Zophobas atratus worms – more accurately, the larvae of the darkling beetle – are popular insect snacks in many countries where they are often bred and sold for pet reptile food. But while they’re known as superworms for their protein-rich nutritional value, their true superpower may be found in the makeup of their gut bacteria.

In this new study, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) researchers built on previous research into the microbiome of these hardy mealworms to construct a scalable copy of the organism’s special gut environment, which they believe could be capable of sustainably processing a significant amount of common plastics.

While scientists have known of the worm’s appetite for plastics for some time, the problem – as with a lot of biotechnology – is getting it suitable for real-world application. The team behind this ‘super gut’ may have cracked the code. And very few worms are harmed in the process.

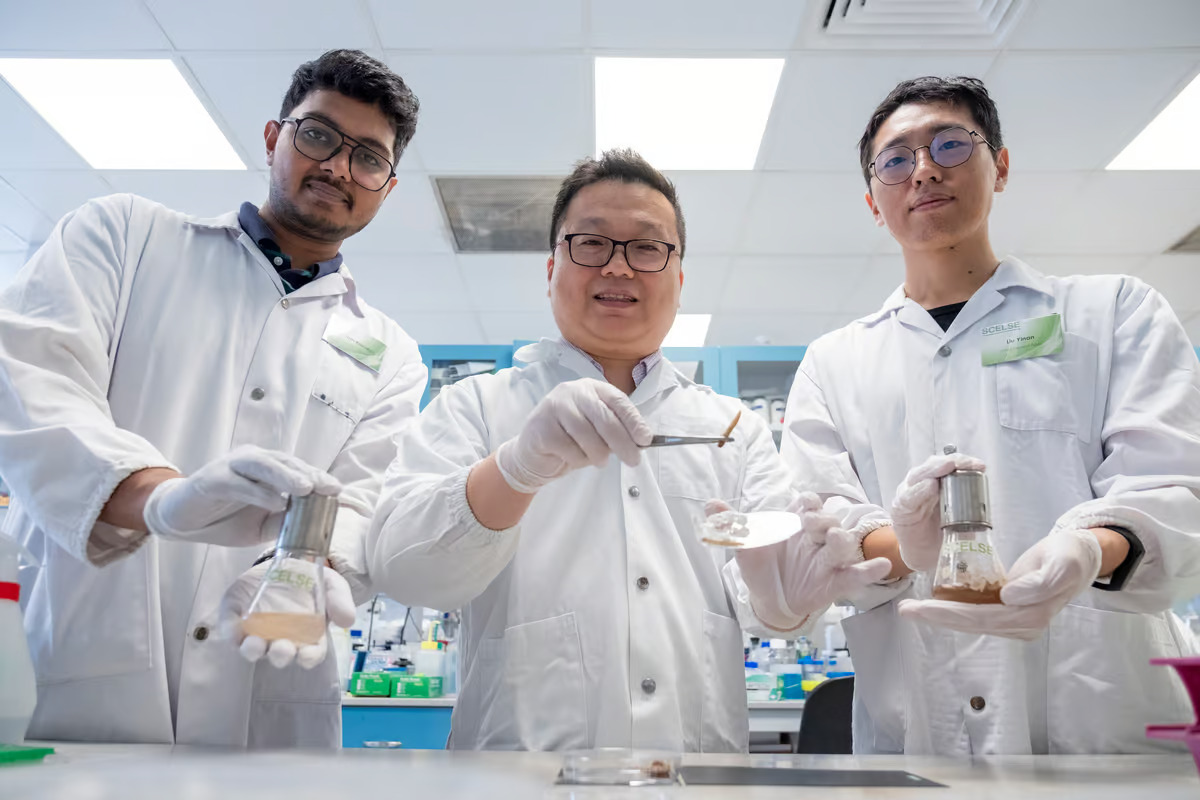

“A single worm can only consume about a couple of milligrams of plastic in its lifetime, so imagine the number of worms that would be needed if we were to rely on them to process our plastic waste,” said Cao Bin, associate professor at NTU. “Our method eliminates this need by removing the worm from the equation. We focus on boosting the useful microbes in the worm gut and building an artificial ‘worm gut’ that can efficiently break down plastics.”

The team began by feeding three sets of worms three different diets of common plastics – high-density polyethylene (HDPE), which is notoriously difficult to break down, polypropylene (PP) and polystyrene (PS) for 30 days. (A lucky control group was served oatmeal.)

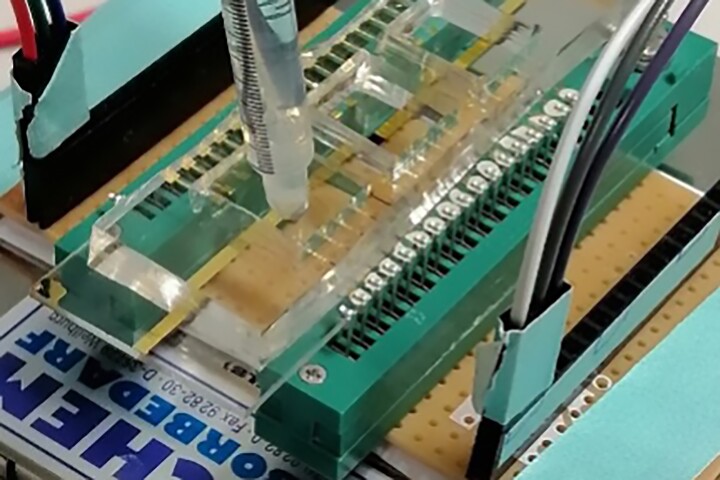

The scientists then extracted the microbiomes from the plastic-munching worms’ guts and incubated them in flasks filled with synthetic nutrients and the three plastics, letting them develop into an artificial gut over six weeks.

What they found was that the lab-grown guts, compared to the control group of worms, had developed far more plastic-degrading bacteria, and each showed superior efficiency with the specific material it had been fed on.

“Our study represents the first reported successful attempt to develop plastic-associated bacterial communities from gut microbiomes of plastic-fed worms,” said first author of the study Dr Liu Yinan. “Through exposing the gut microbiomes to specific conditions, we were able to boost the abundance of plastic-degrading bacteria present in our artificial ‘worm gut,’ suggesting that our method is stable and replicable at scale.”

While proof of concept, the researchers don’t see a barrier in being able to grow this artificial ‘super gut’ on a much larger scale and for it to be tailored to treat specific materials. They’re now looking at the molecular biology behind the worm’s hardy gut processes, hoping to more easily engineer bacterial communities that break down plastics for commercial use.

The study was published in the journal Environment International.

Source: Nanyang Technological University, Singapore View gallery – 3 images

–