A mad cow-like infectious disease that can turn the brains of deer, elk, and moose into “Swiss cheese.”

A mad cow-like infectious disease that can turn the brains of deer, elk, and moose into “Swiss cheese” is spreading in at least 24 states — and some experts are warning that it could eventually make its way into humans.

Known as chronic wasting disease, the fatal progressive neurodegenerative illness was first identified in the 1960s. Like mad cow, the disease is spread by prions, the zombie-like pathogenic proteins that aren’t alive and can’t be killed. When they infect an animal, they eat away at its brain, causing a cascade of symptoms that resemble dementia and eventually lead to death. While the disease is still rare, researchers believe it’s more widespread than ever due, in part, to how humans trade deer and other hoofed mammals.

“What we’ve seen over the last few decades is that it’s slowly spreading in wild deer populations,” said Peter Larsen, an assistant professor in veterinary sciences at the University of Minnesota who has been studying the pathogen. It’s also spreading among captive deer, elk, and reindeer, which are transported around the country and overseas to hunting ranches, petting zoos, and Christmas-themed farms. That’s how the disease ended up in South Korea, Larsen said. (It’s been identified in Canada and Norway, too.)

When new outbreaks start, they are virtually impossible to contain because, unlike viruses and bacteria, prions can’t be killed. There’s also no good way to find them. So we’re talking about an indestructible, killer pathogen that could be lurking anywhere.

Researchers have long wondered whether the disease, like mad cow, can make the leap into humans. (Mad cow in people is known as Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.) Late last summer, we got a preliminary and frightening answer. In a paper published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, researchers from Scotland and Canada showed via an experiment in a petri dish that prions from sick animals can indeed infect human cells.

Since then, there’s been no direct evidence of human disease, even in people who ate meat that later tested positive for the pathogenic prions. Still, the experimental research spurred Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, to compare chronic wasting disease to mad cow recently.

Osterholm, it turns out, also warned the British government of the risks of mad cow before hundreds of people were infected in the UK and around the world in the late 1990s. Sitting before a state committee in Minnesota on February 7, he called the chances of humans becoming infected with chronic wasting disease “probable” and “possible,” adding: “The number of human cases will be substantial and not isolated events.”

“We don’t want to find out 10 years from now,” Osterholm told Vox, “that we should have been doing something in 2019 but didn’t.”

According to Larsen, it’s not time to freak out, but he warned that this is a growing public health threat. People should not consume infected meat, he said, while also noting there’s actually no good way to know if meat is infected. “There is currently no way for people to rapidly test for prions in meat, on meat processing surfaces, or in live deer,” he said.

Let’s walk through what we know about this emerging infectious disease.

1) What is “zombie deer disease”?

Scientists don’t know where the name “zombie deer disease” emerged. Instead, they refer to chronic wasting disease, a fatal progressive neurodegenerative illness believed to affect deer, elk, reindeer, and moose. It was discovered in farmed deer in Colorado in the 1960s, and it’s been intriguing scientists ever since.

The disease is caused by prions, which are not viruses or bacteria. Prions are almost indestructible pathogenic proteins that trigger cells, particularly in the brain and spinal cord, to fold abnormally and start clumping. When that happens, the infected animals begin to develop an array of awful symptoms — dementia, hallucinations, and difficulty walking and eating. The animals eventually become wobbly and disoriented. Those symptoms worsen over time, and since there’s no cure, they always lead to death.

[This] is a neurodegenerative disease — not a Hollywood zombie disease

The disease got its name because when prions overtake an animal, it begins losing weight and wasting away. The prions “turn the brain into Swiss cheese,” Larsen said.

But Larsen called “zombie deer disease” an unfortunate and potentially misleading moniker. “I have only seen one deer that has died of [chronic wasting disease] and it was emaciated,” he said. “There are no zombie-like symptoms. Instead, the symptoms are what you would expect to see of a very sick animal: thin, weak, and unable to function normally.

“It is important to remember that [this] is a neurodegenerative disease — not a Hollywood zombie disease.”

2) How does it spread in animals?

An animal with chronic wasting disease can spread prions to other animals through direct or indirect contact with bodily fluids such as feces, saliva, blood, or urine. That means that the disease can spread if an infected deer is wounded, for example, and its blood touches an uninfected animal; or if a healthy animal comes into contact with soil, food, or water that’s been contaminated by a sick deer.

That’s not all, Larsen said. Because prions are so robust, they can survive in environments — farms, forests — for years, decades even. “So let’s say you have a deer with chronic wasting disease, and it started shedding [prions] in its urine, feces, saliva.” If that deer dies on the forest floor, the prions can survive and bind to soil, where plants soak them up. Those plants can then spread prions through their leaves, Larsen said.

“So it’s spreading in the wild, slowly. And every year, we see more and more cases of chronic wasting disease.”

3) How would it spread to people?

There have been no documented cases of chronic wasting disease in people, but researchers think it’s possible and becoming more likely, as infections become more prevalent in animals.

So far, the only evidence scientists have of spread beyond hoofed mammals, like deer, is indirect. In lab experiments, scientists have shown that the disease can spread in squirrel monkeys and mice that carry human genes, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says. In a yet-to-be-published study, macaques — a primate species that’s genetically similar to humans — that were fed infected meat contracted the disease.

“Experiments are [also] being performed where researchers take environmental samples, like rocks or pieces of wood, that have [pathogenic] prions on them,” said Larsen. “They then place these contaminated objects in cages with transgenic hamsters and the hamsters develop the disease.”

