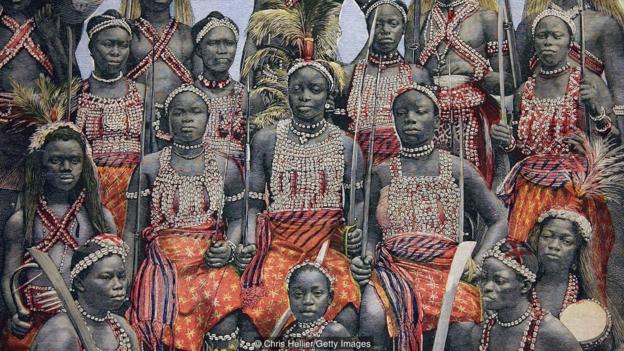

This fierce all-female army was so ruthless that European colonists called them the Amazons after the merciless warriors of Greek mythology.

by Fleur Macdonald –

Actors Chadwick Boseman and Michael B Jordan earned high praise for their roles in the 2018 Marvel film Black Panther. But for me, the real stars were the Dora Milaje, the special forces unit of the fictional Kingdom of Wakanda. Fearsome yet principled, these female bodyguards provided the film’s moral compass.

I was thrilled to find out that the inspiration for these powerful women is rooted in reality, and that the descendants of these women still keep their traditions alive.

The inspiration for the Dora Milaje, the all-female special forces unit in the Marvel film Black Panther, is rooted in reality (Credit: Marvel/Disney).

“She is our King. She is our God. We would die for her,” said Rubinelle, choosing her words carefully. The 24-year-old secretary was talking about her grandmother, who was sitting on a bed in one of the front rooms of a house in Abomey, the former capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey and now a thriving city in southern Benin. The elderly woman’s head was adorned with a crown.

I had been granted an audience with Dahomian royalty: a descendant of Queen Hangbe, who according to local legend is the founder of the Amazons, an elite group of female warriors. As her living embodiment, the elderly woman has inherited her name and her authority. Four Amazons were attending to her, sitting on a woven mat on the floor. The room was relatively grand: there was a table and chairs for visitors and, in the corner, sat an old-fashioned television next to a makeshift drinks cabinet.

After indicating that I should prostrate myself before the queen and take a ceremonial sip of water, Rubinelle and her grandmother told me the story of their ancestors.

Queen Hangbe’s attendants are descendants of the Amazons, a unit of elite female warriors (Credit: Fleur Macdonald).

The Dahomey Amazons were frontline soldiers in the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey, a West African empire that existed from 1625 to 1894. Its remnants lie in modern-day Benin, which occupies a sliver of the coast between Nigeria and Togo. Whether conquering neighbouring tribes or resisting European forces, the Amazons were known for their fearlessness. In one of the final battles against the French in 1892 before the kingdom became a French colony, it is said only 17 out of 434 Amazons came back alive.

It was King Ghezo, who ruled over Dahomey from 1818 to 1858, who officially integrated the Amazons into the army. This in part was a practical decision, as manpower was increasingly scarce due to the European slave trade.

The recognition of the Amazons as official soldiers of Dahomey strengthened a duality that was already embedded in the society through the kingdom’s religion, which has since developed into Vodun, now one of Benin’s official religions and the basis of voodoo. An integral legend told of Mawu-Lisa, a male and female god who came together to create the universe. In all institutions, political, religious and military, men would have a female equivalent. The king, however, reigned supreme.

Her legacy lived on through her mighty female soldiers

Historical accounts of the Amazons are notoriously unreliable, though several European slave traders, missionaries and colonialists recorded their encounters with the fearless women. In 1861, Italian priest Francesco Borghero described an army exercise where thousands of women scaled 120m-high thorny acacia bushes barefoot without a whimper. In 1889, French colonial administrator Jean Bayol described witnessing one young Amazon approach a captive as part of her training. “[She] walked jauntily up, swung her sword three times with both hands, then calmly cut the last flesh that attached the head to the trunk… She then squeezed the blood off her weapon and swallowed it.”

