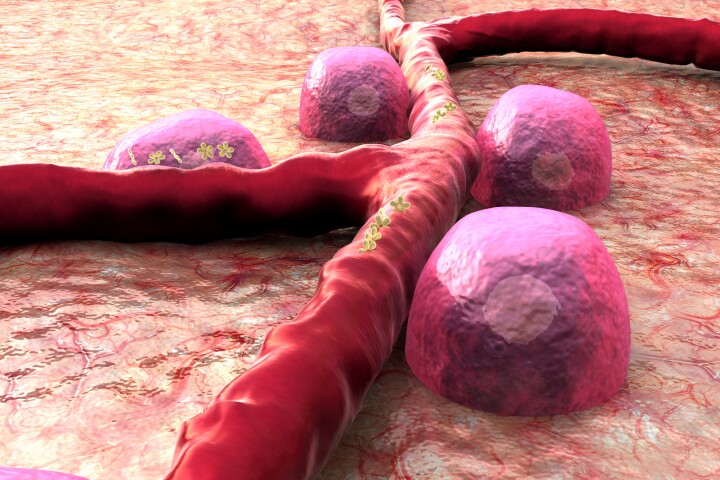

Plants with the altered microbiome proved to be more resistant to harmful bacteria. Depositphotos –

Plants with the altered microbiome proved to be more resistant to harmful bacteria. Depositphotos –

In the initial phase of the study, the researchers identified a gene in rice plants which is responsible for their production of lignin (a biopolymer that makes up plants’ cell walls).

The scientists suspected that this gene also affects the makeup of rice plants’ microbiome, so they deactivated the gene to see what would happen. Sure enough, populations of beneficial Pseudomonadales bacteria in the microbiome dropped when this was done.

Next, the researchers genetically altered the gene to make it overproduce a specific metabolite during the lignin-synthesis process. As was suspected would happen, Pseudomonadales populations climbed to higher than normal levels as a result.

When the altered plants were subsequently exposed to Xanthomonas oryzae – a harmful bacteria which causes a disease known as leaf blight – they were significantly more resistant to the pathogen than a control group of unmodified rice plants.

“This breakthrough could reduce reliance on pesticides, which are harmful to the environment. We’ve achieved this in rice crops, but the framework we’ve created could be applied to other plants and unlock other opportunities to improve their microbiome,” said the University of Southampton’s Assoc. Prof. Tomislav Cernava. “For example, microbes that increase nutrient provision to crops could reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers.”

A paper on the study – which also involved scientists from China, Germany and Austria – was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: University of Southampton

–