New research has found a link between prenatal exposure to a common chemical found in plastics and autism. Depositphotos –

New research has found a link between prenatal exposure to a common chemical found in plastics and autism. Depositphotos –

The risks of exposure to bisphenol A (BPA), an industrial chemical used in plastic manufacturing and found in a wide variety of plastic products, are well-documented. Known to leach out of plastics and into the foods and beverages we consume, studies have linked BPA to health issues primarily because it mimics the structure and function of the hormone estrogen, disrupting body processes such as growth, cell repair, fetal development, energy levels, and reproduction.

It’s also been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD and autism, also referred to as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In a new study, researchers from The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health (The Florey) in Melbourne, Australia, have found a possible link between autism and exposure to BPA in the womb.

“Exposure to plastic chemicals during pregnancy has already been shown in some studies to be associated with subsequent autism in offspring,” said Professor Anne-Louise Ponsonby, head of Florey’s neuroepidemiology research group, who jointly led the study with research fellow Dr Wah Chin Boon. “Our work is important because it demonstrates one of the biological mechanisms potentially involved.”

ASD is a clinically diagnosed neurodevelopmental condition that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ASD affects about one in 100 children worldwide. Figures presented by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) this year identified about one in 36 American children have the condition, which was nearly four times more common among boys than girls. Prevalence had increased from one in 54 recorded in 2016. In 2018, Autism Spectrum Australia (Aspect) revised its autism prevalence rates from one in 100 to an estimated one in 70 Australians on the autism spectrum, around a 40% increase.

While the increased prevalence of ASD is partly attributable to greater awareness and more advanced diagnosis, potential causative factors like genetics and environment during early life and the way the two things interact remain important.

