A female P. regius, another of the keen-sighted North American jumping spiders, which only grows to a maximum 0.87 in (22 mm) in size. Depositphotos View gallery – 3 images

A female P. regius, another of the keen-sighted North American jumping spiders, which only grows to a maximum 0.87 in (22 mm) in size. Depositphotos View gallery – 3 images

–

Despite research into methods to mitigate its progression, and medical interventions such as retina and bionic eye transplants, less-invasive treatments and gene therapies, there’s no known way to restore vision once it’s lost.

Scientists have also been exploring the connection between nutrition and AMD, and macular degeneration specialists recommend diets high in antioxidants such as lutein and zeaxanthin, omega-3, zinc, selenium and vitamins E and C to preserve eye health.

Now, a team of researchers has stumbled across an unexpected, left-of-field link between nutrition and eyesight loss that mirrors AMD progression – in the keen eyes of jumping spiders.

Biologists at the University of Cincinnati (UC) found that underfed bold jumping spiders (Phidippus audax) lost light-sensitive photoreceptors, the part of the eye that processes visual cues in the central region of sight. Jumping spiders are known for using their excellent vision to hunt and for accuracy in their trademark leaping abilities.

“You could tell just by looking at them that some of the photoreceptors had died,” said Elke Buschbeck, a professor at UC. “It’s the functional equivalent of the macula in our eyes.”

The photoreceptors are vital for responding to light and initiating the signal pathways to the brain for information processing. They’re also energy intensive, which could hold the connection between the right fuel and if a lack of it could spur on AMD.

“Photoreceptors are energetically costly,” Buschbeck said. “It’s hard to keep up with their energy needs. If you deprive them of nutrition, the system fails.

“What’s interesting is macular degeneration in humans also has evidence of being linked to metabolic processes and difficulty with energy being delivered,” she added.

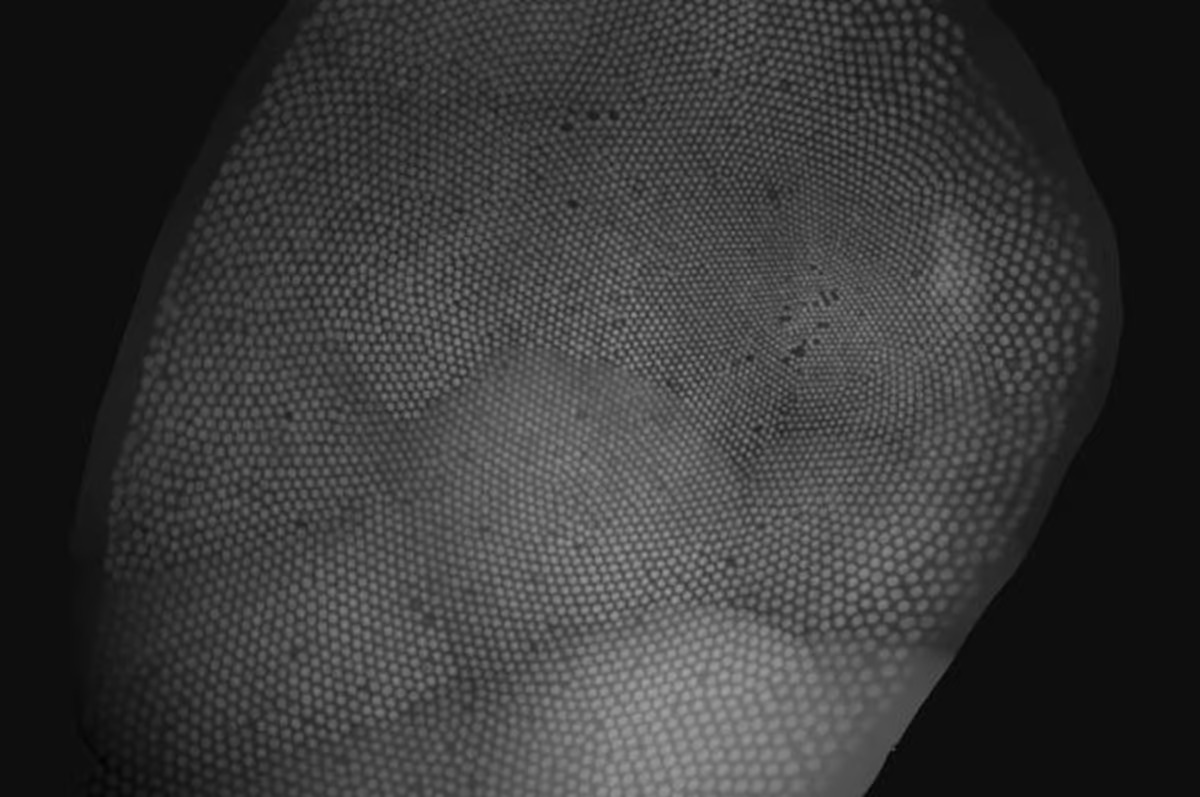

The researchers tested their theory on two groups of spiders, one with adequate nutrition and the other fed half portions. Using a custom-made micro-ophthalmoscope to take photos of the retinas of the spiders, the scientists discovered far more prevalent dark spots in the eyes of the hungry insects, particularly in the region of the retina that had the highest density of them.

The damaged photoreceptors, which look like blacked-out pixels on a screen, appeared to have glitched out due to energy loss, and the scientists believe this is an avenue of study that could form stronger ties between nutrition and the types of cells that need high energy input to keep functioning.

While the scientists were quick to caution that it’s premature to draw direct comparisons between vision loss in spiders and humans, it could present a new avenue of research into a debilitating condition that currently has no cure.

“To be able to say anything about how this may inform treatments in people, first carefully designed studies would need to tease out which exact nutrients are involved, which may depend on environmental conditions and other factors,” said study senior author Annette Stowasser, an assistant professor at UC. “However, that nutrient deprivation can have the shown effect indicates the importance of paying close attention to the effects of nutrients.”

“Wouldn’t it be wild if a breakthrough in macular degeneration treatments for humans was inspired by work on jumping spiders common to backyards across the United States?” said Nathan Morehouse, an associate professor at UC. “Sometimes answers to challenging problems can come from unexpected places.”

The study was published in the journal Vision Research.