–

If you’re a woman, especially in a male-dominated field, you probably know what it feels like to be overshadowed by male colleagues, even when you’re doing better work than them. All of the women on this list know what that feels like. The group is comprised of scientists, artists, writers, inventors, and humanitarians, who never got credit for their remarkable achievements, and were snubbed when sexism reared its ugly head.

The most remarkable thing about these women is that most of them continued to do hard work in their fields, despite the lack of recognition. They’re regarded as trailblazers who wouldn’t let the chauvinistic world hold them back.

Let’s celebrate these women for their accomplishments.

–

Zelda Fitzgerald was married to great American novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of The Great Gatsby. Zelda was a writer herself – such a good writer that her husband actually plagiarized her diary.

F. Scott Fitzgerald lifted entire passages from his wife’s diary and put them in his novel, The Beautiful and the Damned. After Zelda read the novel and recognized her own writing, she wrote a review of the novel for the New York Tribune. It said, “Mr. Fitzgerald – I believe that is how he spells his name – seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

While hospitalized, Zelda began work on a semi-autobiographical novel called Save Me the Waltz and sent a draft to Max Perkins, her husband’s editor. Fitzgerald offered to edit the manuscript, but instead he lifted long passages and used them in his own novel, Tender Is the Night.

Many believe Fitzgerald intentionally stoked the rumors that Zelda was “crazy” in order to cover his blatant theft of her literary work. In his journal, Fitzgerald explicitly stated his plans to drive his wife towards a nervous breakdown in order to have her committed.

–

Rosalind Franklin was a scientist whose data was an essential part of figuring out the structure of the DNA molecule. Jim Watson and Francis Crick won the Nobel Prize for discovering that DNA was shaped like a spiral staircase – but Watson and Crick couldn’t have cracked the code without Franklin’s work.

Franklin made two major contributions. First, she helped take a photo of DNA (known as Photo 51) that was clearer than any photo of DNA that had been previously taken at that time. Second, she recorded the distances between the redundant components of the DNA molecule – this where the DNA “repeats.” Without even asking Franklin whether they could use her data, Watson and Crick got their hands on a report she had written containing the numbers they needed to do the final calculation.

As with many women in male-dominated fields, her “masculine” behavior was considered off-putting by many: “Her manner was brusque and at times confrontational – she aroused quite a lot of hostility among the people she talked to, and she seemed quite insensitive to this.”

There is some question about how ethical it was for Watson and Crick to use Franklin’s data. Franklin had not published her measurements for the public to read, but wasn’t exactly keeping them under lock and key, either. In any case, when Watson and Crick achieved their final breakthrough, they were awarded with the Nobel Prize.

Tragically, Franklin died of cancer at age 38 before the prize was awarded (and the Nobel is not awarded posthumously). Watson and Crick went on to become household names, while Franklin’s important contributions were all but forgotten.

–

Margaret Keane’s story was the subject of Tim Burton’s 2014 film, Big Eyes. For years, Keane painted portraits of people with huge eyes, and her husband, Walter, sold them. But Margaret was unaware that Walter was actually taking credit for the paintings himself.

When Margaret realized that her emotionally abusive husband was passing off her work as his own, she was at first convinced to go along with it. But in 1970, Margaret came out and claimed ownership of her paintings. When her husband said she was lying, she sued him for defamation.

Margaret won her lawsuit by producing a painting right before the jurors’ eyes. She was awarded $4 million in damages, but never got the money, because Walter Keane had squandered the entire fortune he made selling her work.

Margaret Steffin

–

Margaret Steffin was one of many women taken advantage of by 20th century playwright Bertolt Brecht. Brecht revolutionized theater with his “alienating” style of drama. His plays laid the foundation for many great theatrical works of the 20th century, including Waiting for Godot by Samuel Becket.

The problem is: Brecht didn’t actually write his own plays. Brecht would seduce women and convince them to write plays for him by promising to marry them.

Margaret Steffin was one of these women whom Brecht swindled. According to Brecht scholar John Fuegi, Steffin wrote at least eight of Brecht’s plays, including Mother Courage and Her Children, The Good Person of Szechwan, Life of Galileo, and early drafts of The Caucasian Chalk Circle. All of the manuscripts are in Steffin’s handwriting, and draw from source material written in French, which Brecht could not read.

To add insult to injury, Brecht wrestled Steffin’s family out of all their inheritance when she died of tuberculosis.

–

Vera Rubin was an astronomer who proved the existence of dark matter. She made this discovery after observing the Andromeda Galaxy in the late 1970s, when she noticed that the things at the edge of the galaxy rotated just as quickly as the things at the center in violation of Newton’s Laws of Motion.

