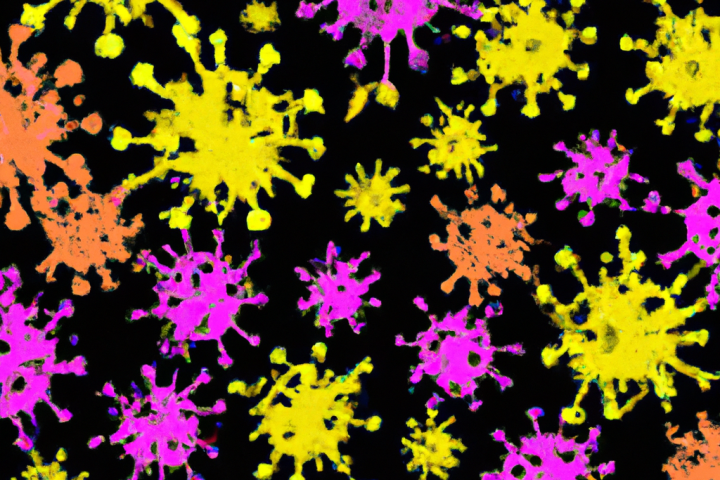

While patterns of extinction rise and fall over time, it’s generally accepted that there are five major outliers where more than 70% of life on Earth was wiped out. The first occurred about 450 million years ago at the end of the Ordovician period, wiping out up to 85% of all species alive at the time. The worst came at the end of the Permian, when up to 96% of all life died out. And the most recent occurred 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous, which famously killed off the dinosaurs.

But in the new study, scientists at UC Riverside and Virginia Tech have found evidence of another mass extinction event that took place about 100 million years earlier than the currently accepted first. This places it during the Ediacaran period about 550 million years ago, which is when complex multicellular life really took off for the first time.

Fossil records from this time are murky for a number of reasons. For one, the creatures that lived then were largely soft-bodied and so didn’t fossilize too well. Plus, the sheer amount of time that’s passed since then means that many Ediacaran fossils will be very deep down or will have been destroyed.

That makes it hard to detect the hallmarks of a mass extinction event, but the record does seem to show a drop in diversity of life from the middle to late Ediacaran. But whether this is a sampling bias, a lack of preservation, or an extinction event has been tricky to determine.

So for the new study, the researchers assembled a database of almost all known Ediacaran animals from around the world, and across the tens of millions of years of the period. They examined when these creatures lived and disappeared, as well as their environments, body sizes and shapes, diets, habits and whether they could move around or not.

In doing so, the team found that around 80% of the animals alive during the middle Ediacaran had gone extinct by the late Ediacaran. The specific modes of preservation and material deposits didn’t change in that time, which the researchers say is an indication that it wasn’t a sampling bias.

“We can see the animals’ spatial distribution over time, so we know they didn’t just move elsewhere or get eaten – they died out,” said Chenyi Tu, co-author of the study. “We’ve shown a true decrease in the abundance of organisms.”

The researchers also think they have evidence for what caused the extinction event. Geological records showed signs of a decline in ocean oxygen levels around that time, and interestingly, the animals that did survive seemed to be those adapted for low-oxygen life. This is measured by a creature’s ratio of surface area to volume.

“If an organism has a higher ratio, it can get more nutrients, and the bodies of the animals that did live into the next era were adapted in this way,” said Heather McCandless, co-author of the study.

The research was published in the journal PNAS.

Source: UC Riverside

–