A great deal of research over the past few decades has explored the physiological mechanisms underpinning stress responses. We know a great deal about how organisms physically respond to stress and how our brains generate those responses. But less is known about how our brains create a subjective feeling of stress.

Prior study has delivered great insight into how the hippocampus is a key brain region in emotional regulation. This new study from Yale University set out to understand what contribution the hippocampus makes in our subjective sensation of stress.

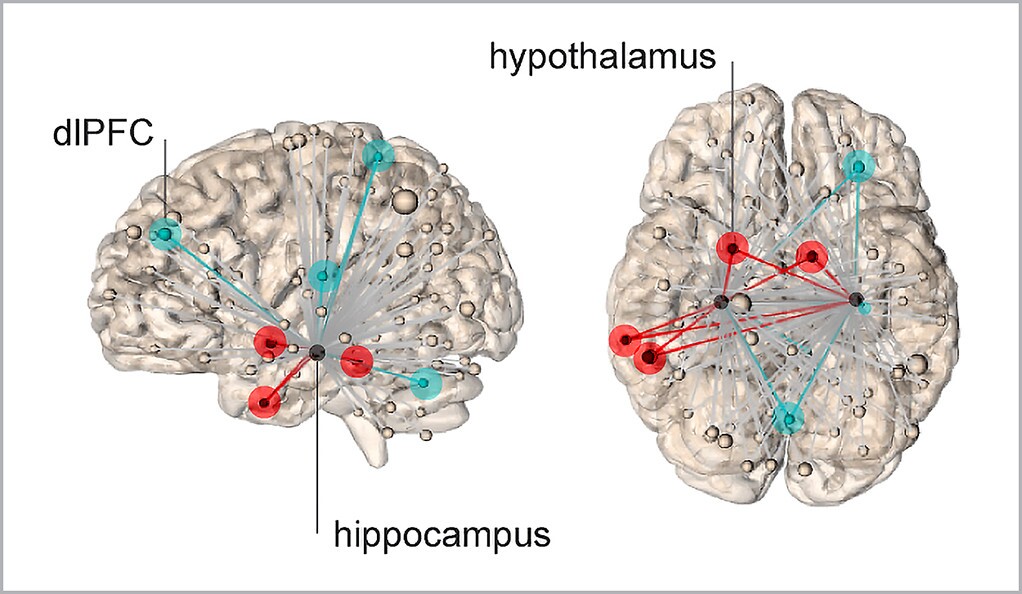

To investigate this question the researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine how the hippocampus communicates with other brain regions upon exposure to acute stress. A number of human subjects were scanned while they watched a series of images. The images alternated between collections of stressful and threatening pictures, such as dirty toilets or violent dogs, and neutral or relaxing images, such as pictures of nature. Throughout the process all subjects also rated their subjective feelings of stress upon viewing the images.

Interestingly, the study found the more subjectively stressed a person felt, the more active neural connections were between the hippocampus and hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is the brain region responsible for releasing glucocorticoids, a hormone that plays a role in physiological stress responses.

However, the study also discovered when subjects reported lower levels of stress sensations, upon viewing particularly threatening images, higher levels of activity were detected between the hippocampus and the dorsal lateral frontal cortex. The researchers ultimately were able to effectively predict a person’s subjective sensation of stress before they even felt it, by measuring acute hippocampal connectivity with these other brain regions.

The implications of the discovery are compelling. Senior author on the study Rajita Sinha says future research could investigate ways to modulate neural connectivity, helping those who are more paralyzed from extreme sensations of stress by altering their hippocampal signaling.

“These findings may help us tailor therapeutic intervention to multiple targets, such as increasing the strength of the connections from the hippocampus to the frontal cortex or decreasing the signaling to the physiological stress centers,” says Sinha.

Elizabeth Goldfarb, lead author on the study, suggests it may be a memory-recall process that helps individuals moderate their acute sensations of stress. The hypothesis is, in the face of extreme stressful imagery, the hippocampus reaches out to the frontal cortex to offer some kind of memory-recall process to help modulate a subjective stress response.

“Similar to recent findings that remembering positive experiences can lower the body’s stress response, our work suggests that memory-related brain networks can be harnessed to create a more resilient emotional response to stress,” says Goldfarb.

The new study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Yale University