If the Sahara were a country, it’d be the fifth largest in the world.

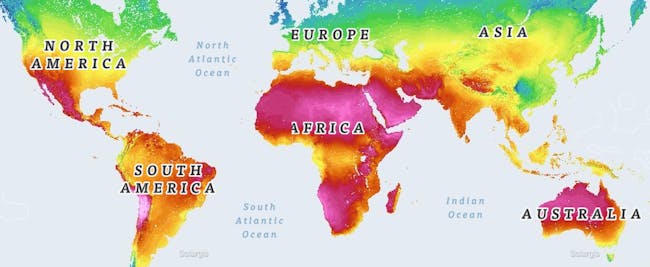

Whenever I visit the Sahara I am struck by how sunny and hot it is, and how clear the sky can be. Aside from a few oases, there is little vegetation, and most of the world’s largest desert is covered with rocks, sand, and sand dunes. The Saharan sun is powerful enough to provide Earth with significant solar energy.

The statistics are mind-boggling. If the desert were a country, it would be the fifth biggest in the world — it’s larger than Brazil and slightly smaller than China and the US. Each square meter receives, on average, between 2,000 and 3,000 kilowatt hours of solar energy per year, according to NASA estimates. Given the Sahara covers about 9m km², that means the total energy available — that is, if every inch of the desert soaked up every drop of the sun’s energy — is more than 22 billion gigawatt hours (GWh) a year.

See also: Floating Solar Panels: World’s Largest Installation to Set Sail This Year

This is again a big number that requires some context. It means that a hypothetical solar farm that covered the entire desert would produce 2,000 times more energy than even the largest power stations in the world, which generate barely 100,000 GWh a year. In fact, its output would be equivalent to more than 36 billion barrels of oil per day — that’s around five barrels per person per day. In this scenario, the Sahara could potentially produce more than 7,000 times the electricity requirements of Europe, with almost no carbon emissions.

What’s more, the Sahara also has the advantage of being very close to Europe. The shortest distance between North Africa and Europe is just 15km at the Strait of Gibraltar. But even much further distances, across the main width of the Mediterranean, are perfectly practical — after all, the world’s longest underwater power cable runs for nearly 600km between Norway and the Netherlands.

Over the past decade or so, scientists (including me and my colleagues) have looked at how desert solar could meet increasing local energy demand and eventually power Europe, too — and how this might work in practice. And these academic insights have been translated in serious plans. The highest-profile attempt was Desertec, a project announced in 2009 that quickly acquired lots of funding from various banks and energy firms before largely collapsing when most investors pulled out five years later, citing high costs. Such projects are held back by a variety of political, commercial, and social factors, including a lack of rapid development in the region.

More recent proposals include the TuNur project in Tunisia, which aims to power more than 2m European homes, or the Noor Complex Solar Power Plant in Morocco, which also aims to export energy to Europe.

Two Technologies

There are two practical technologies at the moment to generate solar electricity within this context: concentrated solar power (CSP) and regular photovoltaic solar panels. Each has its pros and cons.

Concentrated solar power uses lenses or mirrors to focus the sun’s energy in one spot, which becomes incredibly hot. This heat then generates electricity through conventional steam turbines. Some systems use molten salt to store energy, allowing electricity to also be produced at night.

CSP seems to be more suitable to the Sahara due to the direct sun, lack of clouds, and high temperatures, which makes it more efficient. However, the lenses and mirrors could be covered by sand storms while the turbine and steam heating systems remain complex technologies. But the most important drawback of the technology is its use of scarce water resources.

Photovoltaic solar panels instead convert the sun’s energy to electricity directly using semiconductors. It is the most common type of solar power as it can be either connected to the grid or distributed for small-scale use on individual buildings. Also, it provides reasonable output in cloudy weather.

But one of the drawbacks is that when the panels get too hot, their efficiency drops. This isn’t ideal in a part of the world where summer temperatures can easily exceed 45 degrees Celsius in the shade, and given that demand for energy for air conditioning is strongest during the hottest parts of the day. Another problem is that sand storms could cover the panels, further reducing their efficiency.

Both technologies might need some amount of water to clean the mirrors and panels depending on the weather, which also makes water an important factor to consider. Most researchers suggest integrating the two main technologies to develop a hybrid system.

Just a small portion of the Sahara could produce as much energy as the entire continent of Africa does at present. As solar technology improves, things will only get cheaper and more efficient. The Sahara may be inhospitable for most plants and animals, but it could bring sustainable energy to life across North Africa — and beyond.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Amin Al-Habaibeh. Read the original article here.