2023 Jan 13

–

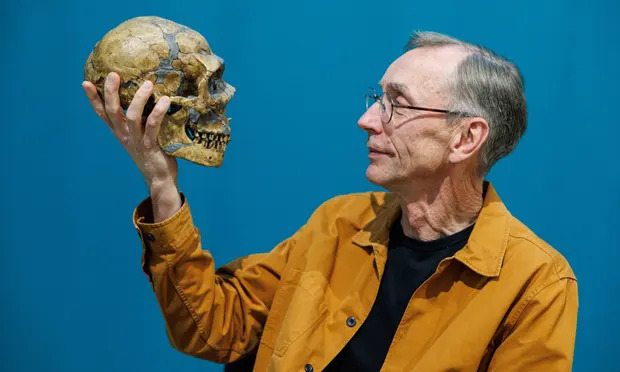

A greyish neanderthal skeleton stands at the door of Svante Pääbo’s office, acting like a doorman to check up on his visitors, who have grown considerably in number since it was announced he was to receive a Nobel prize. It clutches a white party balloon in its left hand and is missing its right lower arm.

“Unfortunately my son broke it off once,” says Pääbo with a chuckle, patting the skeleton’s head.

On the day the Guardian visits, the Swedish geneticist is still reeling from the shock of having been chosen as Nobel laureate for Medicine or physiology (the prize straddles both fields) in October. A bottle of champagne stands on his desk along with messages of congratulations from friends and colleagues. Over coffee and shortbread in a rare interview, he admits: “It’s a bit of a burden, to be honest, all the attention I’ve been getting. But it’s a pleasant burden, and one for which I know I can’t expect much sympathy.”

–

At the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in the eastern German city of Leipzig, founded by the Swedish scientist 25 years ago, where he has installed a climbing wall in the foyer and a sauna on the roof, his co-workers did their best to stop the award from going to his head.

“They gave me champagne and then they threw me in the pond outside – it’s something of a tradition here – it was rather cold, but they were very nice and removed my glasses and took my phone away beforehand.”

To be fair to them, he says, “they were in a euphoric mood. This is as much their prize as mine and is really the first time something in our field has ever been awarded a Nobel prize.”

Pääbo is credited with rewriting the story of humanity by accomplishing what was once deemed impossible – sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal through the extraction of ancient DNA. He spawned the scientific field of paleogenetics, and has revolutionised our understanding of the past with his discovery of a previously unknown hominim (the term refers to modern and extinct humans, as well as our immediate ancestors), Denisova, and establishing that gene transfer between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had taken place about 70,000 years ago.

One of the first of many surprises in his research was to find out that the genetic differences between Neanderthals and all modern humans (amounting to about 30,000) are far less than the differences between two random human beings alive today – around 3 million. “Our job is to find out which of those 30,000 are most important, because they tell us what makes us uniquely human,” he says.

At least half of the Neanderthal genome – probably as much as 60 to 70% of it, Pääbo believes – is to be found in living humans. “Which means that in effect Neanderthals are not really extinct at all, they are in us.”

His obsession started as something of a hobby, Pääbo explains. “As a kid I’d wanted to be an archaeologist, and Egyptologist. I made secret private excavations in the forests in Sweden where I lived.” A trip to Egypt with his mother, who had a huge influence on his life, proved crucial. But when he started studying Egyptology he realized he had a “far too romantic idea of it”. So he switched to medicine and later did a PhD in molecular biology.

“I realised there were methods emerging whereby you could take DNA from an organism, multiply the bacteria and study it. It seemed to me not so far away from being able to do this with Egyptian mummies.”

He secretly started experiments at weekends, scared to share what he thought might be considered rather loony ambitions with his thesis adviser, but who, when Pääbo came up with results, ended up being very encouraging.

“It turned out it was possible to extract DNA from ancient samples, but they was massively contaminated, including with microorganisms and other sources of DNA.” So he turned his efforts to developing more sophisticated extraction methods, leading after years of trial and error, to being able to tease the DNA out of Neanderthals, Denisovans and other hominims.

Behind the scientific success story is also one of considerable personal challenge. “My father had two families and we were the undisclosed one, the other was the official one. My father would show up on Saturdays, have coffee or lunch with me and my mum and then disappear again.”

His mother, Karin, who died in 2013, would have been “proud and thrilled” about his prize, he says. She came to Sweden from Estonia in 1944, escaping the Soviet invasion, and overcame linguistic and financial barriers to become a chemist.

The fact that his father, Sune Bergström, a biochemist, was himself awarded the Nobel prize (also for physiology or medicine) in 1982 for his work on prostaglandins, had little influence on Pääbo’s own scientific path he says. “Only to the extent that my mother met him through her work. It was rather her great fascination with science that was transmitted to me. She hugely encouraged my curiosity and supported me when I changed from medicine to natural sciences. She was by far the greater influence.”

When his father received the award in Stockholm, he was a graduate student in Uppsala and followed the ceremony on television.

“I had a different surname to him and only very few people even knew we were related,” he says. It wasn’t so much having to keep his famous father secret from his colleagues that was painful to him, “rather that his other, ‘official’ son knew nothing about us. We had several intense rows about it. I even threatened to seek out his family and explain it to them. So my father said he would tell them, but it never came to that,” he recalls.

In 2014 he told the Observer his father’s other family found out when Bergström died in 2005. “It was only then my half-brother learned about me. Fortunately he adjusted and we get on all right,” Pääbo said.

Pääbo says the strongest force guiding him is his own curiosity, comparing his research to that of an archaeologist, “only that our excavations are in genomes.”

The information he and his team has retrieved gives us a whole new reference point for understanding our evolution, which potentially has a multitude of benefits “including enabling a greater understanding as to what makes us uniquely human and how evolution influences our biology today,” he says.

It was a shock, Pääbo stresses, to discover that people who have inherited a certain Neanderthal chromosome variant, were twice as likely to die of Covid if infected.

“Based on the official coronavirus mortality statistics and the prevalence of the risk variant, we can estimate that this Neanderthal variant is responsible for 1.1 million extra coronavirus deaths,” he says. The variant is most commonly found in southern Asia.

Another surprising discovery relates to pain perception. Using data from the UK’s biobank – the world’s largest biomedical database which contains the genetic information of around half a million of the country’s citizens – Pääbo was able to establish that people with a specific Neanderthal variant are more likely to feel pain and to therefore age quicker. “It’s maybe time to rethink our idea of Neanderthals as brutish individuals,” Pääbo quips. “Maybe they were actually quite sensitive.”

Other extensive research projects involve everything from HIV susceptibility to progesterone receptors and their influence on pre-term babies and miscarriages. Here, possessing a Neanderthal variant has been shown to protect against miscarriage.

“Today in the public domain there are three high quality Neanderthal genomes, and I can tell you that there are more on the way,” the 67-year-old says, adding he has, for now, shelved his plans for retirement.

–

Topics