Rubin eventually figured out that the cause of this seemingly nonsensical motion was dark matter, an invisible substance that makes up about 80 percent of the universe. Rubin’s observations of Andromeda served as the first concrete evidence that dark matter actually exists.

Rubin has always retained ownership of her discovery, but was never awarded the Nobel Prize for it. Every year she was passed over, and the award was given to male scientists who had discovered other things widely considered to be of less importance.

–

Jocelyn Bell Burnell was an astronomer who discovered pulsars – stars that emit beams of electromagnetic radiation – before she even finished graduate school.

The discovery of pulsars was critical because it proved that after stars explode into supernovas, they don’t just disappear. Rather, they leave behind dense, rotating stars that send out radiation beams.

About her time as one of the few women studying science, she said,

It was distinctly tough. I ended up in the final two years of my course as the only female in the class, there were 49 men and me. There was a tradition among the students that when a female walked into a lecture theater all the guys stamped and whistled and called and banged the desk. And I faced that for every class I walked into for my last two years.

The Nobel Prize for this discovery went to Burnell’s supervisor, Anthony Hewish, and another radio astronomer at the same university named Martin Ryle, but Burnell was snubbed. She says,

In those days, it was believed that science was done, driven by great men… It also came at the stage where I had a small child and I was struggling with how to find proper childminding, combine a career, and before it was acceptable for women to work. And so I think at one level it said to me, “Well, men win prizes and young women look after babies.”

Ever since she was snubbed, Burnell has been working to protect women in academia.

–

Esther Lederberg was a microbiologist who made several important discoveries in her field in the 1950s. Perhaps her most important contribution to the field of microbiology was developing a lab technique called replica plating, which allows scientists to easily transfer bacteria from one petri dish to another. Replica plating was crucial to researching antibiotics, and scientists today still use it.

Despite developing the replica plating technique with her husband, Joshua, it was Joshua and two other male scientists who won the Nobel Prize in 1958. To top it all off, Lederberg never won the Nobel for her discovery of the lambda bacteriophage, the accomplishment for which she was best known.

–

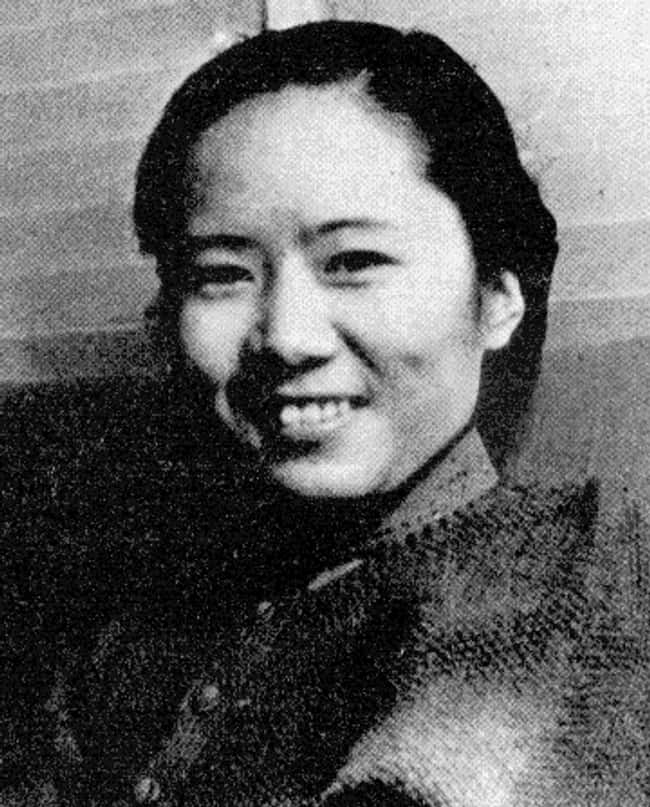

Chien-Shiung Wu was one of the most brilliant physicists of the mid-20th century. But for her most important discovery, she was snubbed by her male colleagues and experienced prejudice both as a woman and an Asian-American immigrant.

Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang asked Wu to help them disprove the law of parity, which says two physical systems – such as atoms – that were mirror images would behave identically. This law had been accepted for 30 years, but Wu disproved it by performing experiments with radioactive cobalt.

In 1957, Yang and Lee won the Nobel Prize, and Wu was left out. Later in life, she became an outspoken advocate for women in science, as well as a critic of human rights violations in her native China. At a symposium at MIT in 1964, she asked,

I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.

Lise Meitner

–

Lise Meitner was a physicist who, despite playing an integral role in the discovery of nuclear fission, never received credit for her work. A young protegy, Meitner was introduced to Einstein and Max Planck; her single-minded focus on physics meant she was never engaged in any romantic relationships but lived for her work.