In a recently published study, researchers found that chronic wasting disease prions infected human cells in a petri dish. But there’s another study tracking people who ate venison that had been exposed to chronic wasting disease in 2005, and so far, they’ve shown no symptoms. It’s possible they were exposed to a less virulent strain of the disease, or that the prions didn’t manage to infect human cells, or that the disease is still incubating in them, Larsen said. “The jury is still out on the dangers of human consumption.”

Even so, the CDC says the experimental studies “raise the concern that [chronic wasting disease] may pose a risk to people and suggest that it is important to prevent human exposures to [the disease].” The most likely way this could happen is if a person, such as a hunter, eats contaminated meat.

That brings us to another troubling fact about chronic wasting disease: “With a prion, you can’t [cook it off]. The temperatures needed to destroy it are far beyond what you can cook with,” Larsen said.

The only way to make prions noninfectious is by using lye, a strong alkaline solution that drastically changes the pH balance, and autoclaving — or pressure-treating them — at 270 degrees Fahrenheit. “Most people don’t have access to this approach,” Larsen said, and “the point is that it’s difficult to manage [infectious] prions in the environment because we don’t know exactly where they lurk.” That brings us to the next problem with this disease.

4) Where is zombie deer disease in the US?

Well, we only know where chronic wasting disease was. Deer can only be diagnosed after they’ve died (researchers need to access tissues that are deep in the animal’s brain, and to test those). But animals can carry the pathogens for years and not show any signs or symptoms. “That deer could go on a 40-mile trip, sprinkling [infected] prions in its feces or urine,” said Larsen. “If we go and say this is a [chronic wasting] deer on this point on the map, what you don’t see on that map is everywhere that deer has been in the last two years.”

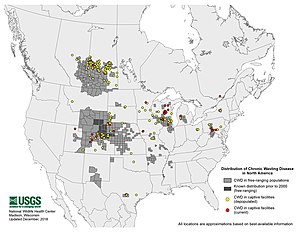

As of January 2019, 251 counties in 24 states had reported chronic wasting disease in free-ranging deer, the CDC reported. You can see them here:

Again, though, researchers think the range of spread is much broader. The CDC has also noted that some states have better animal disease surveillance systems than others, so the current map may be more a reflection of where detection is strongest (and of past disease) than where the deadly prions are currently spreading in the US.

5) Can we stop the disease from spreading?

Since there’s no way to eradicate and cure the disease right now, researchers are recommending that states where it’s known to be spreading try to contain it by identifying sick animals.

Now, here’s another problem: The tools available to do that right now are very limited. The diagnostics for detecting the disease in animals are not always accurate, not all states have access to them, and, again, they can only confirm the presence of the infection in an animal after it’s already dead. It can also take days or weeks to get results. That means the disease may be on the move — or in meat people are eating — for a while before anyone knows it’s there.

“The real test we need is for deer that’s killed, so people know whether the meat [they’re] eating is infected,” Osterholm said.

Along with Osterholm, Jeremy Schefers, a veterinary diagnostician at the University of Minnesota, was recently entreating lawmakers in his state for research funding to develop better diagnostic tools and help scientists answer basic questions about chronic wasting disease. Here’s Schefers speaking to the Minnesota Post:

We need to find infected animals before their death, but we don’t have a test. … We need to know how other animals move CWD prion[s] around the environment, but we don’t have a test for that.

We need to know if the local butcher shop is contaminated and if it can be effectively cleaned, but we don’t have a test for that. We need to know if prions move from the soil into plants and potentially are infective, but we don’t have a test for that. … I want to know how much is in the soil and I want to know how much of it takes to infect something, but we don’t have a test for that.

All hunters need access to a test that can be easily purchased and quickly detect CWD in their deer before it’s cut up into 100 pieces and fed to their family. Those hunters don’t have access to a test.

6) How can people protect animals and themselves?

Health officials are most concerned about the potential for hunters to be to exposed to the disease through animals carrying prions. So anyone who finds themselves hunting in areas where chronic wasting disease is known to spread should take the following precautions, according to the CDC:

- No shooting, handling, or eating elk or deer that look unhealthy or “are acting strangely.”

- When field-dressing (or removing the organs of) a hunted animal, wear latex or rubber gloves, avoid touching the animal’s organs — especially the brain and spinal cord tissues — and avoid using utensils that are also used at home.

- Get deer or elk meat tested for prion disease before eating the meat. Yet the CDC also warns that since the diagnostic tools for the disease are still limited, “A negative test result does not guarantee that an individual animal is not infected” with chronic wasting disease, though it “may reduce your risk of exposure.”

- When getting the meat commercially processed, ask the butcher if they handle and process multiple animals at one time (to avoid cross-contamination).

So what about consumers of game meat, like venison, and the restaurants that serve it? On that, Larsen didn’t have a comforting answer.

He advised that anyone who eats game meat, or a restaurant that serves game, ask about where the meat came from. And restaurants should be making sure their meat is free of the disease. Again, in practice, that’s not easy because of how long it takes to get results from diagnostic tests.

“If you’re a hunter, and shoot a deer to feed your family or sell, are you going to wait two weeks [for a test result]?” Larsen asked. “How do you keep the meat fresh?”

But while consumers might have the right to know whether their meat has been infected with the pathogenic prions, there’s currently no efficient way to get an answer.

“Humans have interacted with deer for centuries,” Larsen said, “for food, sport, or simply watching them in the wild.” That tradition is “under attack now because of this pathogen.”

(For the source of this, and many other important articles, please visit: https://www.vox.com/2019/2/21/18233227/zombie-deer-disease-map/)