The openVertebrate (oVert) project allows free access to images of over 13,000 vertebrates. Florida Museum of Natural History View 7 Images –

The openVertebrate (oVert) project allows free access to images of over 13,000 vertebrates. Florida Museum of Natural History View 7 Images –

More than a research project, oVert was a collaboration between like-minded specialists across 25 institutions whose sole objective was to add value to museum collections by making them more widely available. Importantly, these images provide an insight that would only otherwise be obtained by destructive dissection and tissue sampling.

“Museums are constantly engaged in a balancing act,” said David Blackburn, the project’s lead principal investigator and curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum. “You want to protect specimens, but you also want to have people use them. oVert is a way of reducing the wear and tear on samples while also increasing access, and it’s the logical next step in the mission of museum collections.”

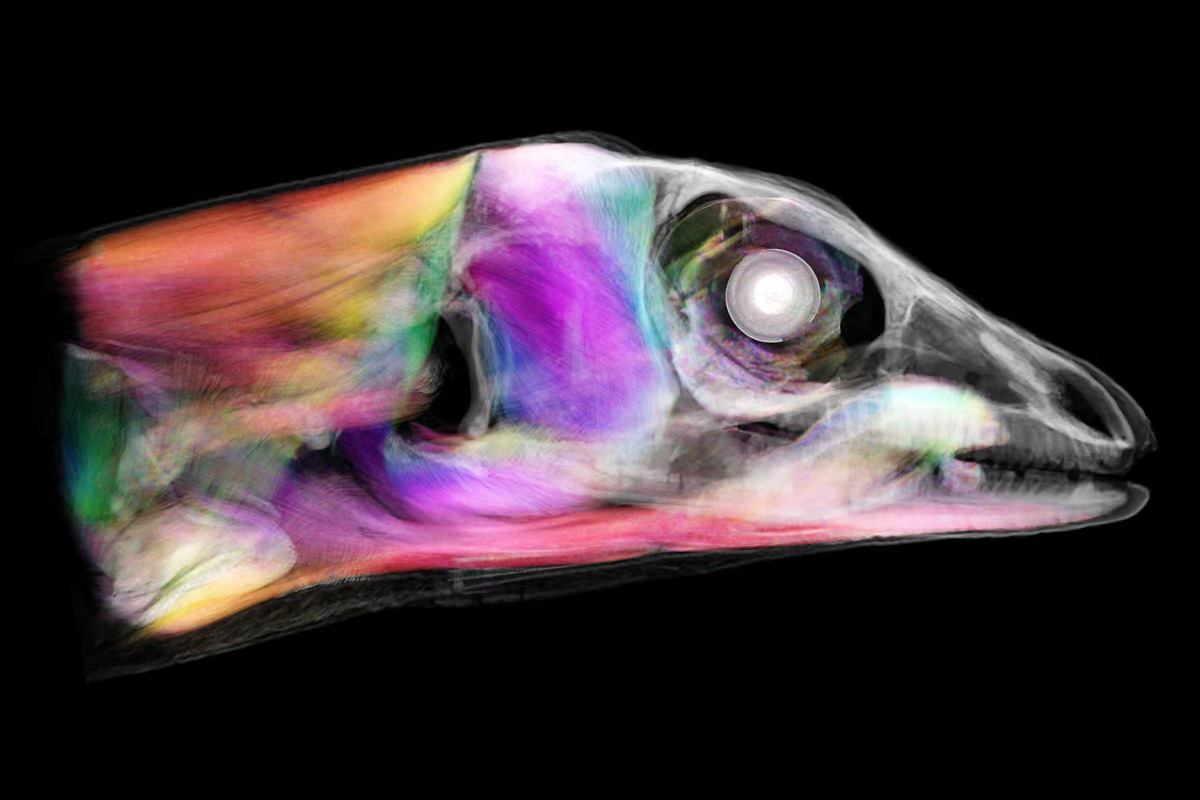

Over the course of six years, project members took CT scans of more than half the classes, or genera, of all amphibians, reptiles, fishes, birds, and mammals, rendering models that provide an intimate look at the creatures, inside and out.