Meitner worked with another scientist named Otto Hahn. Hahn was tasked with performing the experiments that produced evidence supporting the concept of nuclear fission, while Meitner wrote the theory that explained Hahn’s experimental results. However, Hahn published the paper of their findings without Meitner’s name on it.

Some accounts say Meitner, who was Jewish and hiding in Sweden at the time, consented to her name being left off the paper because it was published in the midst of World War II. While that may be true, Meitner never managed to gain recognition for her role, even after the war had ended. It was Hahn alone who won the Nobel Prize in 1944, while Meitner was left out of the historical account of this discovery that changed the world:

Over the years, this version of the tale lived on. Meitner, Hahn’s equal partner at the Institute for 30 years, came to be mistakenly known as his junior assistant.

Happily, Meitner received a great posthumous honor in 1994 when element 109 was named “meitnerium.”

[Editor’s Note: Meitner received the Enrico Fermi Award in 1966 from the US Department of Energy.]

Nettie Stevens

–

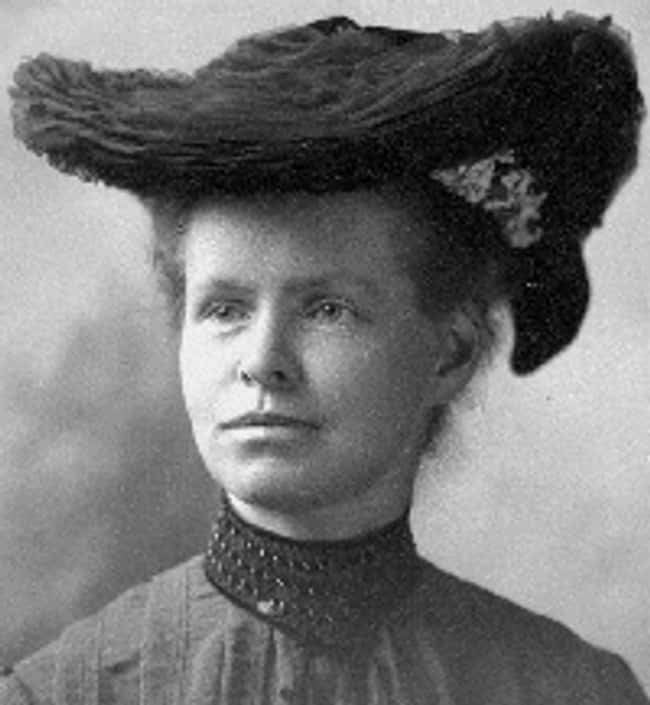

Nettie Stevens was a geneticist who in 1906 made the groundbreaking discovery that an organism’s sex was determined by its chromosomes.

Scientists had previously thought sex was determined by environment, but Stevens found evidence that proved otherwise. She performed experiments with meal worms and found that some sperm carried an X chromosome while other sperm carried a Y chromosome.

However, the credit for discovering genetic sex determination went to Thomas Hunt Morgan, who won the Nobel Prize in 1933. Though Morgan spoke warmly of Stevens following her death from breast cancer at age 50, Stevens’s crucial role went largely unacknowledged by the public.

–

Ada Lovelace (the daughter of the poet Lord Byron) was a mathematician who wrote instructions for how to build a computer – a full century before the first computer was invented.

In the early 1840s, Lovelace’s mentor Charles Babbage asked her to translate an article about a device he was creating called an analytical engine, which you might call a kind of proto-computer. Lovelace went above and beyond her task by adding detailed notes to the article about how the device could be improved. Those notes included how to use code to program a computer, along with many other revolutionary concepts.

Lovelace’s notes were published as their own paper in 1843, but she did not get credit for her work until the 1950s. Had anyone paid attention to the work when it first came out, the first computer may have been invented much earlier.

Florence Deeks

–

Florence Deeks was a Canadian writer and teacher who was [apparently] ripped off by H.G. Wells, the successful English author of The Time Machine. H.G. Wells’s most notable work of non-fiction, The Outline of History, was [very likely] plagiarized from Deeks’s non-fiction book, Web of the World’s Romance.

The most obvious evidence that the book was plagiarized lies in the fact that Walls made many of the same mistakes Deeks made. Both writers spelled Hatshepsut “Hatasu,” an anachronistic spelling that was not at all common during in the 20th century. Both claimed the Phoenicians traded by land, not by sea, and both incorrectly described Roman general Sulla as “aristocratic.” There was also the fact that both world history books left Adam Smith and much of the history of India out altogether.

Deeks sued Wells for copyright infringement, and not only lost the case, but was publicly humiliated by the judge.

