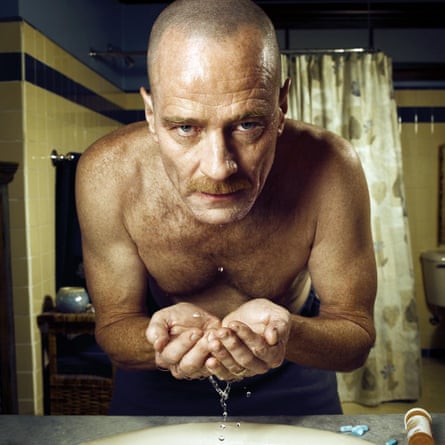

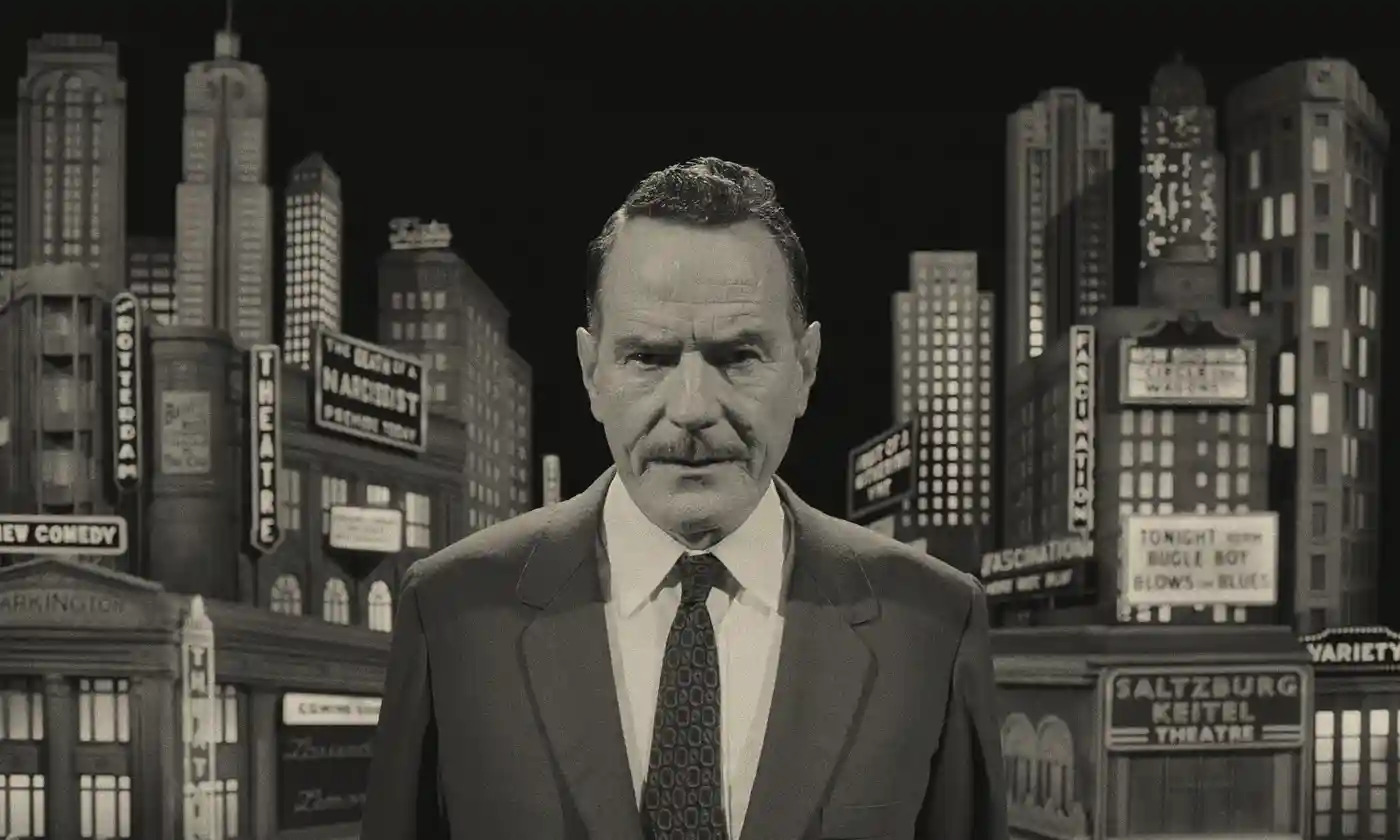

Has he got news for you … Bryan Cranston stars as the Host in Asteroid City. Photograph: Pop. 87 Productions/Focus Features

Has he got news for you … Bryan Cranston stars as the Host in Asteroid City. Photograph: Pop. 87 Productions/Focus Features

–

His role as The Host in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City sees the actor return to the desert. He reflects on how Covid protected his privacy, his secrets to acting success, and how his estranged father tried to cash in on Breaking Bad.

