Among other potential applications, the powder could be used by backpackers collecting drinking water on the go. Depositphotos

Among other potential applications, the powder could be used by backpackers collecting drinking water on the go. Depositphotos

–

Developed by scientists from Stanford University and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory [Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Menlo Park, CA], the powder is made up of nanoflakes of aluminum oxide, molybdenum sulfide, copper and iron oxide. All of these substances are readily available and inexpensive, plus only a small amount of the powder is required to treat a relatively large quantity of water.

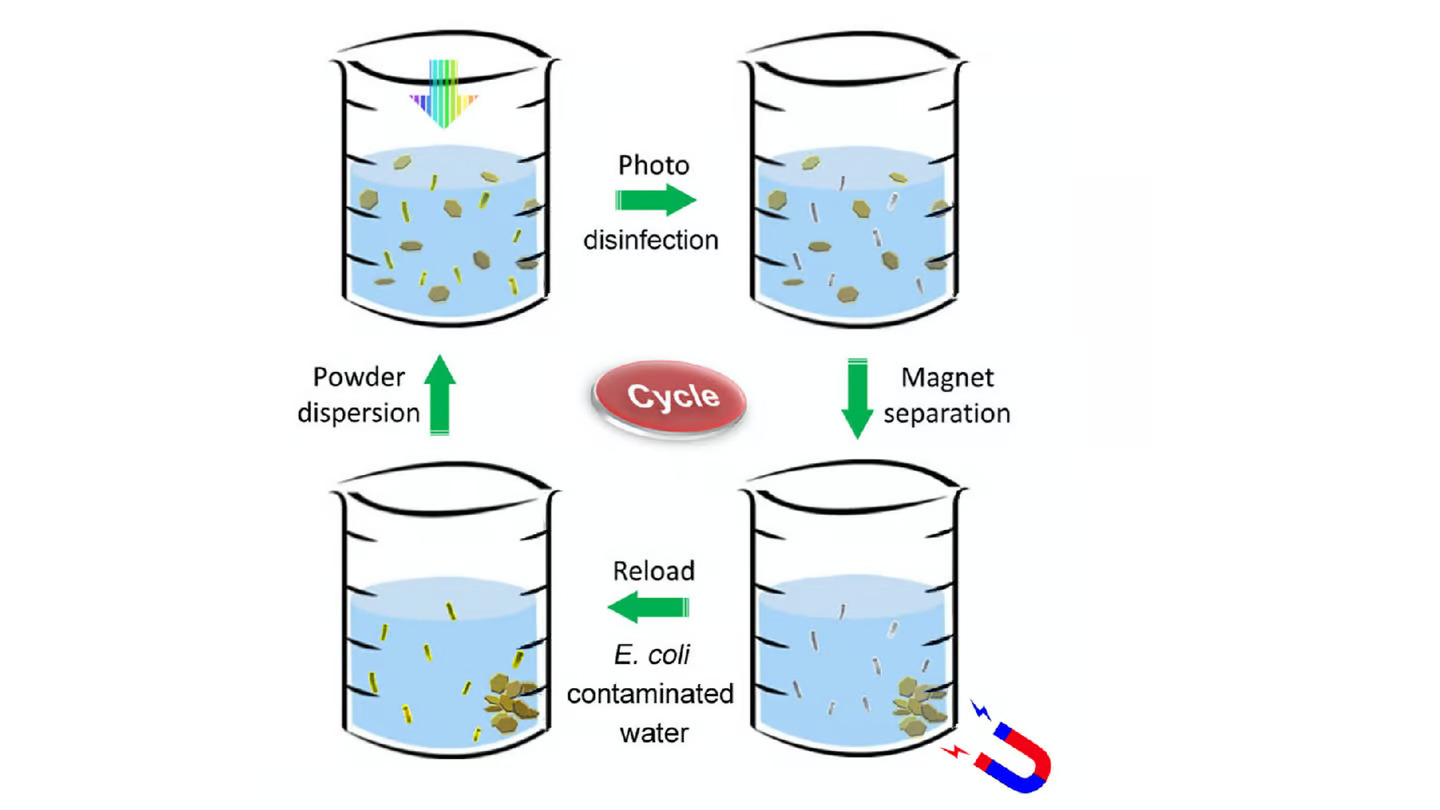

Users start by stirring some of the powder into tainted water contained in a bottle or other transparent vessel, after which they leave it exposed to direct sunlight.

The molybdenum sulfide and copper absorb photons from the light, then act as a semiconductor/metal junction which allows the photons to release electrons. Those electrons are then free to react with the water, producing hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals which kill bacteria by rupturing their protective outer membranes.

Once the purification process is complete, any leftover hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals quickly break down into water and oxygen, leaving the water safe to drink. And because of their iron oxide content, the nanoflakes can be retrieved for reuse by swirling a magnet through the water.

In a test of the technology, a small amount of the powder was added to a 200-ml (6.8-oz) beaker of room-temperature [water] that was contaminated with approximately one million E. coli bacteria per milliliter. After the water had been left in natural sunlight for just 60 seconds, no live bacteria could be detected. What’s more, the powder was able to be reused for 30 more treatments.

It is hoped that the technology could ultimately be utilized in impoverished regions which lack water purification infrastructure, or by people such as backpackers who collect water from streams and lakes. The powder might even find use at water treatment plants, which currently use artificial ultraviolet light to kill bacteria.

“During the day the plant can use visible sunlight, which would work much faster than UV and would probably save energy,” said Stanford’s Prof. Yi Cui, senior author of a paper on the research. “The nanoflakes are fairly easy to make and can be rapidly scaled up by the ton.”

The paper was recently published in the journal Nature Water.

Source: Stanford University

–