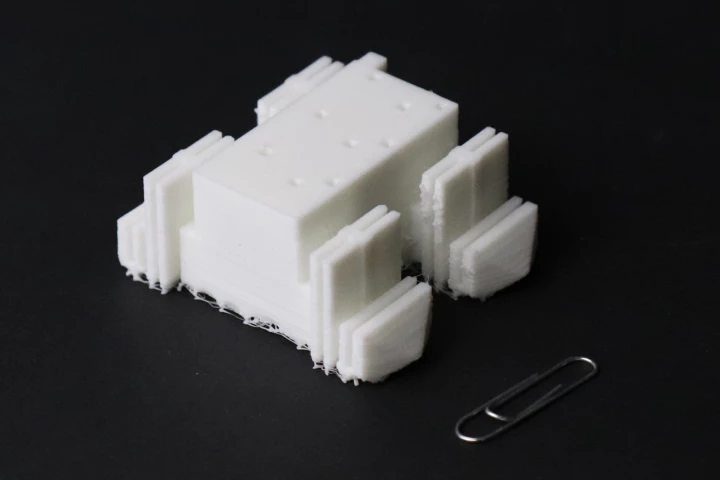

A researcher at the Jackson Laboratory working on examining biological markers to identify chronic fatigue syndrome. Jackson Laboratory –

A researcher at the Jackson Laboratory working on examining biological markers to identify chronic fatigue syndrome. Jackson Laboratory –

Technically known as myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), the condition is marked by debilitating fatigue that doesn’t go away with rest; cognitive impairment such as brain fog and difficulty focusing; sleep disturbances; and pain. While it often appears after an infection with the Epstein-Barr virus, the condition is most often a diagnosis of elimination in which doctors rule out other conditions based on self-reported patient symptoms. Because no hard-and-fast medical test exists for ME/CFS, the condition is sometimes considered more of a psychological than physical ailment.

New research from the Jackson Lab (Bar Harbor, Maine), however, has found a unique biological fingerprint of the disease in the gut microbiome, which should not only give ME/CFS patients hope that their symptoms will be taken seriously, but also open the door to new treatment options.

The new breakthrough builds on previous research that noted a link between certain immune system disruptions and ME/CFS. For this study, the scientists gathered biological data from 153 ME/CFS patients and 96 healthy patients including genetic analysis of gut microbes; metabolites in blood plasma; overall blood test results; immune cell profiles. They also gathered self-reported symptom data.

Next, they ran that data through a deep neural network model called BioMapAI. They found that based on immune cell and gut profiles from ME/CFS patients their model was able to predict the presence of the condition with 90% accuracy. The model was then given external datasets and was able to predict ME/CFS 80% of the time. Their work echoes research done at Columbia University, which also found unique biomarkers of the disease, especially the presence of certain bacteria in the gut.

“Despite diverse data collection methods, common disease signatures emerged in fatty acids, immune markers, and metabolites,” said lead researcher Julia Oh. “That tells us this is not random. This is real biological dysregulation.”

Specifically the team found that ME/CFS patients had lower levels of a fatty acid produced in the gut called butyrate as well as reduced levels of other nutrients that play a role in energy production and overall metabolism. The researchers also found heightened inflammatory responses in T cells (a type of white blood cell) known as MAIT.

“MAIT cells bridge gut health to broader immune functions, and their disruption alongside butyrate and tryptophan pathways, normally anti-inflammatory, suggests a profound imbalance,” said study co-author Derya Unutmaz.

The researchers say their findings can now be explored further to look at developing individualized treatments for ME/CFS patients, much in the same way personalized cancer treatments are emerging as an effective way to combat that disease.

“Our goal is to build a detailed map of how the immune system interacts with gut bacteria and the chemicals they produce,” Oh said. “By connecting these dots we can start to understand what’s driving the disease and pave the way for genuinely precise medicine that has long been out of reach.”

The team also says that its findings could have implications in treating those suffering from long COVID, as it is … [for the balance of this very important article please visit: https://newatlas.com/medical/diagnostic-fatigue-syndrome/]

–

The research has been published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Source: Jackson Laboratory via EurekAlert

–