–

“The circus,” says Bryan Cranston, gesturing to the window of his seafront Cannes hotel. He is indicating the film festival fray on the promenade below. The crowds and the cordons; the limousines and the red carpet. He could walk down and join it, but he is happier staying put. “I’ve never been a keen participant of the circus.”

Cranston is in town for the premiere of Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, a light-footed account of “brainiac” students at a stargazer convention. It is the 67-year-old actor’s first visit to Cannes: in part because his greatest triumphs have been on TV, most notably in Breaking Bad; in part, perhaps, because he prefers to avoid the hurly-burly of big events. The publicist suggests cracking open the window to let in the breeze. He must be boiling in his cream suit. His Wyatt Earp mustache may start to wilt. “No, leave it,” he instructs. “The air-con is good.”

Fittingly, Asteroid City positions him adjacent to the action, neatly quarantined in his own private space. Cranston plays the tale’s straight-edged narrator, on hand to introduce the cast and explain the plot’s twists and turns. The bulk of the film plays out in a dust-blown 50s town. Anderson arranges his characters against a salmon-pink desert; every frame resembles a William Eggleston print, and vintage American cars gleam like boiled sweets. Only once does the narrator blunder on to colorful Main Street. “Am I not in this scene?” he asks, briefly stumped, before scarpering back to the safety of his box.

The narrator is your classic elder-statesman role. It makes the most of Cranston’s velvety voice, his air of authority and his confident swagger, like a riverboat gambler. He took his cue, he explains, from the newsreaders of his youth and studied footage of Walter Cronkite and Edward R Murrow to prepare. “The only problem was speed,” he says. “In Wes’s movies, everyone talks very quickly. I don’t think there was any actor on set who didn’t get the same response: ‘Yeah, that’s good. Now much, much faster.’”

He hopes that he nailed it, but occasionally on set he had his doubts. Comedy is a good deal harder than drama, he thinks, because the genre is more fragile and therefore more dependent on tempo and momentum. There were days on Asteroid City when he felt himself lagging, struggling to find the right balance. Probably, that is as it should be. “Frustration is inherent in any production,” he says. “Actually, it’s inherent in any career.”

I am guessing that he is speaking as an expert. His CV, after all, is a testimony to heavy lifting. Cranston has been acting since his early 20s, but spent several decades as a jobbing foot soldier, toiling away in TV sitcoms and little-seen movies. It was OK, he insists, because he was making a living and paying the rent. That was his baseline. Anything beyond that was a bonus.

His father, he tells me, had been a Hollywood workhorse himself. Joseph Cranston acted on TV in Space Patrol, Dragnet and The Red Skelton Hour and wrote B-movie scripts for films I haven’t seen (The Corpse Grinders, The Crawling Hand). Joseph, though, always believed that he was built for better things. Indirectly, he taught his son how not to manage a career.

“My dad wanted to become a star,” he says, emphasizing the word as though it’s draped in tinsel and wrapped in neon. “Which to me is the equivalent of saying that you just want to be rich, without having an idea or a plan of how to acquire wealth. ‘I want to be a star.’ How futile is that? It’s a sign of immaturity, which I would tell him directly if he were still alive.”

Furiously chasing his Hollywood dream, Joseph skipped out on the family when Cranston was 11. The two didn’t meet up for another 10 years. “After that, we got along as best we could. But it’s as if the book of my relationship with my father is missing seven or eight chapters in the middle. You have to leapfrog the plot and you know you’re missing things. What happened? Why?” He shrugs. “So it was never what you’d hope a father-son relationship would be.”

–

The way Cranston sees it, a successful acting career depends on four factors. He checks them off one by one. The first is talent, otherwise what is the point? The next is persistence, followed by its cousin, patience. You need those to stay the course. They see you through the endless knock-backs and the more ridiculous gigs. You hold your nose, do your best and keep going. Eventually, hopefully, you graduate to better work.

