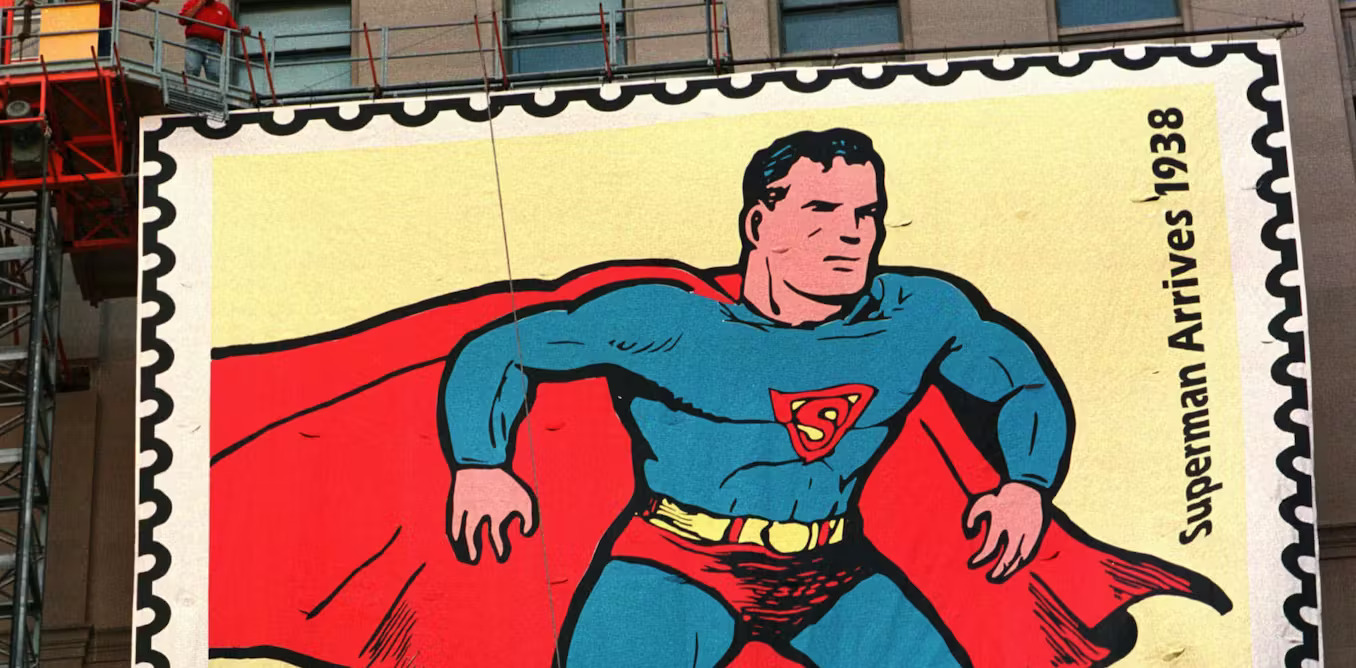

A five-story replica of a stamp of Superman in 1998 in Cleveland, home of the superhero’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. AP Photo/Tony Dejak, File –

A five-story replica of a stamp of Superman in 1998 in Cleveland, home of the superhero’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. AP Photo/Tony Dejak, File –

Published: 2025 Mar 14

–

Nearly a hundred years ago, a hastily crafted spaceship crash-landed in Smallville, Kansas. Inside was an infant – the sole survivor of a planet destroyed by old age. Discovering he possessed superhuman strength and abilities, the boy committed to channeling his power to benefit humankind and champion the oppressed.

