A new book tells the story of the painstaking process to preserve the 1,200-year-old Faddan More Psalter.

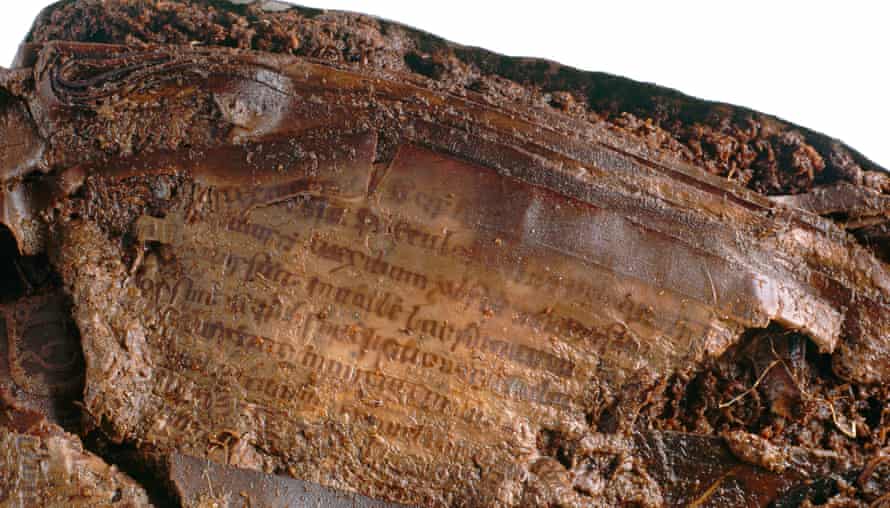

Letters and fragments from the Faddan More Psalter. Photograph: National Museum of Ireland

Letters and fragments from the Faddan More Psalter. Photograph: National Museum of Ireland

–

Last modified on 2021 Nov 21

–

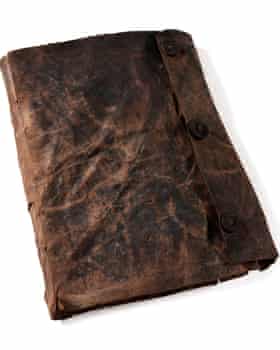

One summer’s day in Tipperary as peat was being dug from a bog, a button peered out from the freshly cut earth. The find set off a five-year journey of conservation to retrieve and preserve what lay beyond: a 1,200-year-old psalm book in its original cover.

Bogs across Europe have thrown up all sorts of relics of the ancient past, from naturally preserved bodies to vessels containing butter more than a millennium old, but the 2006 discovery of an entire early medieval manuscript, entombed in a wet time capsule for so long, was unprecedented, said the National Museum of Ireland.

–

The book fell open upon discovery to reveal the Latin words in ualle lacrimarum (in the valley of tears), which identified it as a book of psalms. One particularly unexpected feature was the vegetable-tanned leather cover with a papyrus reed lining, suggesting the monks could have had trade links with Egypt.

“It still blows me away,” said John Gillis, the chief manuscript conservationist at Trinity College Dublin, home of the Book of Kells, the Book of Armagh and 450 other medieval Latin manuscripts. “It was by far and away the most challenging, most interesting project I have ever undertaken – and to put that in context, I am surrounded by these iconic manuscripts.”

–

Ten years after going on display at the National Museum in Dublin, the Faddan More Psalter is one of Ireland’s top 10 treasures and now the subject of a 340-page book from the institution documenting every stage of the “terrifying” preservation process for future scholars.

“The fact that such a fragile organic object survived for a millennium in wet conditions, the fact that it was noticed … and the fact that a full bifolio survived and allowed Gillis to ascertain the codicological details of the psalter are all very much against the odds,” said Maeve Sikora, a keeper of Irish antiquities at the National Museum who supported Gillis with the work.

–

The process of stabilizing the book outside the bog, drying it and then unpicking and unfolding pages where possible was painstaking. Archaeologists placed the “conglomeration” of squashed pages, leather and turf in a walk-in cold store in the museum at 4C. But there was no manual in the world to guide Gillis on how to go about the task.

“I spent the first three months retrieving the mass from the fridge, bringing it up to my lab and just staring at it, trying to make sense of it before I could start any sort of intervention work. Because once you disturb it, you are in effect losing evidence,” Gillis said.

“Although the bog was responsible for its really poor condition, it was also responsible for locking it in its original condition.”

–

Initial examination was limited in order to mitigate further trauma. CT scans and X-rays to find 3D structures were excluded owing to concerns that they could accelerate the degradation.

After trying sophisticated versions of freeze-drying, vacuum-sealing, and drying with blotting paper, Gillis settled on a dewatering method using a vacuum chamber installed in the museum lab for four years to minimize shrinkage and decay.

It would take two years before all the folio fragments were in a dry and stable state before the daunting task of dismantling could begin, a process chronicled in the book out later this month, The Faddan More Psalter, The Discovery and Conservation of a Medieval Treasure.

–

“It was absolutely terrifying,” Gillis said of the responsibility he felt. “I heard from someone in the British Museum that there was a picture of the mass on the walls in a staff area there with the words ‘if you think you have a bad day ahead …’ You had this nerve-racking scenario of disturbing this material, which meant losing evidence, when the whole point was trying to gain as much information as possible.”

Many of the spaces between the iron gall letters had dissolved into the bog, leaving an alphabet soup of several thousand standalone letters. It would take months after the drying process to piece them all together, in sequence on the right pages.

–

“The rewards when you slowly lifted up a fragment, and suddenly beneath this little bit of decoration would appear, particularly the yellow pigment they used. It would kind of shine back at you,” Gillis said. “And you’d go: ‘Wow, I am the first person to see this in 1,200 years.’ So that kind of privilege made all the sleepless nights and racking of the brain worthwhile.

“It was the purest conservation I’ve ever carried out. There is no repair, I’ve attached nothing new. All I’ve done is captured and stabilized.”

–

–

Topics