Europeans who visited the kingdom in the 19th Century called Dahomey’s female fighters Amazons after the ruthless warriors of Greek mythology. Today, historians refer to them as mino, which can be translated as ‘our mothers’ in the local Fon language. However, Leonard Wantchekon, who was born in Benin and is now professor of politics at Princeton University and founder of the African School of Economics in Cotonou, Benin, claims the contemporary term does not accurately reflect the role the warriors played in Dahomey society. “Mino means witch,” he said.

Europeans named the soldiers Amazons after the ruthless warriors of Greek mythology (Credit: The Picture Art Collection/Alamy).

Today, the role of Queen Hangbe and her Amazons is primarily ceremonial, presiding over religious rituals that take place at the temple near her home. When I asked to take photographs of Queen Hangbe, Pierrette, another Amazon, jumped up to unfurl a ceremonial parasol over her mistress in the dark room. Fabric spelling out ‘Reine Hangbe’ (Queen Hangbe) had been sewn into the fabric using the appliqué technique of Dahomey tradition. A dressmaker, Pierrette designs a new umbrella for her queen every year. Loaded with symbolism, these elaborately decorated parasols once showed status in the Dahomey court.

Queen Hangbe’s umbrella was relatively simple, though in the 18th and 19th Centuries, they were often adorned with the bones of vanquished enemies. Parasols also featured images of birds and animals, as well as the round-headed clubs that Amazons used in battle.

These lethal weapons also feature in carvings on the mud walls of the squat palace buildings. Each king would build a new palace next to his predecessor’s, leaving the former as a mausoleum. Though Behanzin, the last king of the Dahomey Empire, burnt the palaces before the French arrived, a section still stands in Abomey, a rusty Unesco sign hanging limply at the entrance. The bas reliefs show how the Amazons used the clubs, as well as muskets and machetes, to inflict death on enemies. In one dusty cabinet, a horse’s tail springs from a human skull – a trophy brought back by an Amazon for her monarch to use as a fancy fly swatter.

The history of the Kingdom of Dahomey is preserved in the Royal Palaces of Abomey in modern-day Benin (Credit: ullstein bild/Getty Images).

There has always been a fascination with the Amazons, but its nature seems to be changing. The Black Panther film is responsible, certainly, but Dr Arthur Vido at the University of Abomey-Calavi, who has introduced a new course on the history of women in West Africa, has another theory. “As the status of women is changing in Africa, people want to know more about their role in the past.”

Much of the interest in the Amazons centres on their mercilessness, though Wantchekon dismisses the glorification of their battle exploits. “That’s just what soldiers did,” he said. Instead, Wantchekon is more interested in what the Amazons achieved as veterans.

Where a profession that’s critical for society is dominated by men, well, why don’t we insert a unit of elite women to work side by side with men? To be equal to men

The village where Wantchekon grew up, to the west of Abomey, used to be the site of the Amazons’ training camp. For many years, his aunt looked after an elderly Amazon who had moved to the village after retiring from the army. Villagers still remember the former soldier as “strong, independent and powerful,” Wantchekon said. She challenged village hierarchies and “could do that without any repercussion from the local chief because she was an Amazon”. Her example, Wantchekon thinks, inspired other women, including his mother, to be ambitious and independent.

For this reason, Wantchekon believes the Amazons are still relevant today. “Where a profession that’s critical for society is dominated by men, well, why don’t we insert a unit of elite women to work side by side with men? To be equal to men.” For Wantchekon, it is not their strength or military prowess that made the Amazons extraordinary, but rather their capacity as role models. Marvel Studios can see the appeal: a spin-off devoted to the Dora Milaje is in the works.

As I took my leave of Queen Hangbe, Rubinelle rose to shake my hand, towering over me and looking me firmly in the eye. Driving away, I saw newly erected statues of Amazons along the road. They stood tall and broad-shouldered, and looked a lot like Rubinelle.

(Source of this article, and for more from BBC Travel, visit: https://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20180826-the-legend-of-benins-fearless-female-warriors/)