For conventional immunotherapy, doctors extract immune cells from a patient, genetically engineer them to be more effective at fighting cancer, then infuse them back into the patient so they can get to work. While it has shown promise against some types of cancer, immunotherapy is a costly and risky procedure that can take weeks or months, which isn’t ideal given timeliness is key to many cases.

Ideally, immunotherapy would be universal and in a form that could be mass-produced, distributed and stored in hospitals around the world, ready to be administered to patients on demand like other drugs. And in the new study, UCLA scientists may have found a path towards that goal.

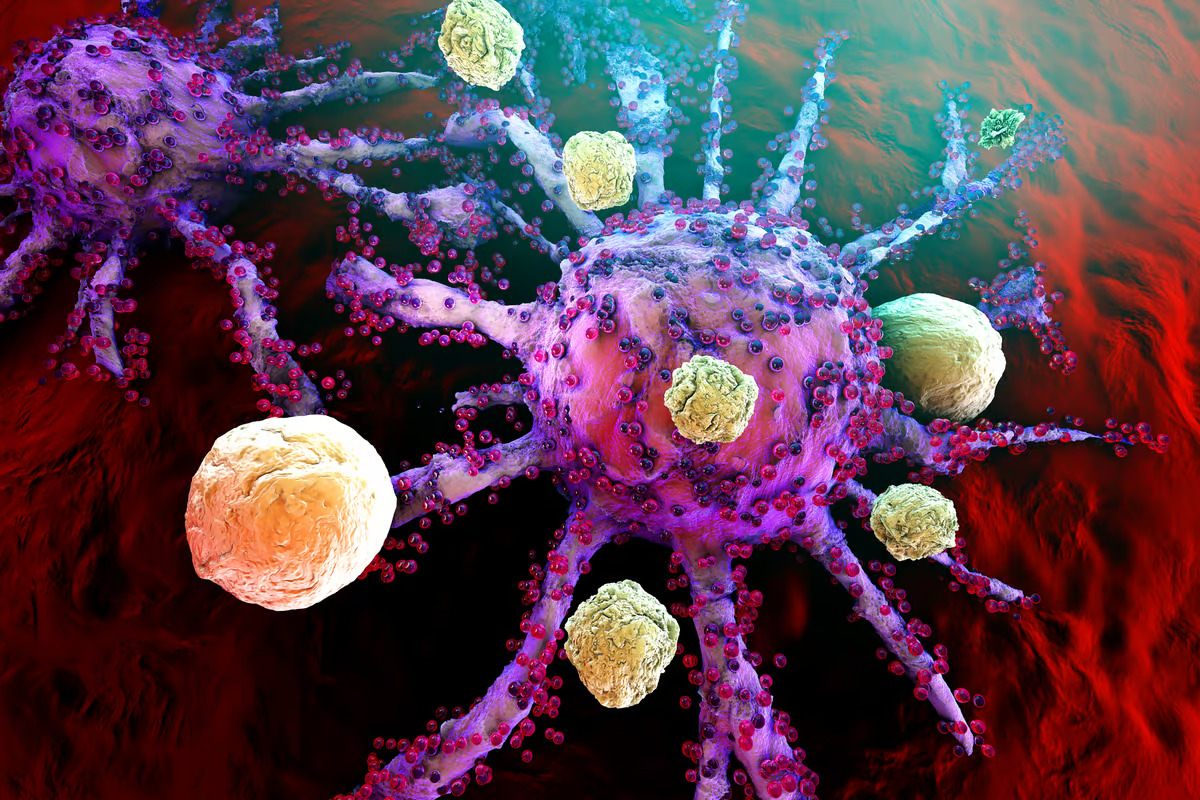

The team focused on gamma delta T cells, a relatively rare type of immune cell that has previously shown promise in cancer immunotherapy. One of their most appealing features is that they don’t need to be sourced from the same patient – they can be administered from donors without triggering immune rejection. However, they do have variable effectiveness.

In this case though, the researchers identified a biomarker that helps them pick out the best candidates from donors – a surface protein called CD16. These gamma delta cells were then engineered with two components that help them hunt cancer – chimera antigen receptors (CAR) and interleukin-15 (IL-15).

“These CD16-high gamma delta T cells exhibit unique characteristics that increases their ability to recognize a tumor,” said Lili Yang, senior author of the study. “They demonstrate heightened levels of effector molecules and are equipped with the ability to engage in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against cancer cells. We found by using CD16 as a biomarker for donor selection we can improve their anti-cancer properties.”

The team then tested the technique on models of ovarian cancer, including human cells in lab dishes and in mice. In the animal tests, all five mice that received gamma delta cells with both CAR and IL-15 saw complete remission through the full 180-day experiment. By contrast, all five control mice died around day 70 from their cancer, while those that received regular CAR T-cell therapy alone died soon after from deadly immune responses. In mice receiving gamma delta T cells engineered with CAR but without the IL-15 component, two out of five mice survived the whole test, indicating both components are most effective together.

“The results of this research shed light on the promising feasibility, therapeutic potential, and remarkable safety profile of these engineered CD16-high gamma delta T cells,” said Yang. “We hope this can be a viable therapeutic option for cancer treatment in the future.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications. Source: UCLA

–