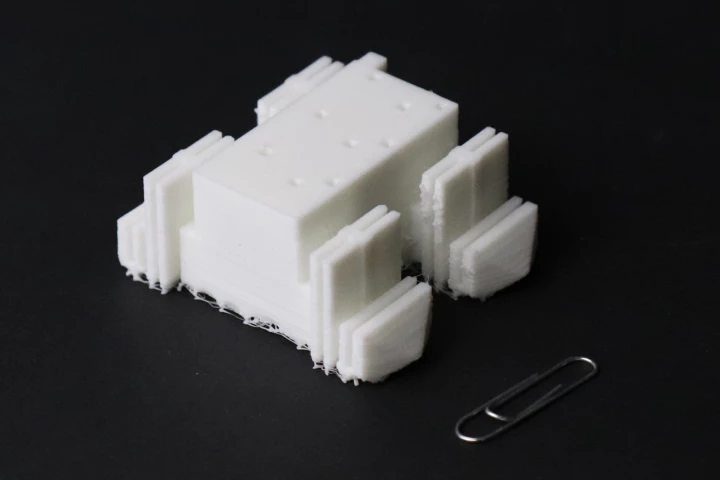

Honey from this species of Australian stingless bee has remarkable antimicrobial properties. Wikimedia Commons/Graham Wise CC BY 2.0 –

Honey from this species of Australian stingless bee has remarkable antimicrobial properties. Wikimedia Commons/Graham Wise CC BY 2.0 –

Nature knows what it’s doing, especially when it comes to producing medicinal compounds. Over millennia, native peoples have tried and tested these natural products the way nature intended. Sometimes, it takes Western medicine some time to catch up.

In a new study led by the University of Sydney, researchers investigated the antimicrobial properties of honey produced by particular native stingless bee species. This honey has been used medicinally by Indigenous Australians for thousands of years, and may be helpful in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

“Given the growing medical challenge of antimicrobial resistance, our findings suggest stingless bee honey could complement, or provide a valuable alternative to, synthetic antibiotics,” said Dr Kenya Fernandes, from the university’s School of Life and Environmental Sciences and the study’s lead and corresponding author.

There are a few native Australian stingless bee species that produce a distinct honey, known locally as “sugarbag.” While Indigenous Australians have used it for thousands of years as both a nutritious food source and a medicine to treat itchy skin and sores, there is limited research into the honey’s antimicrobial properties. The word “microbe” covers a diverse range of organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Honey’s antimicrobial activity is attributed to either peroxide activity or non-peroxide activity.

Peroxide activity comes from hydrogen peroxide, a chemical known for its ability to kill microbes. An enzyme called glucose oxidase, which bees add to nectar, turns glucose into gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide when the honey is diluted (for example, by wound moisture or saliva). Hydrogen peroxide works by damaging microbial proteins, DNA, and membranes and is effective against a wide variety of bacteria and fungi. Non-peroxide activity refers to antimicrobial effects not caused by hydrogen peroxide but due, instead, to other bioactive compounds such as phenolics and flavonoids. These compounds can disrupt cell membranes and interfere with cell metabolism, and are often more stable than peroxide activity.

While Manuka honey is a well-known example of non-peroxide activity, honey from some species of Australian stingless bees is known to have both peroxide and non-peroxide activity. In the present study, the researchers evaluated the antimicrobial activity of sugarbag honey produced by three species of stingless bees, Tetragonula carbonaria, Tetragonula hockingsi, and Austroplebeia australis. The honeys were tested against four disease-causing microbes: the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (“golden staph”) and E. coli, and the fungi Cryptococcus neoformans and Trichophyton interdigitale.

“Manuka honey from honeybees displays strong non-peroxide antimicrobial activity, which is one reason why its production has been a commercial success,” Fernandes said. “However, that is largely reliant on the source of its nectar from specific myrtle plants (Leptospermum). In contrast, the persistent antimicrobial activity of heat-treated, non-peroxide honey from stingless Australian bees across diverse locations and nectar sources suggests there is something special about these bees, rather than just nectar, that plays a critical role here.”

All of the honeys showed antimicrobial activity. The fungus T. interdigitale was the easiest to kill, and C. neoformans was the hardest. Honey produced by T. carbonaria bees was the strongest overall, especially against fungi. A. australis honey was the weakest. When the honeys were heated to destroy hydrogen peroxide, many retained strong non-peroxide antimicrobial activity. This is important as it means they’re more stable and useful in medical settings. The researchers found that, unlike regular honey, the stingless bee honeys they evaluated can slowly release hydrogen peroxide over several days, not just for a few hours. Astonishingly, some T. carbonaria honeys produced it for more than six days.

“We discovered the antimicrobial activity is consistent across all sugarbag samples tested, unlike honeybee honey, which can vary significantly based on seasonal changes and floral sources,” said study co-author Professor Dee Carter, also from the University of Sydney’s Life and Environmental Sciences School.

When the researchers looked at the makeup of the honeys, they found that they contained phenolics and flavonoids, plant compounds that’ve been shown to fight microbes and inflammation. They also found many different proteins in the honeys, including some potentially linked to immune defense. Indeed, each bee species’ honey had a different protein “fingerprint.” And, honey samples stored for 18 years still had antimicrobial power, even after the peroxide degraded, demonstrating the product’s long-term stability.

“While we have yet to test the honeys against drug-resistant bacteria specifically, the presence of multiple antimicrobial factors significantly reduces the likelihood of resistance developing,” said Fernandes.

The next step is to ensure that the sugarbag honey can be produced at the required scale, given that each stingless beehive only produces about half a liter (17 fl oz) a year.

“While the yield is small, these hives require less maintenance than traditional beehives, allowing beekeepers … [for the balance of this very interesting article please visit: https://newatlas.com/health-wellbeing/sugarbag-honey-antimicrobial-properties/]

–

The study was published in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

Source: University of Sydney

–