“The fourth thing is the intangible one,” he says. “The fourth one is luck. No career is made without a healthy dose of luck, and it’s an entity of its own. You can’t will it to come. You have no idea when it might. It comes when it chooses. Sometimes, not at all.”

This brings us back to Cranston, or to his slightly younger self. By the time he hit 50, he was getting good mileage from a three-quarter-full tank. His turn as the put-upon dad in Malcolm in the Middle had secured his finances. He had also cropped up in Seinfeld, playing the shifty dentist, Tim Whatley, who Jerry suspects has converted to Judaism for the jokes. Cranston says he managed to make Seinfeld laugh at the audition and that this, more than anything, is what got him the job. “But I was only in six episodes. People always think it was more: ‘Oh no, no, it was a lot more than that.’ Like, they know better, like, they’re telling me!”

Seinfeld was fun and Malcolm in the Middle was good. It was Breaking Bad, though, that slotted the last piece into place. Here at last was the reward for all that persistence and patience. Here, finally, was a showcase for the man’s acting talent. In the figure of Walter White, the high-school teacher turned drug kingpin, Cranston created an antihero for the ages; a brilliant chemist who has been thwarted and burns with entitlement and self-pity. It was a character, he says, that was based in part on his dad.

Joseph died in 2014, only a couple of months after Breaking Bad’s final season. One obviously wonders what he made of it all. “Oh, he seemed sincerely happy for me,” Cranston says. “Also, he had a great work ethic. He was always writing, always looking for work. And he did look out for opportunities to take advantage of my position in order to further his career. Hitting up my agency to read his scripts.” He laughs shortly. “So yeah, he was hustling right up to the end.”

The great thing about Breaking Bad was that it could be viewed in two ways, often simultaneously, to the point where ambivalence became the show’s natural state. On the one hand it spun a classic tale of redemption, charting an overlooked man’s audacious climb towards greatness. And on the other it pitched us towards hell, and made us root for a monster who destroys everything that he loves. Even Vince Gilligan, the show’s creator, has since found himself cooling on tragic Walter White. “Like, wait a minute, why was this guy so great?” Gilligan said to the New Yorker last year. “He was really sanctimonious and full of himself. He had an ego the size of California and always saw himself as the victim.”

What about Cranston? Did he like Walter White?

“Well,” he says, grimacing, “I can only answer that question in retrospect, because I didn’t have the luxury of objectivity back then. Did I like Walter White? Now I’m thinking of him as a character. He was a phenomenal character to play. Because of his complexity, his loss of direction, and the emergence of an ego that he hadn’t had the permission to show. Did I like him? I mean, if you ask someone if they like themselves, they’d be like, ‘Yes’. Basically yes.”

–

It sounds as though he’s equating himself with the man that he played. “Well, yeah. Because at the time you’re so in it. You’re so subjective. You’re not seeing how other people perceive you.” He scratches his mustache. “I think he’d say – I’d say – that he tried to be a good person.”

One downside with luck is that people tend to ride it for too long. That was the problem with ill-starred White, who had his chance to get out once he had safely banked his first fortune. Possibly it was also an issue for Cranston Sr, who regarded his son’s lucky streak as his own golden ticket. If there is a last essential to any successful career, it may be the ability to quit when you’re ahead. Cash your chips and bow out. Leave the public wanting more.

In a couple of years, Cranston will be 70. This, he has said, might be a good point to sit back and take stock. He would like to spend more time with his wife, Robin Dearden. He wants to read some big novels and regain some sense of privacy.

His impending birthday is one catalyst. Covid was another. Lockdown, he says, taught him the value of home and of a different way of being. For the first time in years he was able to walk about incognito. “This was the great thing about Covid,” he tells me. “And I don’t mean to say that in a flippant way, because it was also devastating to many families. But it taught us cohesiveness, and it taught us to wear masks. That’s been a healthy development. Also, an attractive addendum to my wardrobe. It means I can walk down the street in my mask, hat and glasses and not be recognized. Which is a nice thing. I’d rather not give that up.”

Anonymity and obscurity: that’s what he’s craving today. It appears that the circus will have to proceed without him for a spell. “Obscurity.” He laughs. “Yeah, I like that. Yes, please.”

–

–

Your support will enhance this work, investing in journalism that’s always free from commercial or political interference. Give just once from $1, or better yet, power us every month with a little more. Thank you!

Topics

Most viewed

Most viewed