–

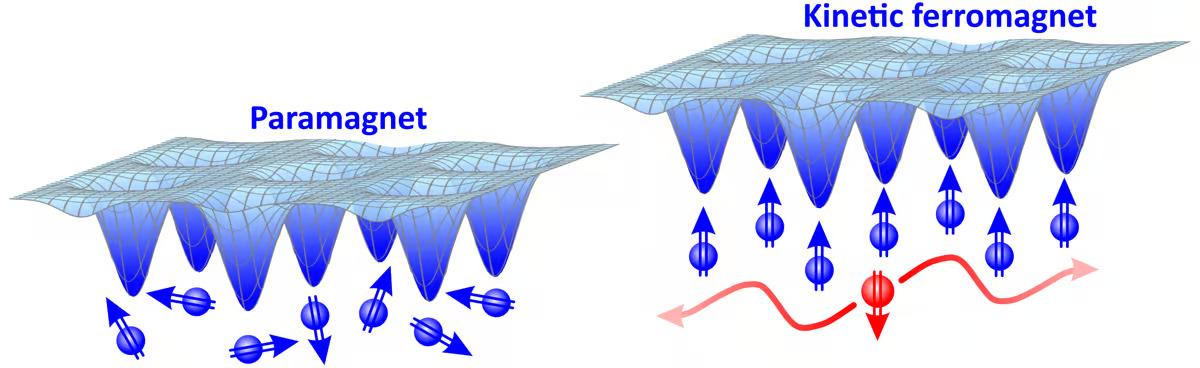

The most commonly known form of magnetism – the kind that sticks stuff to your fridge – is what’s called ferromagnetism, which arises when the spins of all the electrons in a material point in the same direction. But there are other forms such as paramagnetism, a weaker version that occurs when the electron spins point in random directions.

In the new study, the ETH scientists discovered a strange new form of magnetism. The researchers were exploring the magnetic properties of moiré materials, experimental materials made by stacking two-dimensional sheets of molybdenum diselenide and tungsten disulfide. These materials have a lattice structure that can contain electrons.

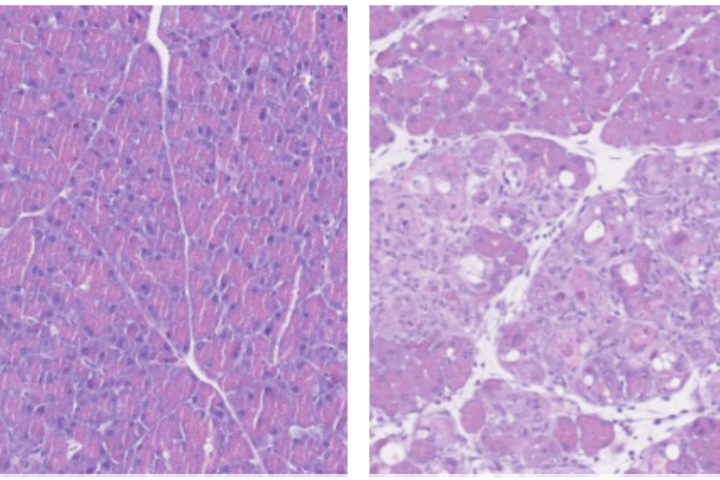

To find out what type of magnetism these moiré materials possessed, the team first “poured” electrons into them by applying an electrical current and steadily increasing the voltage. Then, to measure its magnetism, they shone a laser at the material and measured how strongly that light was reflected for different polarizations, which can reveal whether the electron spins point in the same direction (indicating ferromagnetism) or random directions (for paramagnetism).

Initially the material exhibited paramagnetism, but as the team added more electrons to the lattice it showed a sudden and unexpected shift, becoming ferromagnetic. Intriguingly, this shift occurred exactly when the lattice filled up past one electron per lattice site, which ruled out the exchange interaction – the usual mechanism that drives ferromagnetism.

“That was striking evidence for a new type of magnetism that cannot be explained by the exchange interaction,” said Ataç Imamoğlu, lead author of the study.

The team proposed a different mechanism: as more than one electron enters the lattice sites, they pair up into particles called “doublons,” which end up filling the whole lattice through quantum tunneling. As they do however, the electrons will minimize their kinetic energy, which they do by aligning their spins, therefore producing ferromagnetism. This “kinetic magnetism” has been theoretically predicted for decades but not previously observed in solid materials.

The researchers plan to investigate the phenomenon more closely, including whether it can be achieved at higher temperatures. After all, for this experiment the material had to be cooled down to a fraction above absolute zero.

The research was published in the journal Nature. Source: ETH Zurich

–