![]() By PhD Candidate in Behavioural Science, Durham University

By PhD Candidate in Behavioural Science, Durham University

![]() and by Professor of Behavioural Science, Durham University

and by Professor of Behavioural Science, Durham University

![]() and by Associate Professor of Behavioural Science, Durham University

and by Associate Professor of Behavioural Science, Durham University

Published: 2023 Oct 31

–

There was a time when smoking cigarettes was not only a normal thing to do, it was actually encouraged by doctors. Eventually, the evidence caught up.

A similar thing has happened with meat over the last couple of decades. Recent statements by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and World Health Organization (WHO) have confirmed that meat damages human health and the planet. But as with tobacco in the 1960s and 70s, this scientific knowledge has taken time to filter into consumer behavior.

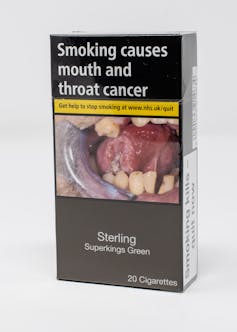

Messages such as “smoking kills” and “smoking causes blindness” alongside a graphic image have been legally required on all tobacco products in the UK since 2008. These warning labels helped reduce the number of smokers nationally. Could something similar work to reduce meat consumption? And if so, what is the best thing to warn people about?

–

In a new study, we found that graphic warning labels cut the selection of meat meals by 7%-10% when they described the consequences of meat-eating for health, disease epidemics and climate change.

What’s worth warning about?

Warning labels on meat packaging or menus could highlight evidence that a relatively high intake of meat products increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and according to one study, dementia. There is also evidence of red and processed meat consumption leading to a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes, obesity and multiple cancers.

Or, these labels could warn people that meat farming dramatically increases the risk of a pandemic. Outbreaks of zoonotic diseases (which jump from animals to humans, such as COVID-19 or swine flu) are more likely to emerge where animals are kept in extremely close contact. And as farms expand into wild land, species deprived of habitats migrate into towns and cities where encounters with people are more likely.

–

Labels on meat products and menus could also warn people of the environmental damage wrought by meat consumption. Livestock farming is estimated to be responsible for up to 15% of all greenhouse gas emissions arising from human activity. The Committee on Climate Change, which advises the UK government, has said meat consumption should fall by 20% by 2030 and 35% by 2050 to reach the country’s net zero target.

Testing the labels

In a recent study, we asked 1,001 UK meat-eaters to choose between four options for 20 meals in an online questionnaire. Participants had to confirm their preference by clicking an image of a meat, fish, vegetarian or vegan option for meals including burgers, curries, lasagna and pasta bakes.

To gauge the impact of graphic warning labels on the number of people opting for meat, we split participants into four groups. One group saw a warning label beneath the meat option depicting a deforested area and the phrase “eating meat contributes to climate change”. Another group saw the meat option labelled with an image of a man having a heart attack and the text “eating meat contributes to poor health”. A third group saw a label below the meat option depicting caged animals in a wet market, alongside “eating meat contributes to pandemics”. The final group saw the four meal options with no labels.

When no warning label was presented, participants chose the meat options about two out of three times (64%). This figure dropped to 54% with the pandemic warning labels, 55% with the health warning labels and 57% with the climate warning labels.

–

Government interventions to encourage people to eat less meat can be controversial, so the question remains as to which label might be the most suitable for a public awareness campaign. In follow-up questions, participants indicated that they did not oppose climate warning labels on meat, but were less supportive of labels referring to the health and pandemic risks of meat consumption.

While more research is needed to replicate and confirm these findings, we now have some evidence to suggest that introducing climate warning labels may be both effective at affecting meal choices and relatively acceptable to the public.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

–

Authors Disclosure Statement

Jack Hughes is affiliated with the Green Party.

Mario Weick and Milica Vasiljevic do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Durham University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

–

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 173,200 academics and researchers from 4,777 institutions.

Comments are open on selected articles and must comply with our community standards.