By BBC –

Ruja Ignatova called herself the Cryptoqueen. She told people she had invented a cryptocurrency to rival Bitcoin, and persuaded them to invest billions. Then, two years ago, she disappeared. Jamie Bartlett spent months investigating how she did it for the Missing Cryptoqueen podcast, and trying to figure out where she’s hiding.

In early June 2016 a 36-year-old businesswoman called Dr Ruja Ignatova walked on stage at Wembley Arena in front of thousands of adoring fans. She was dressed, as usual, in an expensive ballgown, wearing long diamond earrings and bright red lipstick.

She told the cheering crowd that OneCoin was on course to become the world’s biggest cryptocurrency “for everyone to make payments everywhere”.

Bitcoin was the first cryptocurrency and is still the biggest and best-known – its rise in value from a few cents to hundreds of dollars per coin by mid-2016 had given rise to a frenzy of excitement among investors. Cryptocurrency as an idea was just entering the mainstream. Lots of people were looking to get involved in this strange new opportunity.

OneCoin, Dr Ruja told the Wembley audience, was the “Bitcoin Killer”. “In two years, nobody will speak about Bitcoin any more!” she shouted.

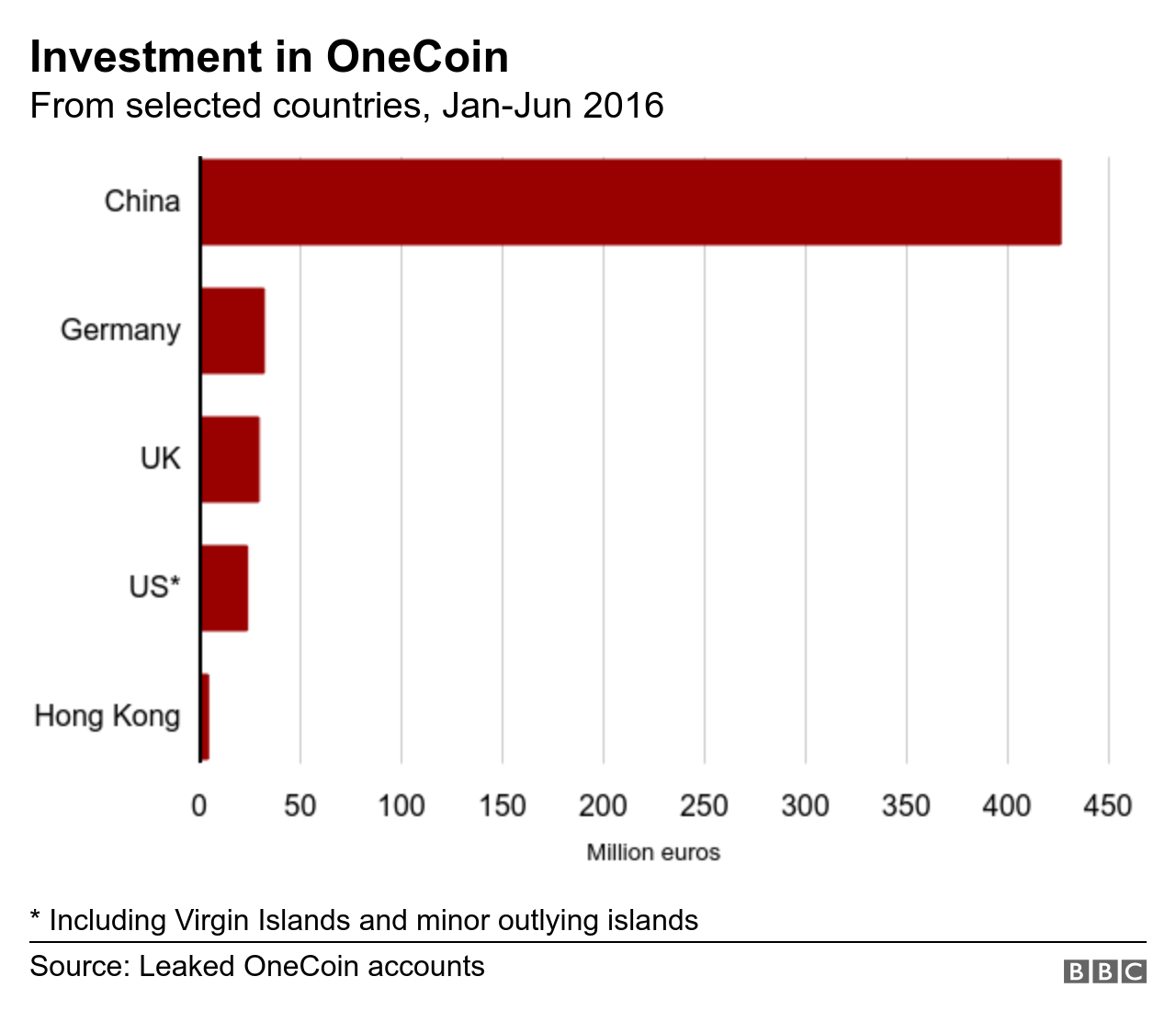

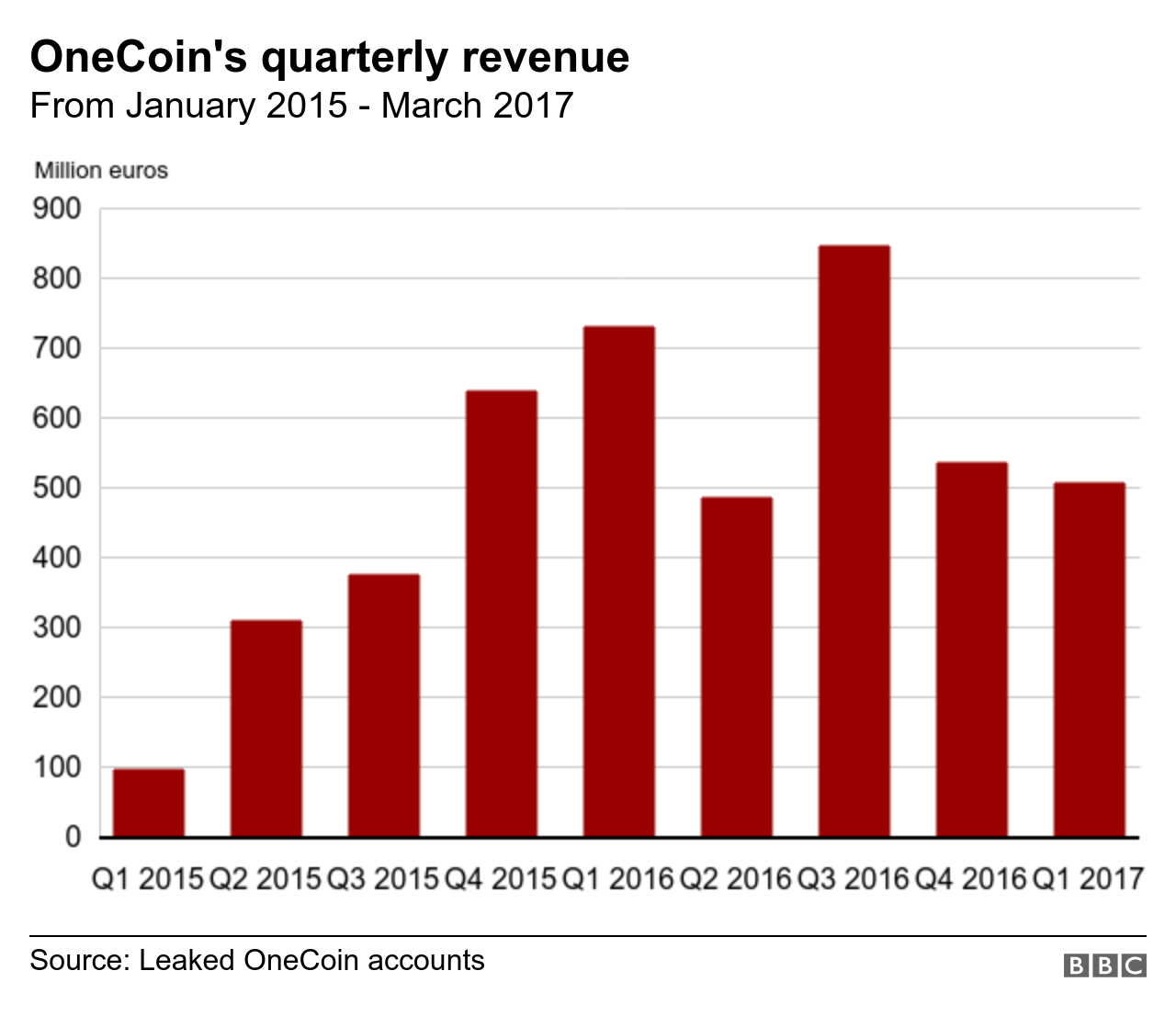

All over the world, people were already investing their savings into OneCoin, hoping to be part of this new revolution. Documents leaked to the BBC show that British people spent almost €30m on OneCoin in the first six months of 2016, €2m of it in a single week – and the rate of investment could have increased after the Wembley extravaganza. Between August 2014 and March 2017 more than €4bn was invested in dozens of countries. From Pakistan to Brazil, from Hong Kong to Norway, from Canada to Yemen… even Palestine.

