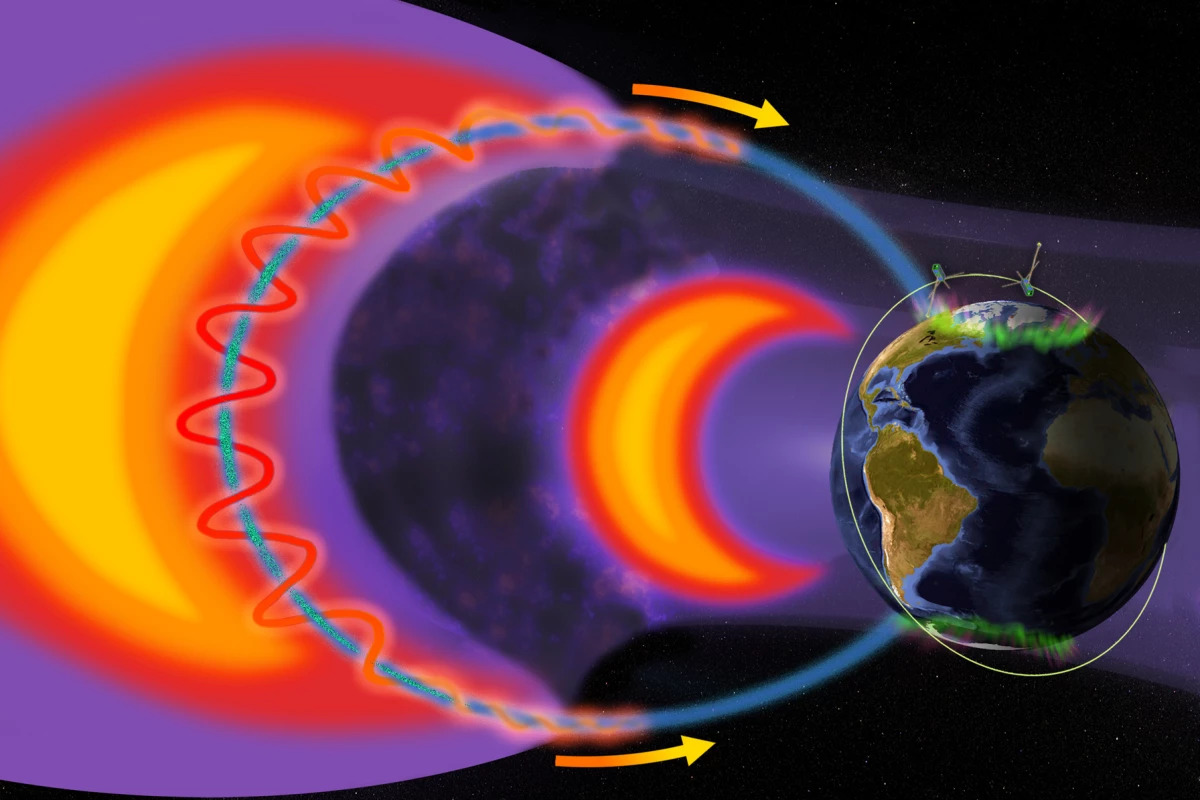

The ELFIN satellites have detected superfast electron rains pouring down onto Earth thanks to whistler waves in the magnetosphere. NASA, Emmanuel Masongsong/UCLA

The ELFIN satellites have detected superfast electron rains pouring down onto Earth thanks to whistler waves in the magnetosphere. NASA, Emmanuel Masongsong/UCLA

– Michael Irving

2022 Mar 30 –

Electron rains aren’t a new thing, nor are they particularly problematic most of the time. Electrons and other charged particles collect in the Earth’s magnetosphere, bouncing back and forth between the north and south poles. Solar wind and storms can knock some of them loose, sending them raining down into Earth’s atmosphere where they can contribute to aurora.

But in the new study, the UCLA researchers discovered a new mechanism that creates larger downpours of electrons than previously known. The culprit is what’s known as “whistler waves,” a kind of electromagnetic wave that washes through the plasma in the magnetosphere. These waves can energize the electrons in that plasma, causing them to speed up and fall out of the radiation belts. The resulting rains move much faster and in greater volumes than the usual electron rains.

The team made the observations using ELFIN, a pair of microsatellites each about the size of a loaf of bread. From their position in low-Earth orbit, the ELFIN satellites can detect and measure electron rains, while the team measured whistler waves using data from NASA’s THEMIS satellites. Combining the two datasets indicated a clear link between whistler waves and superfast electron rains. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these downpours occurred more often during solar storms.

So far, these superfast electron rains aren’t accounted for in existing models and predictions for space weather. But factoring them in is important, the team says, because these events can disrupt satellites in low orbit, damage spacecraft passing through, or affect the health of astronauts.

“Although space is commonly thought to be separate from our upper atmosphere, the two are inextricably linked,” said Vassilis Angelopoulos, principal investigator at ELFIN. “Understanding how they’re linked can benefit satellites and astronauts passing through the region, which are increasingly important for commerce, telecommunications and space tourism.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: UCLA

–

–

Please keep comments to less than 150 words. No abusive material or spam will be published.

–