A next-gen antibiotic kills drug-resistant bacteria while leaving good gut bacteria intact. Depositphotos –

A next-gen antibiotic kills drug-resistant bacteria while leaving good gut bacteria intact. Depositphotos –

2024 May 31

–

Antibiotic-induced disruption of the gut microbiome can compromise health and make people more susceptible to opportunistic infection by pathogens like C. difficile. The widespread rise of superbugs resistant to antibiotics further complicates their use.

“People are starting to realize that the antibiotics we’ve all been taking – that are fighting infection and, in some instances, saving our lives – also are having these deleterious effects on us,” said Paul Hergenrother, a chemistry professor at the University and the study’s corresponding author. “They’re killing our good bacteria as they treat the infection. We wanted to start thinking about the next generation of antibiotics that could be developed to kill the pathogenic bacteria and not the beneficial ones. –

”Bacteria are classified as gram-positive or gram-negative based on their cell membrane composition. Gram-positive bacteria don’t have an outer membrane, whereas gram-negative bacteria have two – external and internal – making them harder to kill. Most antibiotics kill only gram-positive or both bacterial classes (the latter are called ‘broad-spectrum’). There are few gram-negative-only antibiotics available, even though gram-negative bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics are widespread.

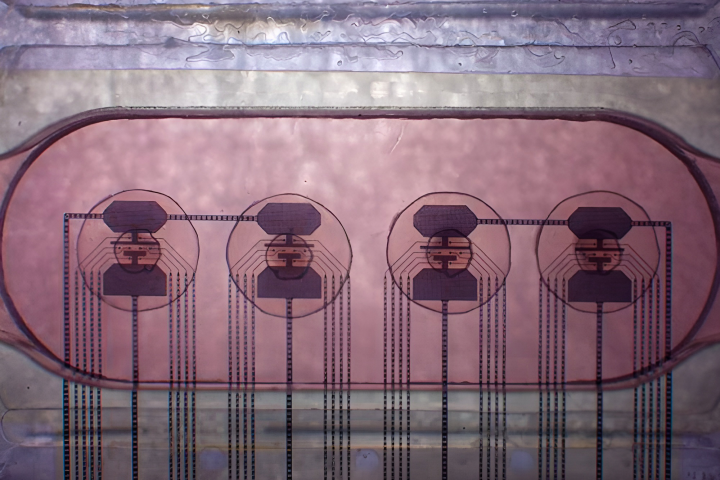

A significant percentage of the gut microbiome is composed of gram-negative bacteria, which are targeted by the few available gram-negative-only antibiotics approved for clinical use. To combat the problem of these antibiotics indiscriminately targeting gut bacteria, the researchers focused on inhibiting the Lol (localization of lipoprotein) system. Exclusive to gram-negative bacteria, the Lol system is an essential mechanism responsible for trafficking lipoproteins from the inner to the outer membrane to aid bacterial growth. The system is also genetically different in pathogenic and beneficial microbes. After trialing different compound structures, the researchers arrived at the aptly named ‘lolamicin.’

In lab tests, lolamicin at higher doses killed up to 90% of E. coli, K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics. All three are major causes of healthcare-associated (nosocomial) infections. Using mouse models of septicemia (blood poisoning, which in humans can lead to sepsis and death) and acute pneumonia, treatment with lolamicin “rescued” 100% of septicemic mice and 70% of mice with pneumonia.

Regarding the gut microbiome, while standard antibiotics amoxicillin and clindamycin dramatically changed bacterial populations in the mouse gut, reducing the numbers of several beneficial groups, lolamicin didn’t.

“Conversely, in the lolamicin treatment group, species richness was retained throughout both the treatment and recovery periods, which was analogous to the species richness detected in the vehicle control,” said the researchers.

As disturbance of the microbiome has been associated with susceptibility to C. difficile infection, the researchers infected mice with this bacteria to see how they responded. Lolamicin treatment resulted in little or no C. difficile colonization, similar to control mice. However, high-level colonization was seen in mice treated with amoxicillin or clindamycin, as they were unable to clear C. difficile.

While it sounds extremely promising, we won’t see lolamicin in the pharmacy for some time. Years of further research are needed to test the drug against other bacterial strains and determine toxicity. And, as with any new antibiotic, it will need to be assessed to determine how quickly resistance is developed.

Nonetheless, the study proves it’s possible to develop antibiotics that specifically target gram-negative bacteria – some of the most difficult bugs to kill – while sparing the good ones.

The study was published in the journal Nature.

Source: University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

–

Tags