Lee Krasner

–

Lee Krasner was the wife of Jackson Pollock, who is considered to be the leader of the Abstract Expressionist art movement. Pollock never tried to take credit for artwork that his wife created, but there’s no doubt that he completely overshadowed her, even though her work was just as revolutionary and brilliant as Pollock’s was.

Krasner met Pollock when the two became founding members of American Abstract Artists in 1936. As Pollock’s fame grew, the task of managing his career fell to Krasner, and her artwork took a backseat. She didn’t begin to shine in her own light until after her husband’s death, when the feminist movement of the ’60s and ’70s highlighted her work. Polluck remains a household name in the world of modern art, while Krasner’s name is hardly ever recognized.

–

Emilie Schindler was the wife of the renowned humanitarian Oskar Schindler. The film Schindler’s List commemorates Oskar’s effort to save the lives of 1,300 Jews during World War II. The film portrayed Emilie as a supportive partner, but in reality, Emilie was just as involved in the life-saving mission as her husband was.

Oskar Schindler was a man who owned a factory that produced war supplies and convinced the Nazis not to take away any of his Jewish employees because they were essential laborers. Schindler also purposely manufactured faulty bullets to covertly sabotage the Nazis. On one occasion Emilie Schindler intercepted a caravan of four wagons transporting 250 Jews to a death camp. She convinced the Nazis to instead let her take the Jews to her husband’s factory and put them to work.

Once Emilie had taken all the prisoners back to the factory, she nursed them back to health. Even when food was scarce and rations were restricted by the government, Emilie managed to find enough food to help the starving victims recover.

Emilie’s heroism was largely left out of the Oscar-winning film about her husband. Several years after the film was released, a journalist named Erika Rosenberg published a biography about Emilie Schindler to highlight her courageous work.

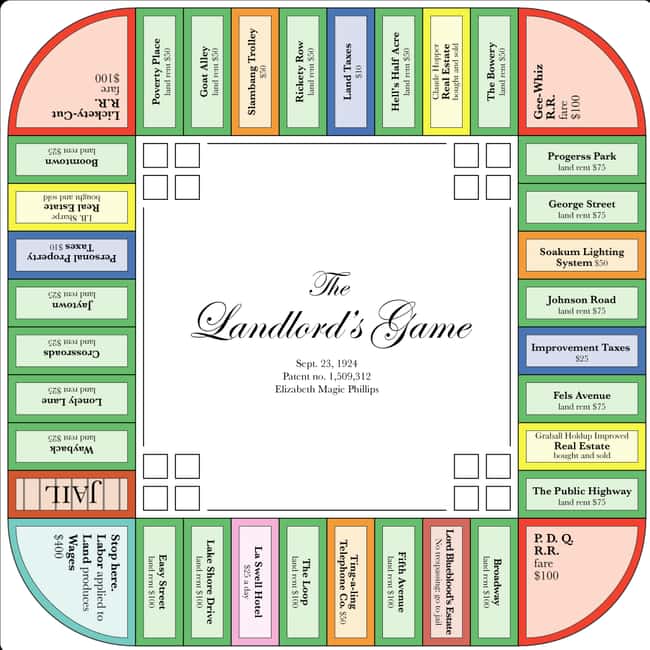

Elizabeth Magie

–

Charles Darrow is typically credited with inventing the board game Monopoly during the Great Depression. But a woman named Elizabeth Magie actually came up with the idea decades before Darrow did.

Magie’s version, The Landlord’s Game, was far more clever (and politically progressive) than Darrow’s version. Magie designed her game to have two sets of rules: The first rewarded all the players when wealth was created, and the second rewarded only the players who created monopolies and squelched their competition. Magie’s goal was to teach people who played the game that the first set of rules was better.

Darrow didn’t agree with Magie’s view. He stole her game, stripped it of the first set of rules, and passed the final version off as his own. Magie had sold her game to Parker Brothers and received a mere $500 for it. Charles Darrow sold his version to Parker Brothers years later, and went on to make millions. Magie died in 1948 without ever getting the credit or the money she was due for her creation.

–

In 1973, when she was still a graduate student, Candace Pert discovered the brain’s opiate receptor. Pert’s discovery enabled scientists to create new psychiatric drugs, and her technique is still widely used by those studying different brain receptors.

However, the credit for Pert’s discovery went to a man named Solomon H. Snyder, the head of the lab where Pert worked. After Snyder received an award for the discovery, and Pert argued that the award should have been hers, Snyder responded, “That’s how the game is played.”

Despite never receiving credit for her groundbreaking discovery, Pert continued to work in the field of neuroscience until she died in 2013.

–

(For the source of this, and many other equally intriguing articles, please visit: https://www.ranker.com/list/women-in-history-who-didnt-get-credit-for-their-work/katherine-ripley/)