The headstone of Father Damien, a Catholic saint who was canonized in 2009. Richard A. Cooke III/Corbis Historical via Getty Images

The headstone of Father Damien, a Catholic saint who was canonized in 2009. Richard A. Cooke III/Corbis Historical via Getty Images –

![]() By Teaching Fellow, University of Chicago Divinity School

By Teaching Fellow, University of Chicago Divinity School

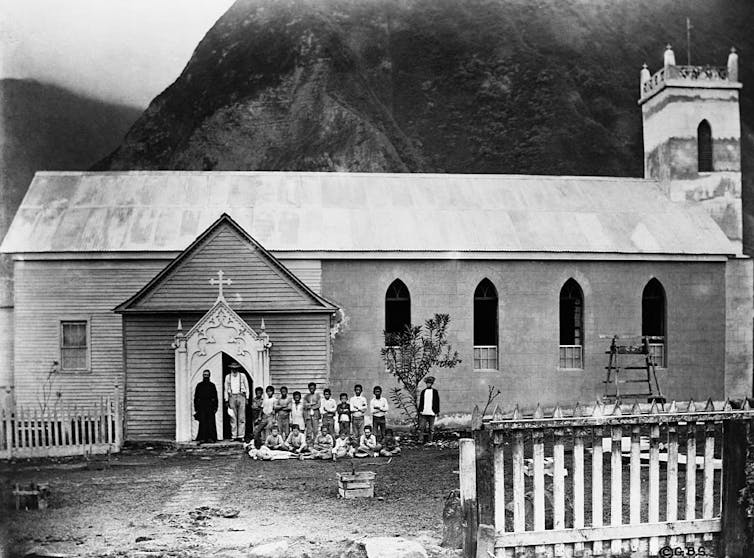

More than 8,000 people with leprosy fell victim to this policy of permanent segregation over the next century. Native Hawaiians renamed leprosy “ma’i ho’oka’awale ‘ohana”: the sickness that separates family. Surrounded by steep cliffs and treacherous ocean, the peninsula served as a natural prison and soon gathered a reputation as a de facto death sentence.

But in the Catholic Church, May 10 commemorates the day one man moved to Molokai willingly: Father Damien. Born Jozef De Veuster in Belgium, he came to Hawaii as a young Catholic missionary and spent the last 16 years of his life voluntarily living in the leprosy colony, before contracting the disease himself and dying in 1889.

Canonized as a saint in 2009, Father Damien was designated the patron saint of people with leprosy, or Hansen’s disease.

My research focuses on how Christian theology views socially stigmatized diseases, such as leprosy. Since the HIV/AIDS epidemic began in the 1980s, Damien has also become linked with the virus and inspired many Catholic groups that care for patients. His legacy illustrates the church’s complicated, often harmful views on HIV/AIDS – but has also helped people see those who suffer from stigmatized diseases with more agency and dignity.

Joining the community

Damien landed at Molokai on 1873 May 10. In a now famous letter to his brother, he wrote that he would make himself “a leper with lepers,” to “gain all to Christ.”

For over 2,000 years, “care” for people with leprosy has often been reduced to segregation. This was the case in Hawaii, where the Board of Health offered bounties to those who turned in suspected patients. The widespread belief that leprosy was an advanced stage of syphilis added an air of moral condemnation to the policy.

According to accounts such as “Kaluapapa: A Collective Memory,” which documents residents’ experiences in the colony, Damien employed his carpentry skills to build two chapels, new shelters for the residents, and a multitude of coffins. He provided rudimentary medical care, secured a fresh water supply, and established an orphanage. At a time when fear of being near people with leprosy was the norm, the priest also ate with residents from the same pot, and shared his pipe with them.

By the beginning of 1885, Damien began to show signs of having contracted leprosy, and in 1886 the priest formally became known as Admission #2886 to the settlements. Three years later, he succumbed to the disease.

–

Patron saint

Damien’s ministry garnered an international audience, elevating him to something of a celebrity, and his death prompted an immediate response. The future king of England, Edward VII, proposed to erect a monument to Damien on Molokai, to establish a ward devoted to leprosy in a London medical institution and to fund research on leprosy in India. Damien’s example inspired the creation of several other organizations devoted to the study and treatment of leprosy, from the U.S. and Belgium to Congo and Korea.

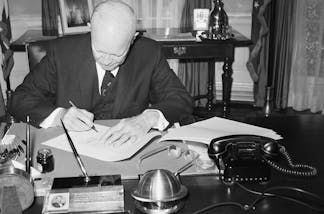

In 1967, the French journalist and humanitarian Raoul Follereau presented the pope with a petition signed by almost 33,000 leprosy patients, calling for the beatification of Father Damien. In 1977, Pope Paul VI declared Damien “venerable,” the first step toward canonization – which eventually occurred in 2009, under Pope Benedict XVI.

–

From leprosy to HIV/AIDS

But how did the patron saint of people living with leprosy become, informally, a patron saint of people living with HIV and AIDS? Given the Catholic Church’s traditional stances against homosexuality, condoms and extramarital sex, the notion can seem paradoxical.

Comparisons between the two diseases were made from the early days of the AIDS crisis: Both were considered mysterious and frightening and severely stigmatized, with sufferers often viewed as “dirty” or “sinful.” Many caregivers were afraid to even touch AIDS patients.

Invoking Father Damien’s example became a way for religious organizations to legitimize their HIV/AIDS outreach in the eyes of the church and to emphasize their concern for patients’ social stigma – even if the Catholic Church itself was helping to perpetrate that stigma, and arguably the disease itself.

In 2003, for example, Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo, president of the Pontifical Council for the Family, wrote that “the use of condoms goes against human dignity. Condoms change the beautiful act of love into a selfish search for pleasure – while rejecting responsibility. Condoms do not guarantee protection against HIV/AIDS. Condoms may even be one of the main reasons for the spread of HIV/AIDS.”

Even in 2009, the year Damien was canonized, Pope Benedict remarked that the AIDS epidemic “cannot be overcome through the distribution of condoms; on the contrary, they increase it” – an attitude out of touch with most U.S. Catholics’ views, not to mention medical science. The pope’s statement provoked such outrage that the Belgian Parliament even condemned it.

But many in the Catholic Church responded to the AIDS crisis with empathy. In 1985, for example – just a few years after the disease had been identified – the New York Archdiocese opened a treatment facility at St. Clare’s Hospital, the state’s first specialized AIDS unit.

A number of ministries turned to Father Damien as inspiration for AIDS-related work, years before the church officially made him a saint. Likely the oldest is Damien Ministries, founded in 1987 “to serve the poorest of the poor living with HIV and AIDS, as inspired by the life of the Blessed Father Damien.” The Washington, D.C.-based ministry adopted a solidarity approach modeled after Damien’s ministry on Molokai, citing parallels between leprosy and HIV/AIDS.

Other Damien-inspired organizations include the Albany Damien Center, the Damien Center of Indiana – founded as a collaboration between Catholics and Episcopalians – and St. Damien Hospital in Haiti.

A tapestry depicting Father Damien, born Jozef De Veuster, hangs from the St. Peter Basilica facade during a canonization ceremony at the Vatican. AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino

Damien serves as what religion historian Robert Orsi calls an “articulatory pivot point”: a way people – HIV/AIDS patients, in this case – can use their faith to reshape their experience and gain agency, even as that same religion stigmatizes them as powerless “others.”

As a canonized saint, Damien is embraced by the highest levels of the church. Yet as a man who embraced those the rest of society had rejected, joining them and even dying for them, he also represents people at the margins.

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 145,700 academics and researchers from 4,365 institutions.