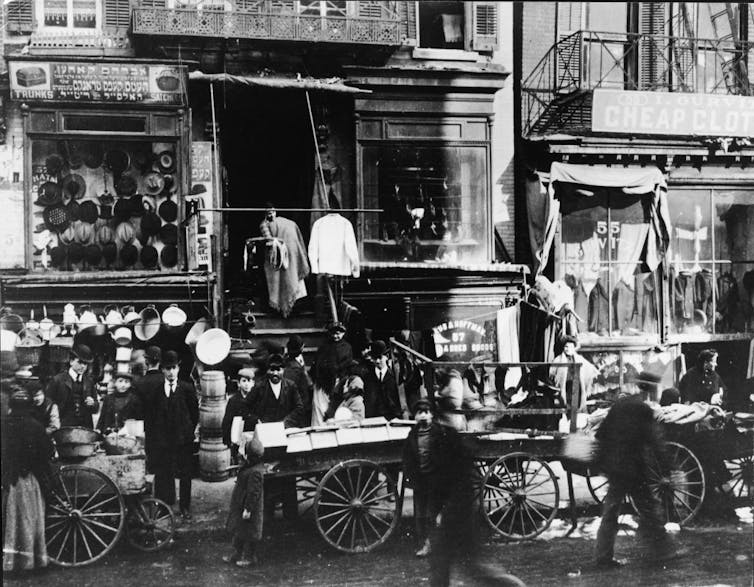

Comic books had not yet been devised, but strip comics in newspapers were a regular feature. They began in the late 19th century with popular stories featuring recurring characters, such as Richard F. Outcault’s “Yellow Kid” and “the Little Bears” by Jimmy Swinnerton.

A few Jewish creators were able to break into the industry, such as Harry Hershfield and his comic “Abie the Agent.” Hershfield’s success was exceptional in three ways: He broke into mainstream newspaper comics, his titular character was also Jewish, and he never adopted an anglicized pen name – as many other Jewish creators felt they must.

–

Generally, however, Jews were barred from the more prestigious jobs in newspaper cartooning. A more accessible alternative was the cheaper, second-tier business of reprinting previously published works.

In 1933, second-generation Jewish New Yorker Max Gaines – born Maxwell Ginzburg – began a new publication, “Funnies on Parade.” “Funnies” pulled together preexisting comic strips, reproducing them in saddle-stitched pamphlets that became the standard for the American comics industry. He went on to found All-American Comics and Educational Comics.

Another publisher, Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, founded National Allied Publications in 1934 and published the first comic book to feature entirely new material, rather than reprints of newspaper strips. He joined forces with two Jewish immigrants, Harry Donenfeld and Jack Leibowitz. At National, they created and distributed Detective and Action Comics – the precursors to DC, which would become one of the two largest comics distributors in history.

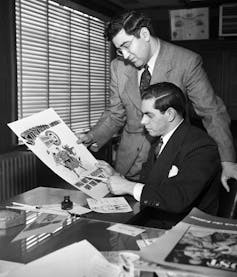

It was at Action Comics that Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two second-generation immigrants from a Jewish neighborhood in Cleveland, found a home for Superman. It would also be where two Jewish kids from the Bronx, Bob Kane and Bill Finger – born Robert Kahn and Milton Finger – found a home for their character, Batman, in 1939.

–

The success of these characters inspired another prominent second-generation Jewish New Yorker, pulp magazine publisher Moses “Martin” Goodman, to enter comics production with his line, “Timely Comics.” The 1939 debut featured what would become two of the early industry’s most well-known superheroes: the Sub-Mariner and the Human Torch. These characters would be mainstays of Goodman’s company, even when it became better known as Marvel Comics.

Thus were born the “big two,” Marvel and DC, from humble Jewish origins.

…and Jewish stories

The creation and popularization of superhero comics isn’t Jewish just because of its history. The content was, too, reflecting the values and priorities of Jewish America at the time: a community influenced by its origins and traditions, as well as the American mainstream.

Some of the most foundational early comics echo Jewish history and texts, such as Superman’s story, which parallels the Jewish hero Moses. The biblical prophet was born in Egypt, where the Israelites were enslaved, and soon after Pharaoh ordered the murder of all their newborn sons. Similarly, Superman’s people, the Kryptonians, faced an existential threat: the destruction of their planet.

Moses’ life is saved when his mother floats him down the Nile in a hastily constructed and tarred basket. Kal-El, too, is sent away to safety in a hastily constructed craft. Both boys are raised by strangers in a strange land and destined to become heroes to their people.

Comics also reflected the feelings and fears of Jews in a moment in time. For example, in the wake of Kristallnacht – the 1938 night of widespread organized attacks on German Jews and their property, which many historians see as a turning point toward the Holocaust – Finger and Kane debuted Batman’s Gotham City. The city is a dark contrast to Superman’s shining metropolis, a place where villains lurked around every corner and reflected the darkest sides of modern humanity.

