Fast-moving floodwater obliterated sections of major roads through Yellowstone National Park in 2022. Jacob W. Frank/National Park Service

–

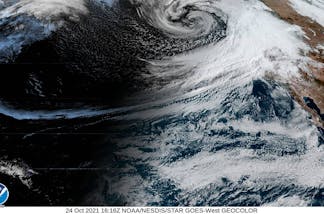

In mid-June 2022, storms dumped up to 5 inches of rain over three days in the mountains in and around Yellowstone National Park, rapidly melting snowpack. As the rain and meltwater poured into creeks and then rivers, it became a flood that damaged roads, cabins and utilities and forced more than 10,000 people to evacuate.

The Yellowstone River shattered its previous record and reached its highest water levels recorded since monitoring began almost 100 years ago.

Although floods are a natural occurrence, human-caused climate change is making severe flooding events like this more common. I study how climate change affects hydrology and flooding. In mountainous regions, three effects of climate change in particular are creating higher flood risks: more intense precipitation, shifting snow and rain patterns and the effects of wildfires on the landscape.

Warmer air leads to more intense precipitation

One effect of climate change is that a warmer atmosphere creates more intense precipitation events.

This occurs because warmer air can hold more moisture. The amount of water vapor that the atmosphere can contain increases by about 7% for every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) of increase in atmospheric temperature.

Research has documented that this increase in extreme precipitation is already occurring, not only in regions like Yellowstone, but around the globe. The fact that the world has experienced multiple record flooding events in recent years – including catastrophic flooding in Australia, Western Europe and China – is not a coincidence. Climate change is making record-breaking extreme precipitation more likely.

–

Extreme storms get wetter as temperatures rise

As temperatures rise, the intensity of storms increases, the IPCC’s latest assessment report shows. The chart shows how much wetter heavy one-day storms that historically occurred about once every 10 years are likely to become as temperatures rise.

102030%

The latest assessment report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] shows how this pattern will continue in the future as global temperatures continue to rise.

More rain, less snow

In colder areas, especially mountainous or high-latitude regions, climate change affects flooding in additional ways.

In these regions, many of the largest historical floods have been caused by snowmelt. However, with warmer winters due to climate change, less winter precipitation is falling as snow, and more is falling as rain instead.

This shift from snow to rain can have dramatic implications for flooding. While snow typically melts slowly in the late spring or summer, rain creates runoff that flows to rivers more quickly. As a result, research has shown that rain-caused floods can be much larger than snowmelt-only floods, and that the shift from snow to rain increases overall flood risk.

The transition from snow to rain is already occurring, including in places like Yellowstone National Park. Scientists have also found that rain-caused floods are becoming more common. In some locations, the changes in flood risk due to the shift from snow to rain could even be larger than the effect from increased precipitation intensity.

–

The highest flow rate in the Yellowstone River each year

The Yellowstone River’s flow rate during destructive flooding in June 2022 shattered its previous record annual high. The line shows the trend over time.

Changing patterns of rain on snow

When rain falls on snow, as happened in the recent flooding in Yellowstone, the combination of rain and snowmelt can lead to especially high runoff and flooding.

In some cases, rain-on-snow events occur while the ground is still partially frozen. Soil that is frozen or already saturated can’t absorb additional water, so even more of the rain and snowmelt run off, contributing directly to flooding. This combination of rain, snowmelt and frozen soils was a primary driver of the Midwest flooding in March 2019 that caused over US$12 billion in damage.

While rain-on-snow events are not a new phenomenon, climate change can shift when and where they occur. Under warmer conditions, rain-on-snow events become more common at high elevations, where they were previously rare. Because of the increases in rainfall intensity and warmer conditions that lead to rapid snowmelt, there is also the possibility of larger rain-on-snow events than these areas have experienced in the past.

–

In lower-elevation regions, rain-on-snow events may actually become less likely than they have been in the past because of the decrease in snow cover. These areas could still see worsening flood risk, though, because of the increase in heavy downpours.

Compounding effects of wildfire and flooding

Changes in flooding are not happening in isolation. Climate change is also exacerbating wildfires, creating another risk during rainstorms: mudslides.

Burned areas are more susceptible to mudslides and debris flows during extreme rain, both because of the lack of vegetation and changes to the soil caused by the fire. In 2018 in Southern California, heavy rain within the boundary of the 2017 Thomas Fire caused major mudslides that destroyed over 100 homes and led to more than 20 deaths. Fire can change the soil in ways that allow less rain to infiltrate into the soil, so more rain ends up in streams and rivers, leading to worse flood conditions.

–

With the uptick in wildfires due to climate change, more and more areas are exposed to these risks. This combination of wildfires followed by extreme rain will also become more frequent in a future with more warming.

Global warming is creating complex changes in our environment, and there is a clear picture that it increases flood risk. As the Yellowstone area and other flood-damaged mountain communities rebuild, they will have to find ways to adapt for a riskier future.

–

–

Partners

Colorado State University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

We need your help

The Conversation is a nonprofit organization working for the public good through fact- and research-based journalism. Nearly half of our budget comes from the support of universities, and higher education budgets are under unprecedented strain. Your gift can help us keep doing our important work and reach more people. Thank you.

Beth Daley

Editor and General Manager

–

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 148,700 academics and researchers from 4,417 institutions.

C K. Worthing

The regression line in the figure “The highest flow rate in the Yellowstone River each year” is not totally convincing. It seems that only a few exceptional years, not more frequent but more rainy, explain the regression line. Especially since the early years (1930s) seem to be abnormally low in rainfall.

Richard Haywood

A consequence of a warming planet https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jul/05/within-five-minutes-everything-changed-town-mourns-victims-of-glacier-tragedy