you vulnerable to crimes such as burglary or stalking.

A view of photo location metadata inside Adobe Photoshop (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld)

A view of photo location metadata inside Adobe Photoshop (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld)

But metadata is not the only thing hidden in your photos. There is also a unique personal identifier linking every image you capture to the specific camera used, but it’s one you’d probably never suspect. Even professional photographers might not realize or remember that it’s there.

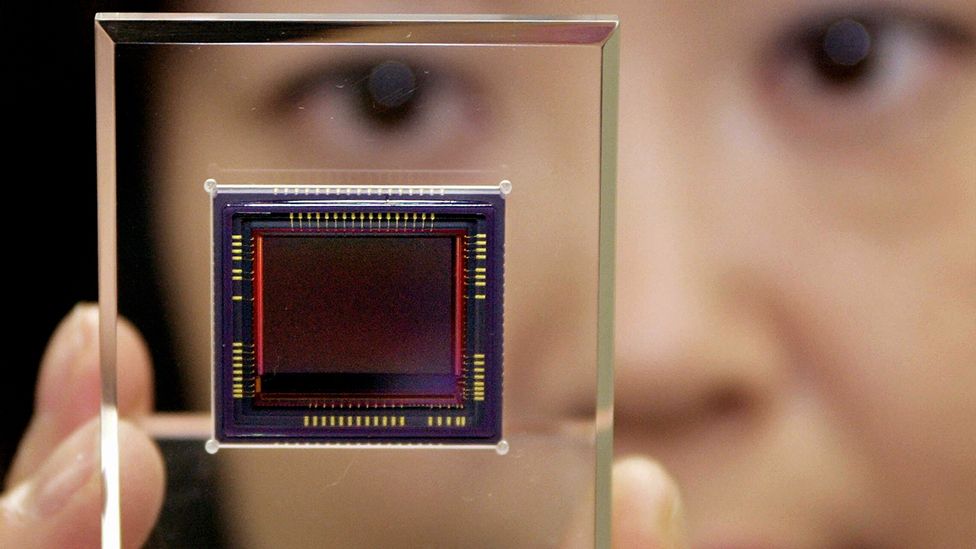

To understand what this identifier is, you first have to understand how a photo is captured. Central to every digital camera, including those inside smartphones, is its imaging sensor. This is composed of a grid of millions of silicon “photosites”, which are cavities that absorb photons (light). Due to a phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect, the absorption of photons causes a photosite to eject electrons a bit like a nightclub bouncer.

The electrical charge of the electrons emitted from a photosite is measured and converted into a digital value. This results in a single value for each photosite, which describes the amount of light detected. And this is how a photo is formed. Or etymologically speaking, a drawing with light.

However, due to imperfections in the manufacturing process of imaging sensors, the dimensions of each photosite differs ever so slightly. And when coupled with the inherent inhomogeneity of their silicon material, the ability of each photosite to convert photons to electrons varies. This results in some photosites being more or less sensitive to light than they should be, independent of what is being photographed.

So, even if you used two cameras of the same make and model to snap a uniformly lit surface – where every point on the surface has the same brightness – there’d be subtle differences unique to each camera.

Much like snowflakes, no two imaging sensors are alike.

The different sensitivities of the photosites creates a type of imperceptible image watermark. Although unintentional, it acts like a fingerprint, unique to your camera’s sensor, which is imprinted onto every photo you take. Much like snowflakes, no two imaging sensors are alike.

In the digital image forensics community, this sensor fingerprint is known as “photo response non-uniformity”. And it’s “difficult to remove even when one tries”, says Jessica Fridrich of Binghamton University in New York state. It’s inherent to the sensor, as opposed to measures, such as photo metadata, that are “intentionally implemented”, she explains.

Fake photos

The upside of the non-uniformity fingerprint technique is that it can help researchers like Fridrich identify faked images.

In principle, photos constitute a rich reference to the physical world, and can therefore be used for their evidential value, since they portray what is. However, in the current climate of disinformation – exacerbated by the ready supply of image editing software – it has become increasingly important to know the origin, integrity and nature of digital images.

Fridrich has patented the photo fingerprinting technique, and it has been officially approved for use as forensic evidence in court cases in the United States. It means investigators can identify manipulated areas, associate it with a specific camera device, or establish its processing history.

Fridrich believes this technology could also be used to reveal AI-generated synthetic imagery known as deepfakes. And tentative research corroborates this. The distinguishing feature of a deepfake is its photorealism. Having gained infamy in 2018, due to their use in pornographic videos, deepfakes present a tangible threat to the information ecosystem. If we are unable to differentiate between what is real and what is not, then all media consumed can be reasonably doubted.

You may also like:

- The hidden signs that can reveal a fake photo

- The greatest security threat of the post-truth age

- The intriguing history of ghost photography

In the post-truth age, the ability to spot fakery is obviously a positive development. But at the same time such photo-fingerprinting methods can “have positive and negative uses”, says Hany Farid, a professor in electrical engineering and computer sciences at the University of California, Berkeley and founder of digital image forensics.

While Farid has used the non-uniformity technique to link photos back to specific cameras in child sexual abuse cases – a clear benefit – he also cautions that as “with any identification technology, care should be taken to make sure that it is not misused”. This is particularly pertinent to individuals such as human rights’ activists, photojournalists and whistle-blowers, whose safety may depend upon their anonymity. According to Farid, such individuals could be “targeted by linking an image back to their device or previously posted [online] images”.

When considering these privacy issues, we might draw parallels with another technology. Many color printers add secret tracking dots to documents: virtually invisible yellow dots that reveal a printer’s serial number, as well as the date and time a document was printed. In 2017, these dots may have been used by the FBI in the identification of Reality Winner as the source of a leaked National Security Agency document, which detailed alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

Regardless of your opinion on whistleblowing, these surveillance techniques could affect us all. The European Commission has voiced concerns, suggesting that such mechanisms could erode an individual’s “right to privacy and private life“. If we view photo fingerprints as being equivalent to a printer’s serial number, then this prompts us to ask whether photo response non-uniformity also violates an individual’s right to protection of their personal data.

Despite our chronic predisposition to self-disclose over the internet, we vehemently reserve the right to privacy. In principle, people should be able to decide the degree to which information about themselves is communicated externally. But in light of what we now know about forensic photo tracking, such self-determination may only be an illusion of control.

Standard metadata is difficult enough to avoid – you have to scrub it afterwards, and the only piece of information you can stop from being created in the first instance is photo geolocation. Photo response non-uniformity, however, is far more difficult to extricate. Technically, it should be possible to suppress, for example, by reducing the image resolution, says Farid. But, by how much? This of course depends on many factors such as the type of device used for image capture, as well as the fingerprint matching algorithm employed. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to fingerprint removal.

So, how concerned should we be about photo response non-uniformity from an ethical standpoint? When I asked Fridrich about the implications of its various applications, she candidly remarked, “a carpenter can do wonders with a hammer, but a hammer can also kill”. While no one is saying that the hidden data inside your photos could be deadly, her point is that this is a technique that could cause harm in the wrong hands.

You don’t need to be Donald Trump or John McAfee to be affected by the rise of photo metadata and fingerprints. So the next time you take a snap with your smartphone, you might pause to reflect on how much more is being captured than what you see through the lens.

—

Jerone Andrews wrote this article while working as a researcher at University College London, as part of a media fellowship organized by the British Science Association.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

–