Study suggests antimicrobial used to promote livestock growth breeds bacteria more resistant to our natural defenses.

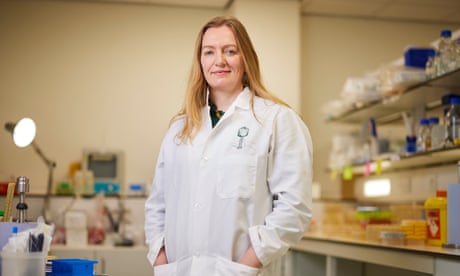

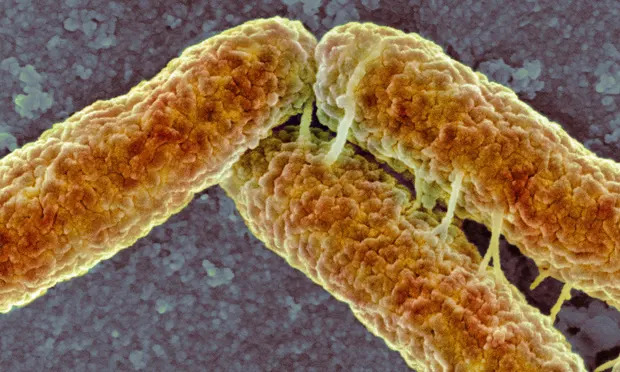

A strain of E. coli more likely to evade our immune system’s first line of defense emerged as a result of using colistin as a growth promoter on pigs and chickens. Photograph: Science Photo Library/Alam–

A strain of E. coli more likely to evade our immune system’s first line of defense emerged as a result of using colistin as a growth promoter on pigs and chickens. Photograph: Science Photo Library/Alam–

The blanket use of antibiotics in farming has led to the emergence of bacteria that are more resistant to the human immune system, scientists have warned.

The research suggests that the antimicrobial colistin, which was used for decades as a growth promoter on pig and chicken farms in China, resulted in the emergence of E coli strains that are more likely to evade our immune system’s first line of defense.

Although colistin is now banned as a livestock food additive in China and many other countries, the findings sound an alarm over a new and significant threat posed by the overuse of antibiotic drugs.

“This is potentially much more dangerous than resistance to antibiotics,” said Prof Craig MacLean, who led the research at the University of Oxford. “It highlights the danger of indiscriminate use of antimicrobials in agriculture. We’ve accidentally ended up compromising our own immune system to get fatter chickens.”

The findings could also have significant implications for the development of new antibiotic medicines in the same class as colistin, known as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which the scientists suggest could pose a particular risk of compromising innate immunity.

AMPs are compounds produced by most living organisms in their innate immune response, which is the first line of defense against infection. Colistin is based on a bacterial AMP – microbes use the compounds to shield themselves against competitors – but is chemically similar to some AMPs produced in the human immune system.

The extensive use of colistin in livestock from the 1980s triggered the emergence and spread of E coli bacteria carrying colistin resistance genes, which eventually prompted widespread restrictions on the drug’s use in agriculture. But the latest study suggests the same genes also allow pathogens to more readily evade AMPs that form a cornerstone of our own immune response.

In the study, E coli carrying a resistance gene, called MCR-1, were exposed to AMPs known to play important roles in innate immunity in chickens, pigs, and humans. The bacteria were also tested for their susceptibility to human blood serum.

The scientists found that E coli carrying the MCR-1 gene were at least twice as resistant to being killed by human serum. On average, the gene increased resistance to human and animal AMPs by 62% compared with bacteria that lacked the gene. The study, published in the journal eLife, also showed that the resistant E coli was twice as likely to kill moth larvae that were injected with the infection, compared with the control E coli strain.

MacLean said it was not possible to estimate how this might translate into real-world consequences, such as the risk of an E coli infection leading to sepsis and death. And the prevalence of these strains of E coli have dropped steeply since China banned the use of colistin as a growth promoter, suggesting that these genes carry other “fitness disadvantages” for the pathogens. However, the findings highlight a fundamental risk that has not yet been extensively considered.

“The danger is that if bacteria evolve resistance to [AMP-based drugs], it could also make bacteria resistant to one of the pillars of our immune system,” said MacLean.

Antimicrobial resistance poses a dire global threat – the UN has warned that as many as 10 million people a year could be dying by 2050 as a result of superbugs – and so the need for new antibiotics is pressing. There is growing interest in the potential of AMPs as drugs, and some of those in development include drugs based on human AMPs.

MacLean and colleagues are not calling for the development of such drugs to be put on hold, but say extremely careful risk assessments of the likelihood of resistance emerging and the potential consequences are required. “For AMPs, there are potentially very serious negative consequences,” he said.

Dr Jessica Blair, of the University of Birmingham, who was not involved in the study, said: “Antimicrobial peptides, including colistin, have been heralded as a potential part of the solution to the rise of multidrug-resistant infections. This study, however, suggests that resistance to these antimicrobials may have unintended consequences on the ability of pathogens to cause infection and survive within the host.”

Dr George Tegos, of Mohawk Valley Health System in New York, said that broad conclusions about the potential risks of AMPs could not be drawn from a single study, but added that the findings “raise concerns that are reasonable and make sense”.

Cóilín Nunan, an adviser to the Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics, who was not involved in the study, said: “This new study shows that colistin resistance is probably even more dangerous than previously thought … It is also remarkable that the British government is still opposed to banning preventative mass medication of intensively farmed animals with antibiotics, even though the EU banned such use over a year ago.”

Topics

Most viewed

- –