Anger is never a great look, especially inside your blood vessels. Depositphotos –

Anger is never a great look, especially inside your blood vessels. Depositphotos –

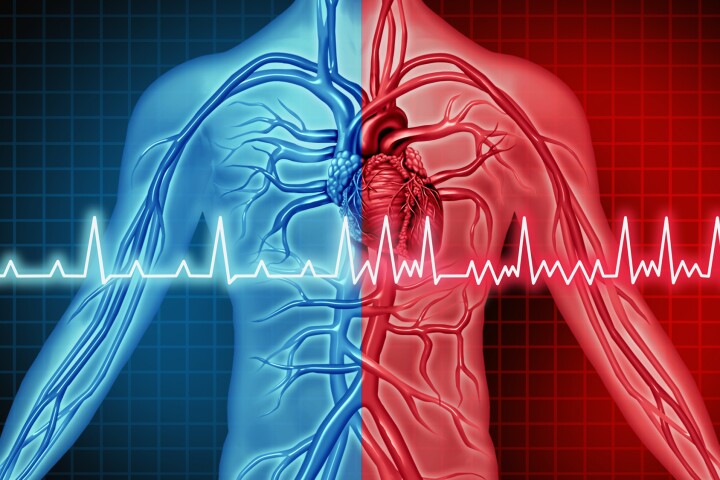

While there have been observational studies in the past linking negative emotions like anger to an increased risk of heart attacks, scientists working with the American Heart Association wanted to see if they could more precisely pin down how an experience of anger actually affects our blood vessels and the cells lining them.

So they recruited 280 healthy adults with an average age of 26 years to participate in a study in which they were asked to sit quietly and relax for 30 minutes before moving to the next step. Then, researchers took their blood pressure, heart rate, measured the dilation of their blood vessels using finger probes, and took blood samples. Next, the participants were assigned an emotional task based on their place in one of four randomly assigned groups.

One group was asked to recall a memory that made them angry, the second group was asked to recall a memory of anxiety; the third group read a batch of depressing sentences to evoke sadness; and the fourth group simply counted from zero to 100 over and over again to create an emotionally neutral state. All individuals participated in their assigned task for eight minutes.

After the tasks were completed, the same measurements from the beginning of the study were taken again at three minutes, 40 minutes, 70 minutes and 100 minutes.

The researchers found that for the participants experiencing the anger-inducing memories, their blood vessel cells were altered in such a way that dilation was impaired for up to 40 minutes after the activity. In other words, the blood vessels couldn’t relax. And previous research has linked that issue with the development of the artery-clogging disease known as atherosclerosis, which can raise someone’s risk of stroke and heart disease.

“We saw that evoking an angered state led to blood vessel dysfunction, though we don’t yet understand what may cause these changes,” said lead study author Daichi Shimbo, a professor of medicine at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “Investigation into the underlying links between anger and blood vessel dysfunction may help identify effective intervention targets for people at increased risk of cardiovascular events.”

Anxiety, sadness not as bad

Interestingly, the researchers found no negative impact to blood vessel function in the study participants who undertook the anxiety- or sadness-inducing tasks. That’s not to say those emotions don’t negatively impact heart health – just last year it was found that undergoing psychotherapy for depression could reduce cardiovascular disease risk – it’s just that this particular study didn’t reveal a physical change associated with them.

The researchers say that there are a few issues with the study including the fact that the cohort was quite young and healthy, so it’s unclear whether the results would translate to an older group who might be on medication for heart issues. The study was also carried out in the relatively peaceful setting of a lab, so it remains to be seen how our blood vessels react in real-world situations which, naturally, would be much harder to study. Still, the team says there is a lot of value in their findings.

“This study adds nicely to the growing evidence base that mental well-being can affect cardiovascular health, and that intense acute emotional states, such as anger or stress, may lead to cardiovascular events,” said Glenn Levine, writing committee chair of the AHA’s scientific statement. Levine is master clinician and professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, and chief of the cardiology section at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, both in Houston.

“This current study very eloquently shows how anger can negatively impact vascular endothelial health and function, and we know the vascular endothelium, the lining of blood vessels, is a key player in myocardial ischemia and atherosclerotic heart disease. While not all the mechanisms on how psychological states and health impact cardiovascular health have been elucidated, this study clearly takes us one step closer to defining such mechanisms.”

A paper describing the research has been published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Source: American Heart Association

–

![The Ti EDC [everyday carry] Wrench is currently on Kickstarter](https://assets.newatlas.com/dims4/default/0ba225b/2147483647/strip/true/crop/4240x2827+0+3/resize/720x480!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnewatlas-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F59%2Fb2%2F6a6fdd0348a8bfdad88bbcefec53%2Fdsc03572.jpeg)