The new drug-delivery system only activates when inside a tumor and calls upon the body’s own immune system to destroy it. ChatGPT –

The new drug-delivery system only activates when inside a tumor and calls upon the body’s own immune system to destroy it. ChatGPT –

Enlisting our innate immune systems to help us combat cancer is one of the most promising, modern ways to deal with the disease. In fact, just this summer, researchers announced the proof of concept of a kind of universal cancer vaccine that works by training our immune systems to blast away any type of cancer cell in the body.

One of the immunological pathways researchers are investigating to combat tumors is called STING, which stands for “stimulator of interferon genes.” The STING pathway acts like a kind of an alarm system in the body. It is activated when a cell signals the presence of stray DNA in its cytoplasm and releases a sensor protein called cGAS. This marshals a STING protein to sit on the membrane of a cell and set off a chain reaction that calls in backup from the rest of the immune system.

To combat cancer, researchers have experimented with drugs called STING agonists that kick off this alarm system to attack tumors, but the issue is that these drugs don’t necessarily work directly at the tumor site. As a result, they can cause excessive inflammation at other spots in the body, which can be dangerous and cause significant side effects.

Seeking to make a better STING agonist, researchers at the University of Cambridge came up with an elegant solution.

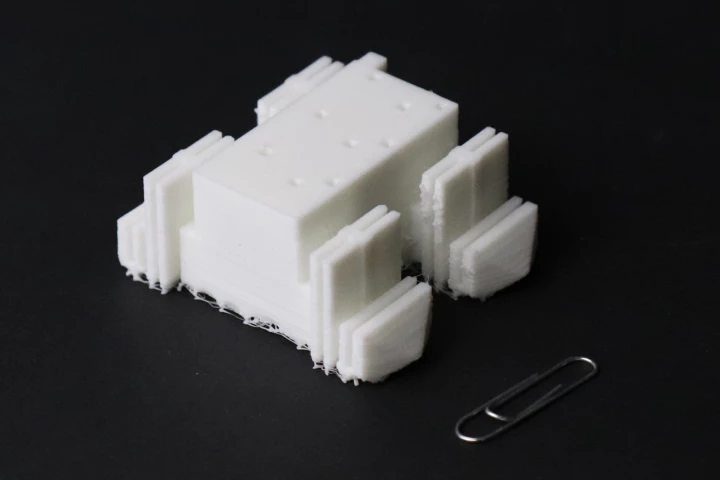

They designed a two-part drug-delivery system in which one part of the drug is chemically “caged” so that it doesn’t activate until it encounters certain conditions. In this case, the caged drug, which is a STING agonist known as MSA2, is released when it encounters an enzyme called β-glucuronidase, which is produced by tumors and not typically found in healthy tissue. When this enzyme uncages the drug, it mixes with the second component inside the tumor and activates the STING pathway, which calls immune system resources to the site to fight and kill the tumor.

“This is like sending two safe packages into the body that only unlock and combine when they meet the tumor’s unique chemistry,” said lead researcher Gonçalo Bernardes. “The result is a strong immune-activating drug that appears only where it is needed.”

The researchers tested their two-part drug on mice and zebrafish engineered to produce β-glucuronidase, and found that the drug was activated almost exclusively in tumors, sparing healthy tissue and organs.

In addition to fighting cancer, the researchers say their breakthrough could help with highly targeted drug delivery across a range of applications.

“This discovery is exciting not only for cancer treatment, but also as a …[for the balance of this exciting article please visit: https://newatlas.com/cancer/caged-drugs-cancer/]

–

The findings have been published in the journal Nature Chemistry.

Source: University of Cambridge via EurekAlert

–