Each day, 80% of the workforce showed up to work while 20% stayed home. Workers received a color code corresponding to their day off. Husbands and wives often worked opposite schedules, meaning families lost their shared day of rest. The move was incredibly unpopular, with one letter in Pravda complaining, “What is there for us to do at home if our wives are in the factory, our children at school, and nobody can visit us?”

The five-day week wasn’t the first change to the Russian calendar, but it had the greatest impact. The new Soviet Union calendar tore families apart and wiped out religious communities. Yet one group ignored Stalin and continued to follow a Soviet Union calendar with weekends – while still taking off the new state-sponsored revolutionary holidays.

Maximizing productivity was a top agenda item in the USSR, and in 1929, Yuri Larin came up with a revolutionary plan. Instead of closing the factories on Sundays, why not switch to a continuous work week? With machines running every day, the Soviets could surely meet the production goals of Stalin’s five-year plan.

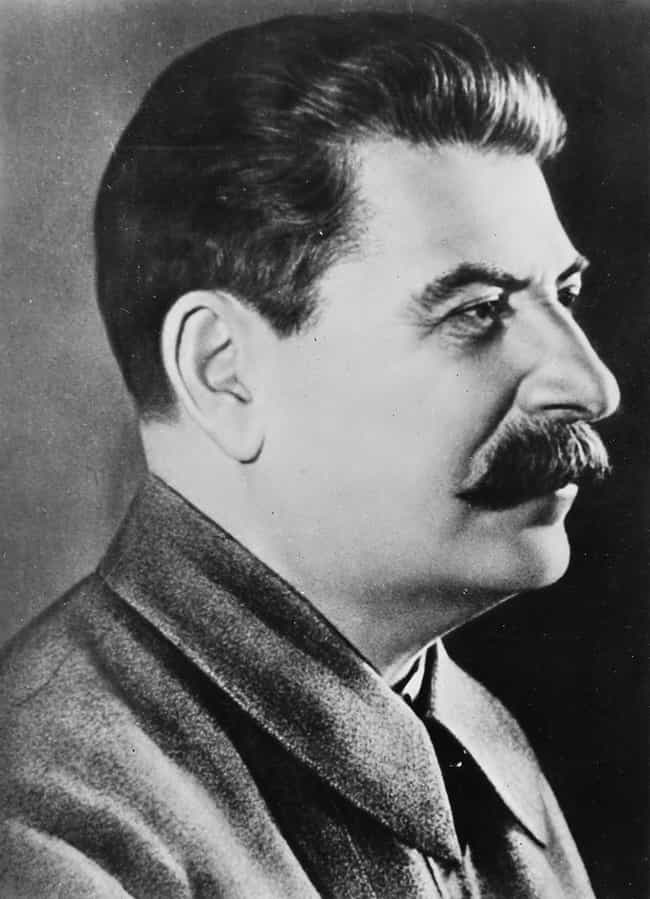

Josef Stalin loved the idea. By August of 1929, the Council of People’s Commissars ordered a five-day work week, completely eliminating Saturdays and Sundays. The new calendar went into effect just weeks later.

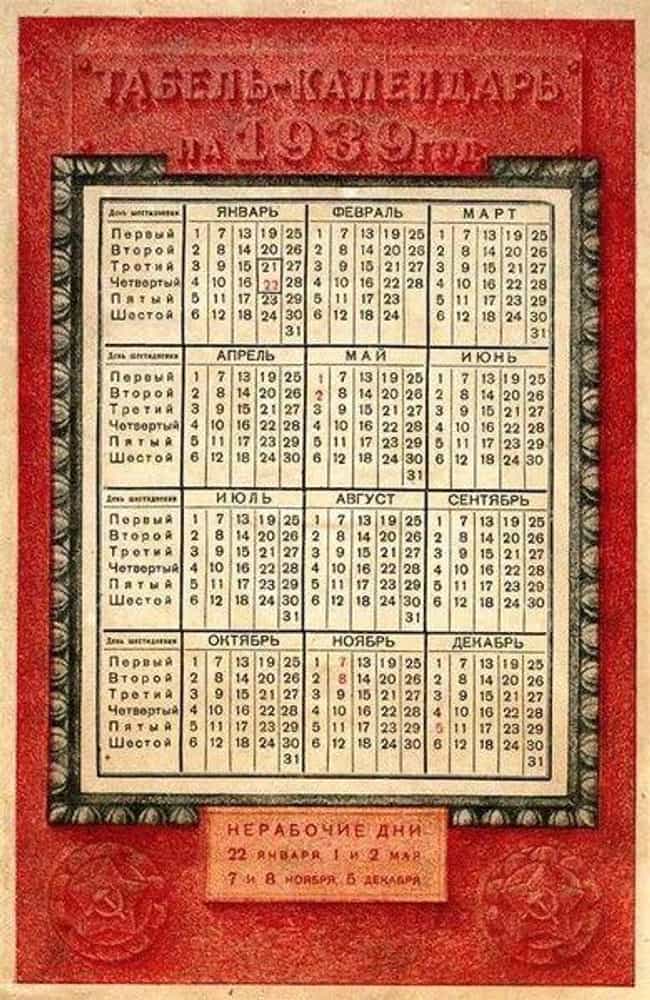

Known as the nepreryvka, or “uninterrupted” work week, the new calendar changed life radically in the Soviet Union. Under the new Soviet Eternal Calendar, the USSR divided the year into five-day weeks, with six weeks in each month. The government added five holidays throughout the year to equal 365 days.

