Ghost forest panorama in coastal North Carolina. Emily Ury, CC BY-ND

Ghost forest panorama in coastal North Carolina. Emily Ury, CC BY-ND

–

Trekking out to my research sites near North Carolina’s Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, I slog through knee-deep water on a section of trail that is completely submerged. Permanent flooding has become commonplace on this low-lying peninsula, nestled behind North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The trees growing in the water are small and stunted. Many are dead.

Throughout coastal North Carolina, evidence of forest die-off is everywhere. Nearly every roadside ditch I pass while driving around the region is lined with dead or dying trees.

As an ecologist studying wetland response to sea level rise, I know this flooding is evidence that climate change is altering landscapes along the Atlantic coast. It’s emblematic of environmental changes that also threaten wildlife, ecosystems, and local farms and forestry businesses.

Like all living organisms, trees die. But what is happening here is not normal. Large patches of trees are dying simultaneously, and saplings aren’t growing to take their place. And it’s not just a local issue: Seawater is raising salt levels in coastal woodlands along the entire Atlantic Coastal Plain, from Maine to Florida. Huge swaths of contiguous forest are dying. They’re now known in the scientific community as “ghost forests.”

–

The insidious role of salt

Sea level rise driven by climate change is making wetlands wetter in many parts of the world. It’s also making them saltier.

In 2016 I began working in a forested North Carolina wetland to study the effect of salt on its plants and soils. Every couple of months, I suit up in heavy rubber waders and a mesh shirt for protection from biting insects, and haul over 100 pounds of salt and other equipment out along the flooded trail to my research site. We are salting an area about the size of a tennis court, seeking to mimic the effects of sea level rise.

After two years of effort, the salt didn’t seem to be affecting the plants or soil processes that we were monitoring. I realized that instead of waiting around for our experimental salt to slowly kill these trees, the question I needed to answer was how many trees had already died, and how much more wetland area was vulnerable. To find answers, I had to go to sites where the trees were already dead.

Rising seas are inundating North Carolina’s coast, and saltwater is seeping into wetland soils. Salts move through groundwater during phases when freshwater is depleted, such as during droughts. Saltwater also moves through canals and ditches, penetrating inland with help from wind and high tides. Dead trees with pale trunks, devoid of leaves and limbs, are a telltale sign of high salt levels in the soil. A 2019 report called them “wooden tombstones.”

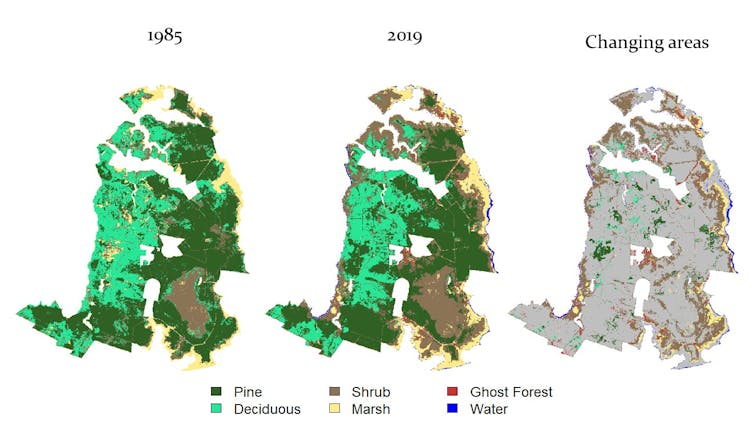

As the trees die, more salt-tolerant shrubs and grasses move in to take their place. In a newly published study that I coauthored with Emily Bernhardt and Justin Wright at Duke University and Xi Yang at the University of Virginia, we show that in North Carolina this shift has been dramatic.

The state’s coastal region has suffered a rapid and widespread loss of forest, with cascading impacts on wildlife, including the endangered red wolf and red-cockaded woodpecker. Wetland forests sequester and store large quantities of carbon, so forest die-offs also contribute to further climate change.

–

Assessing ghost forests from space

To understand where and how quickly these forests are changing, I needed a bird’s-eye perspective. This perspective comes from satellites like NASA’s Earth Observing System, which are important sources of scientific and environmental data.

–

Since 1972, Landsat satellites, jointly operated by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey, have captured continuous images of Earth’s land surface that reveal both natural and human-induced change. We used Landsat images to quantify changes in coastal vegetation since 1984 and referenced high-resolution Google Earth images to spot ghost forests. Computer analysis helped identify similar patches of dead trees across the entire landscape.

–

The results were shocking. We found that more than 10% of forested wetland within the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge was lost over the past 35 years. This is federally protected land, with no other human activity that could be killing off the forest.

Rapid sea level rise seems to be outpacing the ability of these forests to adapt to wetter, saltier conditions. Extreme weather events, fueled by climate change, are causing further damage from heavy storms, more frequent hurricanes and drought.

We found that the largest annual loss of forest cover within our study area occurred in 2012, following a period of extreme drought, forest fires and storm surges from Hurricane Irene in August 2011. This triple whammy seemed to have been a tipping point that caused mass tree die-offs across the region.

–

Should scientists fight the transition or assist it?

As global sea levels continue to rise, coastal woodlands from the Gulf of México to the Chesapeake Bay and elsewhere around the world could also suffer major losses from saltwater intrusion. Many people in the conservation community are rethinking land management approaches and exploring more adaptive strategies, such as facilitating forests’ inevitable transition into salt marshes or other coastal landscapes.

For example, in North Carolina the Nature Conservancy is carrying out some adaptive management approaches, such as creating “living shorelines” made from plants, sand and rock to provide natural buffering from storm surges.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

A more radical approach would be to introduce marsh plants that are salt-tolerant in threatened zones. This strategy is controversial because it goes against the desire to try to preserve ecosystems exactly as they are.

But if forests are dying anyway, having a salt marsh is a far better outcome than allowing a wetland to be reduced to open water. While open water isn’t inherently bad, it does not provide the many ecological benefits that a salt marsh affords. Proactive management may prolong the lifespan of coastal wetlands, enabling them to continue storing carbon, providing habitat, enhancing water quality and protecting productive farm and forest land in coastal regions.

–

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 124,600 academics and researchers from 3,968 institutions.