Dibs on not scanning the humpback whale! Oh, wait. A partnering grant to the Idaho Museum of Natural History was used to generate the whale’s digital model. Obviously too big to fit in a CT scanner, researchers painstakingly took the animal’s skeleton apart piece by piece, created models of each bone, and then reassembled it physically and digitally.

The oVert project has already led to some fascinating insights into the natural world. For example, armadillos were thought to be the only living mammals with tails covered with an internal coat of bony plates called osteoderms. Nope. In 2023, Edward Stanley, co-principal investigator of the project, was performing routine scanning of spiny mice and found that they do, too.

“All sorts of things jump out at you when you’re scanning,” said Stanley. “I study osteoderms, and through kismet or fate, I happened to be the one scanning those particular specimens on that particular day and noticed something strange about their tails on the X-ray. That happens all the time. We’ve found all sorts of strange, unexpected things.”

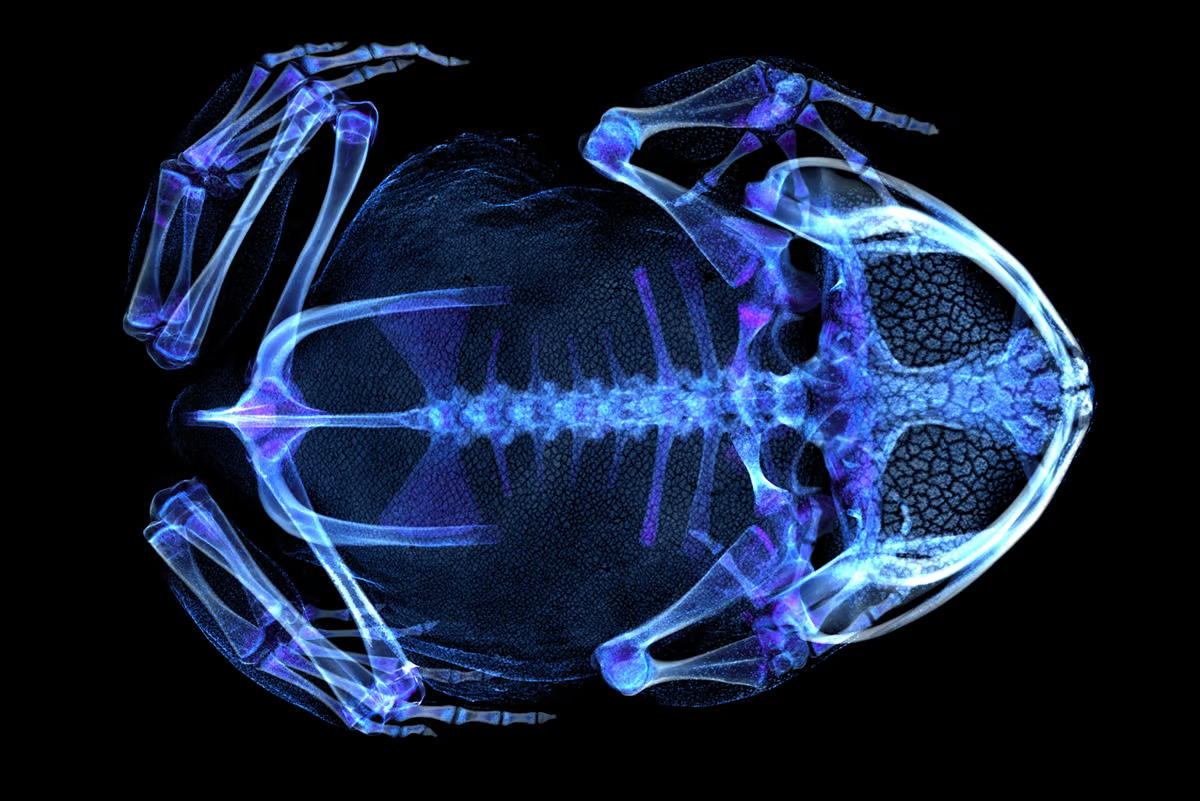

Definitely falling into the strange category was the discovery, through a study of more than 500 oVert specimens, that frogs have lost and regained teeth more than 20 times throughout their evolutionary history.

