Participants in the Indigenous Peoples Of the Americas Parade in New York City, 2022 Oct 15. Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

–

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@TheConversation.Com.

What makes someone Indigenous? – Artie, age 9, Astoria, New York

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

You may have heard that in school. The rhyme makes it easier to remember that 1492 was the year when an Italian explorer named Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain [España] and landed in a chain of islands near modern-day Florida called the “West Indies.”

Europeans called the enormous land mass that we now know as North and South America the “New World” because, before the very late 15th century, nobody on the east side of the Atlantic Ocean even knew it existed. A few Viking explorers had reached the Americas hundreds of years earlier, but little is known about their visits.

From Europeans’ standpoint, Columbus had discovered something new. But for millions of Native, or Indigenous, people who already lived there, the “New World” wasn’t new at all.

Connected to place

In the most basic terms, whether a person or a group of people is Indigenous comes down to where their ancestors lived and how long they lived there.

People are considered Indigenous to a certain place when their ancestors existed and thrived in that place since time immemorial – basically, for longer than anyone can remember, or before people started keeping written historical records.

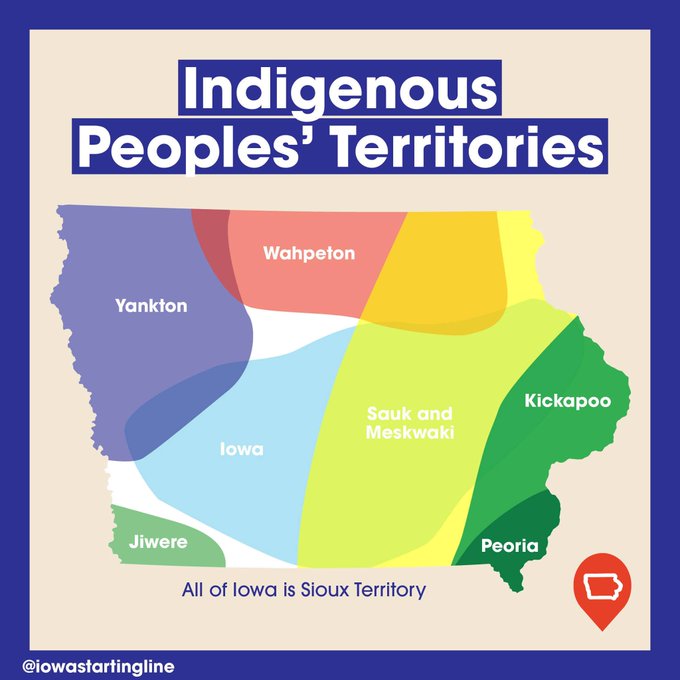

Indigenous peoples are the original inhabitants of a certain area. Their villages and territories were the first ones to be established in a particular place and were around long before modern cities, states or countries existed.

Cultural identity

There are an estimated 476 million Indigenous people in about 5,000 Indigenous groups spread out all over the world. They live in almost every corner of the globe, including the frozen Arctic in northern Canada and Alaska, the plains of the U.S., the mountains and rain forests of Latin America, the islands of the Pacific Ocean, and throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, New Zealand and just about anywhere else that people live – including major cities.

Each of those unique groups has deep, historical connections to a particular part of the world. And their experiences have produced just as many unique cultures.

Where you live – especially if your family has lived there for centuries – can have a huge impact on your way of life. It shapes things like the type of home you live in, the food you eat, how you cook and even things like how and who you worship in your religion.

For instance, my father’s Indigenous ancestry comes from the Comanche, Kiowa and Cherokee tribes. The Comanches traveled around a lot, across a wide expanse of land from Canada in the north all the way down to the jungles of South America.

They learned to follow the migration of buffalo, which was their main source of food. And they developed techniques that made traveling easier, such as creating mobile shelters called tepees that could be easily set up, broken down and carried from place to place.

My mother grew up in an Indigenous community known as Taos Pueblo. The people of Taos Pueblo stayed year-round in the same area of northern New Mexico, which was home to vast mountain ranges and flowing rivers. Since the people of Taos Pueblo did not have to move around as much, they built large buildings out of adobe, or baked mud bricks, that were several stories tall and could not be moved.

While being Indigenous is a matter of ancestry and place, different Indigenous groups have their own cultures, traditions, languages and religions, much as these things may differ from country to country, state to state or even city to city today.

Political identity

Today, being Indigenous does not necessarily mean that your ancestors lived in the same place where you live right now. In fact, throughout history many Indigenous groups were removed from their traditional homelands and forced to live somewhere else.

Most Indigenous groups who were forced off their lands did not want to leave. But settlers from elsewhere saw the lands and resources where Indigenous peoples lived and wanted them for their own countries. Often they used military force to make Indigenous peoples leave their homes.

Many of those groups exist today as a type of government known as a tribe or Native nation. There are at least 574 tribes in the U.S. alone. Like any other government, tribal governments make laws about how to live together peacefully, decide what it means to be a good citizen and plan for the future.

Together, those laws form a political community – an understanding about how all members of a Native nation agree to live and treat each other as part of the same Indigenous community.

So while being Indigenous has always been tied very closely to place, today it is also a matter of cultural and political identity. It helps to shape a person’s connection to their community and enables them to understand their place in history.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@TheConversation.Com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

–

- Indigenous

- Identity

- Culture

- Native Americans

- Community

- Indigenous rights

- Displacement

- Indigenous Peoples

- Curious Kids

- Curious Kids US

- Tribes

–

Partners

University of Arizona provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

We need your help

The Conversation is a nonprofit organization working for the public good through fact- and research-based journalism. Nearly half of our budget comes from the support of universities, and higher education budgets are under unprecedented strain. Your gift can help us keep doing our important work and reach more people. Thank you.

Beth Daley

Editor and General Manager

–

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 154,800 academics and researchers from 4,504 institutions.

Terrence Treft

thanks for the interesting article. what a fine piece of writing for curious kids and curious adults alike!

if you would, in a nut shell, what is the status of indigenous people and native tribes in relationship to the federal and state governments, especially as that pertains to the current neo-conservative ideology of sovereign states and states’ rights?