Every Soviet worker clocked in for a four-day shift each week, with one rotating day off. But the plan never considered how the staggered rest days would change life for Soviet workers.

To help workers adjust to the new system, the USSR introduced a color-coded system. Each day came with a color: yellow, peach, red, purple, or green. All the green workers took that day off, while the red workers took off red days.

The Soviet Eternal Calendar also carried new symbols for days of the week, since the Soviets no longer recognized old names like Monday or Tuesday. Instead, a red star and a military cap symbolized different days of the week.

When the Soviet Eternal Calendar went into effect, husbands and wives were often given opposite schedules. While one spouse might have first day off, the other might take fifth day off. Under the system, spouses rarely shared any days off in the year.

After several months operating on the Soviet Eternal Calendar, the government finally considered granting simultaneous breaks for spouses. Families could petition the government for the same day off, but there was no guarantee of approval.

Soviets complained about the five-day calendar from the beginning. Pravda, the official newspaper of the Soviet Communist Party, published a letter from an anonymous worker who criticized the system.

In the letter, the worker complained:

What are we to do at home if the wife is in the factory, the children in school, and no one can come to see us? What is left but to go to the public tea room? What kind of life is that – when holidays come in shifts and not for all workers together? That’s no holiday, if you have to celebrate by yourself.

With husbands, wives, and children on opposite schedules, Soviet families were torn apart. One worker complained, “How are we to work now, if mother is free on one day, father on another, brother on a third, and I myself on a fourth?”

But some considered the cost to families a benefit of the calendar. Just before the new calendar went into effect, Ivan Ivanovich Shitz wrote in his diary that the continuous working week would make it impossible for people to meet as a family or join religious or political groups. He believed that eliminating these associations would bond people more closely with the state.

The USSR tried to give the new calendar days revolutionary names. One would be called “Trade Union,” another was “Hammer,” and a third “Sickle.” They even considered names like “Lenin” and “Soviet.”

But the revolutionary names never caught on. Instead, Soviets simply began to refer to the days by their number or color.

The colors associated with the five-day calendar became shorthand for the days of the week. Some even marked colors in their address books as a shorthand code for which day of the week a friend had off work.

Not surprisingly, Soviets soon socialized by color. A worker who only had the green day off couldn’t easily maintain a friendship with someone who had the purple day off. In an entire year, two workers on different schedules would only share five days off in common.

The five-day week didn’t last long in the Soviet Union. After protests from workers, the government finally decided to introduce yet another new calendar.

The 1931 calendar added back Saturdays, shifting to a six-day week. Under the new system, all workers took a rest day together on Saturdays, which always fell on the 6th, 12th, 18th, 24th, and 30th of the month.

The six-day work week lasted for nearly another decade in the USSR.

Stalin believed the new five-day calendar would boost productivity. When considering the Soviet Eternal Calendar, the USSR mainly emphasized factories that fell silent on the weekend. But one major sector of the Soviet economy practically ignored the new calendar: farmers.

In rural areas, farmers already worked every day of the week. There were no purple days off on farms, nor were there staggered shifts. Historian Malte Rolf reports that in 1931, “almost all officials were complaining about the still existing ties of rural people to ‘traditional habits.'”

However, farmers did adopt part of the Soviet Eternal Calendar. They took off the new state holidays, in addition to taking off traditional religious holidays.

The Soviet efforts to manipulate the calendar and the working day didn’t start in 1929. In 1928, the USSR announced a reduction of the working hours. Instead of an eight-hour day, workers would spend just seven hours at work.

The shorter working day was part of Stalin’s five-year plan, and in 1929, the USSR announced that all industries must incorporate shorter working hours and extra time off throughout the year. In exchange, industries had to increase production by using a three-shift system. With factories running night and day, production increased – though at the cost of workers forced to take the night shift.

Soviets Used The New Calendar To Target Religion. Photo: Маяковский/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

The continuous working week wasn’t just about productivity. It was also about breaking the religious associations with the calendar.

Sociologist Eviatar Zerubavel argues that “the main purpose of abolishing the seven-day week in the Soviet Union was to destroy religion there.” Without Saturday or Sunday, Jews and Christians had to completely rearrange their worship times. And with only 20% of the workforce off work on any day of the week, it was difficult to maintain religious congregations.

Photo: Маяков

Stalin’s change to the Soviet calendar wasn’t the first time the USSR tinkered with calendars. Lenin also agreed to change the Soviet calendar in 1917.

However, Lenin’s change brought the USSR in line with the rest of the world. Prior to 1917, Russia used the Julian calendar, which was 12 days behind the more common Gregorian calendar.

Lenin ordered the Soviets to skip 12 days in February 1918 and start the month with February 14 to catch up with the Gregorian calendar. The shift, though less major than eliminating the weekends, did alter history. Under the new calendar, the Soviet October Revolution actually took place in November.

Stalin Brought Back The Seven-Day Week In 1940. Photo: Kalnroze/Wikimed

Stalin finally admitted defeat in 1940. On June 26, 1940, he reinstated the seven-day week. Sundays were once again holidays.

However, in order to meet its strict productivity goals, the USSR passed harsh penalties for tardy or absent workers. Those who missed one day of work, or came to work more than 20 minutes late, were guilty of misconduct and faced mandatory prison. The return of the weekends may have come at too high a cost for some Soviet workers.

(For the source of this article, and other quite interesting articles, please visit: https://www.ranker.com/list/soviet-union-calendar-weekends/genevieve-carlton/)