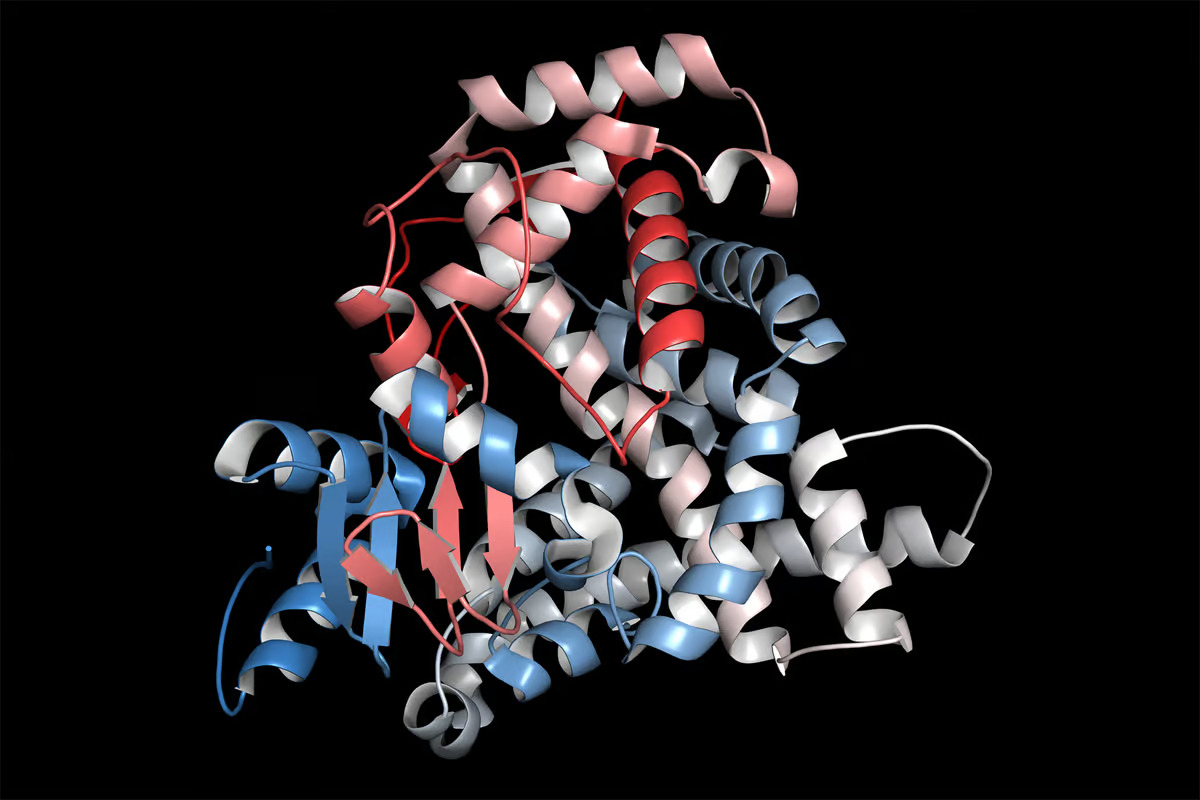

In the present study, the researchers focused on the enzyme aromatase, which converts neuroandrogens, a class of male sex hormones found in the brain, into neuroestrogens, or female sex hormones. During fetal development, aromatase expression in the brain is high in males. Studies have shown that exposure to bisphenols, of which BPA is one, can disrupt brain aromatase function.

“BPA can disrupt hormone-controlled male fetal brain development in several ways, including silencing a key enzyme, aromatase, that controls neurohormones and is especially important in fetal male brain development,” Ponsonby said. “This appears to be part of the autism puzzle.”

To examine the interplay between prenatal BPA, aromatase function and sex in relation to ASD symptoms and diagnosis, the researchers obtained data from two large cohorts: the Barwon Infant Study (BIS) in Australia and the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health Study – Mothers and Newborns (CCCEH-MN) in the US.

They found a link between the presence of BPA and ASD was particularly evident in the top fifth of boys with vulnerability to the chemical’s endocrine-disrupting properties. In other words, those with lower levels of aromatase. Boys in this group, born to mothers with higher BPA levels in their urine during late pregnancy, were 3.5 times more likely to have ASD symptoms by age two and six times more likely to have an ASD diagnosis verified by age 11 than those born to mothers with lower urinary BPA levels during pregnancy.

In both the BIS and CCCEH-MN cohorts, the evidence demonstrated that, overall, higher BPA levels were associated with epigenetic suppression of the aromatase enzyme. Epigenetic changes are DNA modifications that regulate whether genes are turned on or off. Here, the CYP19A1 gene, which provides instructions for producing aromatase.

The researchers went on to study the impact of prenatal BPA on mice.

“We found that BPA suppresses the aromatase enzyme and is associated with anatomical, neurological and behavioral changes in the male mice that may be consistent with autism spectrum disorder,” said Boon. “This is the first time a biological pathway has been identified that might help explain the connection between autism and BPA.”

The researchers’ findings understandably drew comments from others in the scientific community. Some were impressed by the researchers’ identification of the biological pathway thought to influence ASD.

“What’s really new about their results is that they were able to pin the effect to a biological pathway that is important in brain development,” said Professor Ian Rae, an expert on environmental chemicals from the School of Chemistry at the University of Melbourne. “In other words, BPA is acting as a ‘rogue’ hormone to out-compete the natural hormone that is usually involved in this pathway.”

Whereas others viewed the results with varying degrees of skepticism.

“In mice studies where the mother was treated with 50 µg/kg/day of BPA for around four days mid-pregnancy, there were changes in the number of brain cells and their structure in the male offspring,” said Dr Ian Musgrave, a senior lecturer from the School of Medicine Sciences at the University of Adelaide in Australia. “However, the majority of changes had huge overlaps between treated and untreated, and while statistically significant, it is not clear if this is biologically relevant. Furthermore, the doses were the maximum permissible, which most people are not going to be exposed to.

“What is more, the doses were given subcutaneously, which bypasses the metabolic systems BPA encounters when taken orally,” Musgrave continued. “As most human exposures are oral, and human efficiently metabolize and excrete BPA taken orally, the exposure of the mice to BPA will be higher than humans.”

Professor Elisa Hill-Yardin, Head of the Gut-Brain Axis Laboratory at RMIT University, said, “Future work to carefully measure bisphenol A levels over time during pregnancy to clarify these findings … The effects of diet may also be important in these findings.

“This is interesting research worthy of further investigation, but it’s important to understand that there are many other genetic variations that are possible contributors to autism that have similar amounts of evidence,” Hill-Yardin explained. “Ultimately, we still don’t know for sure what causes autism for most people, and a normal healthy diet and lifestyle advice should be followed during pregnancy.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: The Florey, Scimex View gallery – 3 images

–