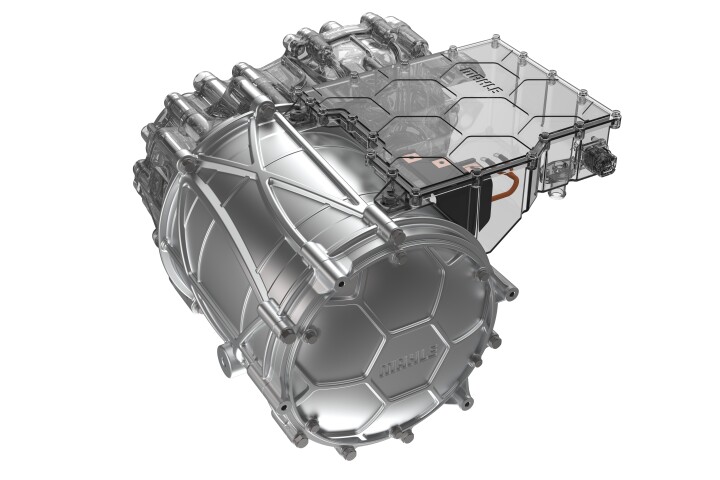

A Hypenea macrantha flower catapults its pollen onto a hummingbird’s peak. Bruce Anderson and Vinicius Brito –

A Hypenea macrantha flower catapults its pollen onto a hummingbird’s peak. Bruce Anderson and Vinicius Brito –

2024 Oct 17

–

If you were a flowering plant, wouldn’t you want your pollen to be received by a plant of your own kind? According to a new study, at least one plant may ensure that happens, by blasting “rival” pollen off of pollinating animals’ bodies.Fictional species such as triffids aside, plants can’t physically move from place to place in order to mate with one another.

That’s why flowering plants rely on either the wind or flower-feeding animals such as bees to transfer male-gamete-containing pollen from one flower to another. That ‘other’ flower can be on the same plant that the pollen came from, or on another plant of the same species.

Sometimes, a pollinating animal arriving at a flower of one species (we’ll call it Species A) may already be covered with pollen from another species (Species B). In such a case, there’s very little space for Species A’s pollen on the pollinator’s body. This means that even if the animal subsequently visits another Species A flower, it will mainly be depositing useless Species B pollen.

That’s where Hypenea macrantha enters the picture.

It’s a flowering plant endemic to Brazil, which was already known to utilize a catapult-like appendage for flinging its pollen onto the beaks of visiting hummingbirds. Until now, that mechanism was believed to serve one main purpose: to get a lot of pollen onto the bird’s beak. Recently, however, an international team of scientists began to wonder if there could be more to it than that.

Led by Prof. Bruce Anderson from Stellenbosch University in South Africa, and Prof. Vinícius Brito from the Federal University of Uberlândia in Brazil, the researchers conducted a series of experiments.

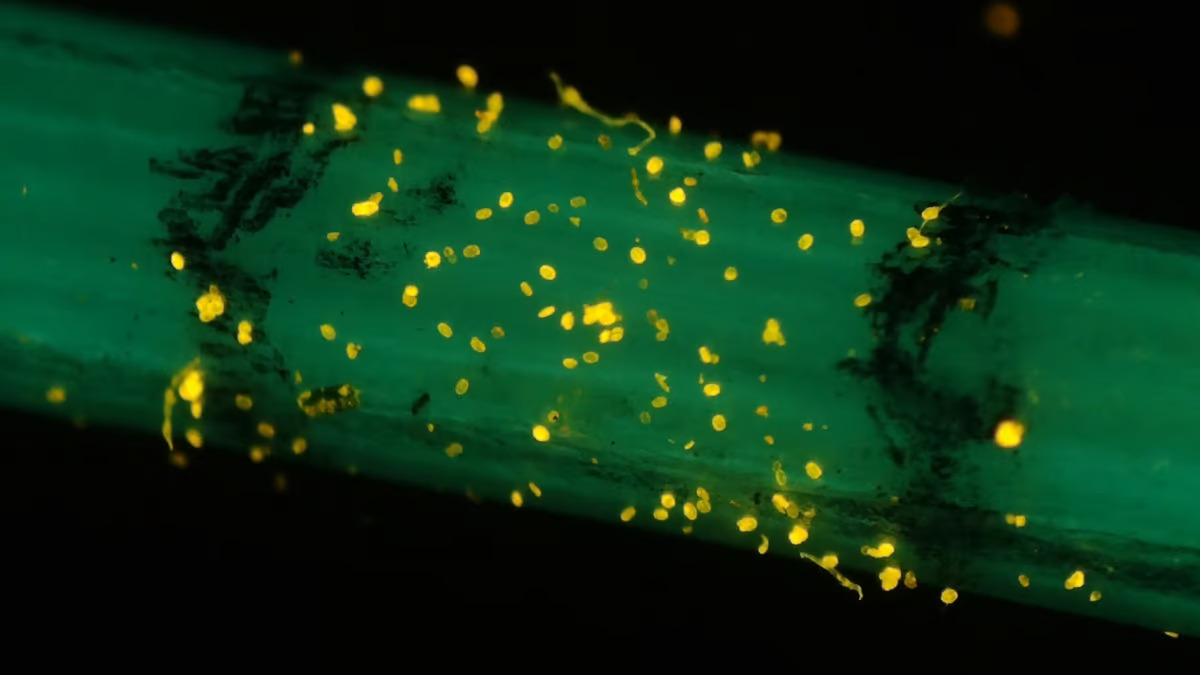

They started by depositing grains of fluorescent-tagged pollen onto the beak of a hummingbird skull, then counting the number of grains present. Next, that beak was inserted into a Hypenea macrantha flower, which responded by flinging its own pollen onto the beak.

When all of the pollen grains on the beak were subsequently counted, it was found that the greater the number of Hypenea macrantha grains that had been deposited by the flower, the fewer the number of tagged grains that remained in place.

According to the scientists, this finding suggests that the explosive force of the flower’s catapult doesn’t just serve to deposit its own pollen, but also to remove rival pollen.

“Flowers visited by hummingbirds deposit their pollen on the hummingbird bills, but there is very little place for the pollen to be deposited,” says Anderson. “Flowers have evolved a catapult mechanism where pollen is shot at the bill of the hummingbird. The force of the ballistic grains dislodges previously deposited grains from rival plants allowing the flower to place its own grains onto a cleaner bill, thus increasing its chances of reproductive success.”

A paper on the study was recently published in the journal The American Naturalist. You can see the flower in beak-blasting action, in the video below.

–

Source: Stellenbosch University via EurekAlert View gallery – 3 images

–

Tag

–