But there was something very important these investors didn’t know.

To explain this, I need first to explain briefly how a cryptocurrency actually works. This is notoriously difficult – go online and you’ll find hundreds of different descriptions, some of them utterly baffling to the non-specialist. But this is the first principle to grasp: money is only valuable because other people think it’s valuable. Whether it’s Bank of England notes and coins, shells, precious stones or matchsticks – all of which have historically been used as money – it only works when everyone trusts it.

For a long time, people have tried to create a form of digital money independent of state-backed currencies. But they have always failed because no-one could trust them. They would always need someone in charge who could manipulate the supply, and forgery was too easy.

Image copyright Shutterstock

Image copyright Shutterstock

The reason so many people are excited by Bitcoin is that it solves that problem. It depends upon a special type of database called a blockchain, which is like a huge book – one that Bitcoin owners have independent but identical copies of. Every time a Bitcoin is sent from me to someone else, a record of that transaction goes into everyone’s book. Nobody – not banks, not governments, or the person who invents it – is in charge or can change. There is some very clever math behind all this, but this means that Bitcoins can’t be faked, they can’t be hacked and can’t be double-spent.

(I tested this explanation on my mother, the family technophobe, and she told me I’d failed to make it clear enough and should start again. So don’t worry too much if you don’t follow it either.) The key point is that these special blockchain databases are what make cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin work. For its fans this is a revolutionary new form of currency, with the potential to sideline the banks and national currencies, and provide banking for anyone with a mobile phone. And if you get in early, there’s the chance to make a fortune.

Dr Ruja’s genius was to take all of this and sell the idea to the masses.

But there was something wrong. In early October 2016 – four months after Dr Ruja’s London appearance – a blockchain expert called Bjorn Bjercke was called by a recruitment agent, with a curious job offer. A cryptocurrency start-up from Bulgaria was looking for a chief technical officer. Bjercke would get an apartment and a car – and an attractive annual salary of about £250,000.

“I was thinking: ‘What is my job going to be? What are the things that I’m going to have to do for this company?'” he recalls.

“And he said: ‘Well, first of all, they need a blockchain. They don’t have a blockchain today.’

“I said: ‘What? You told me it was a cryptocurrency company.'”

The agent replied that this was correct. It was a cryptocurrency company, and it had been running for a while – but it didn’t have a blockchain. “So we need you to build a blockchain,” he went on.

“What’s the name of the company?” asked Bjercke.

“It’s OneCoin.”

He didn’t take the job.

NOTE: For the balance of this rather lengthy article please visit: https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-50435014