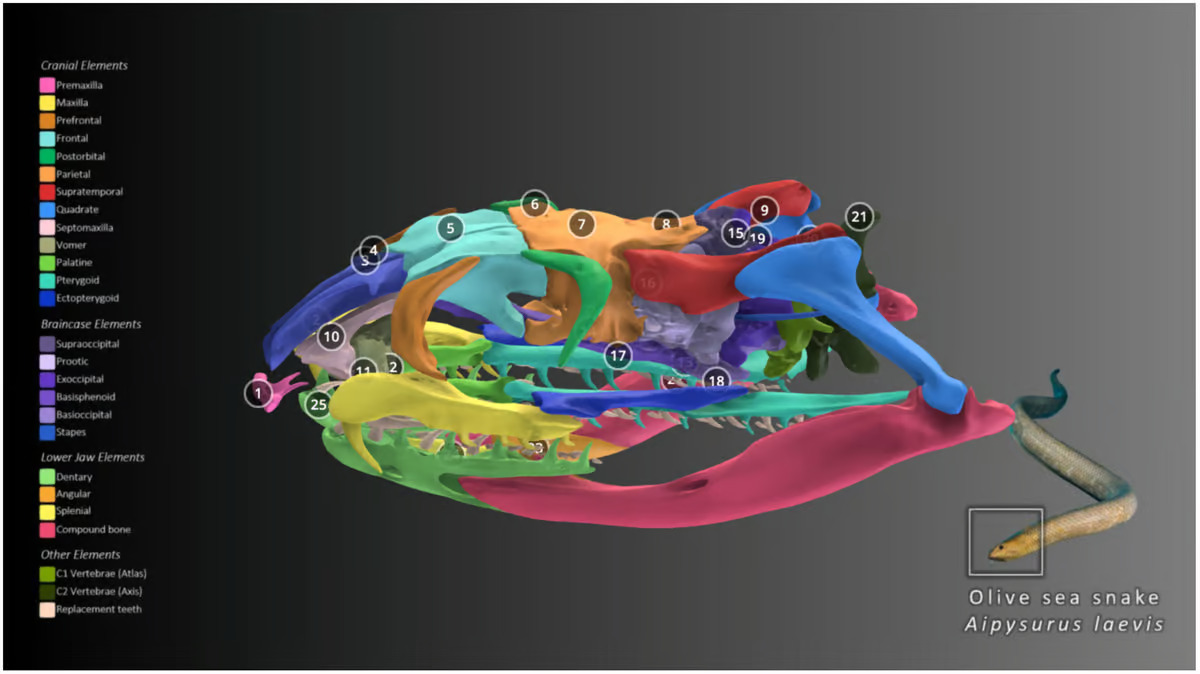

For a working example of the incredible detail and information contained in oVert’s images, head to Sketchfab to view a sample of interactive 3D models like the olive sea snake. Or go to MorphoSource to access the full oVert repository.

But scientists aren’t the only ones who have benefited from oVert. Artists have used its 3D models to create realistic animal replicas, photos of oVert specimens have been displayed as museum exhibits, and specimens have been incorporated into VR headsets so users can interact with them. There appears to be no end to oVert’s uses.

“Generating the data is just the start,” said Jaimi Gray, a postdoctoral associate at the Florida Museum who’s working on NoCTURN (Non-Clinical Tomography Users Research Network), a project developed near the end of oVert to make the best use of that project’s scans. “The aim of oVert was always to facilitate the exploration of vertebrate diversity. We’re going to keep exploring, but the goal of NoCTURN is to give people the tools to use the data, whether it’s for research, education or industry.”

If you have 30 minutes to spare, check out the full video produced by the Florida Museum, which showcases a collection of diverse oVert specimens.

–

A study presenting a summary of the oVert project was published in the journal BioScience.

–

Source: Florida Museum View gallery – 7 images

–