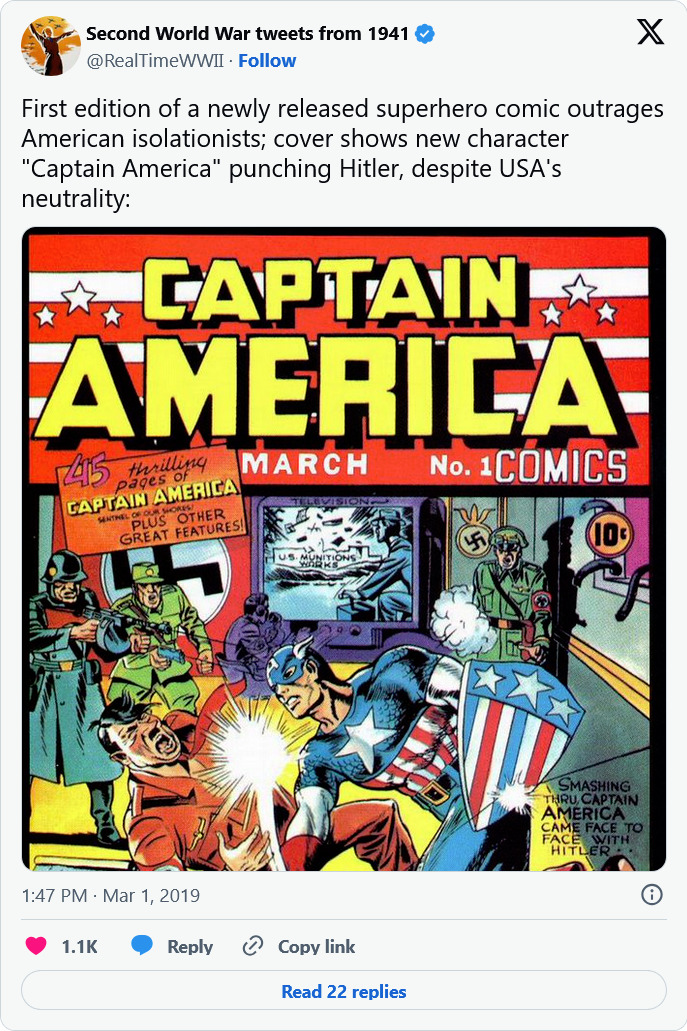

Some comic artists and writers used their platform to make political statements. Jack Kirby – born Kurtzberg – and Hymie “Joe” Simon, creators of Captain America, explained that they “knew what was going on over in Europe. World events gave us the perfect comic-book villain, Adolf Hitler, with his ranting, goose-stepping and ridiculous moustache. So we decided to create the perfect hero who would be his foil.” The comic debut of Captain America in 1941 featured a brightly colored cover with the brand-new hero punching Adolf Hitler in the face.

In later generations, characters penned by Jewish authors continued to grapple with issues of outsider status, hiding aspects of their identity, and maintaining their determination to better the world in spite of rejection from it. Think of Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four and X-Men. All of these were created by Stan Lee – another Jewish creator, born Stanley Martin Lieber – who was hired into Timely Comics at just 17 years old.

With so many of the most popular comics written by New York Jews, and centered in the city, much of New York’s Yiddish-tinged, recognizably Jewish language made its way onto the pages. Lee’s Spider-Man, for example, frequently exclaims “oy!” or calls bad guys “putz” or “shmuck.”

In later years, Jewish authors such as Chris Claremont and Brian Michael Bendis introduced or took over mainstream characters who were overtly Jewish – reflecting an emerging comfort with a more public Jewish ethnic identity in America. In X-Men, for example, Kitty Pryde recounts her encounters with contemporary antisemitism. Magneto, who is at times friend but often foe of the X-Men, developed a backstory as a Holocaust survivor.

History is never solely about retelling; it’s about gaining a better understanding of complex narratives. Trends in comics history, particularly in the superhero genre, offer insight into the ways that Jewish American anxieties, ambitions, patriotism and sense of place in the U.S. continually changed over the 20th century. To me, this understanding makes the retelling of these classic stories even more meaningful and entertaining.

–

–

Partners

University of Michigan provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

–

Trustworthy journalism is needed now more than ever

Here at The Conversation, we work with scholars to bring you the depth of knowledge they have of their field, which rarely makes it into daily news reporting. We provide context and background – and look ahead – beyond the headlines.

We don’t give you opinions – there’s more than enough of that in the world. We don’t tell you what to think. We bring you the facts, the data, the historical context and the analysis so that you can make informed decisions about the very complex reality of life in the 21st century. We don’t publish stories filled with anonymous sources who say things you can’t verify.

Every assertion of fact in our stories has a verifiable source. This is news you can trust.

We’ve got swag we can give you at various levels of support. But I like to think you’d be helping us out for a much nobler reason: You are supporting democracy by supporting our work. That’s why I do what I do. It’s why I hope you’ll pitch in, too.

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 200,000 academics and researchers from 5,149 institutions.