The Giza pyramids on the outskirts of Cairo have always made people wonder: how were such incredible structures built with nothing but human and animal muscle for power? Depositphotos View 4 Images –

The Giza pyramids on the outskirts of Cairo have always made people wonder: how were such incredible structures built with nothing but human and animal muscle for power? Depositphotos View 4 Images –

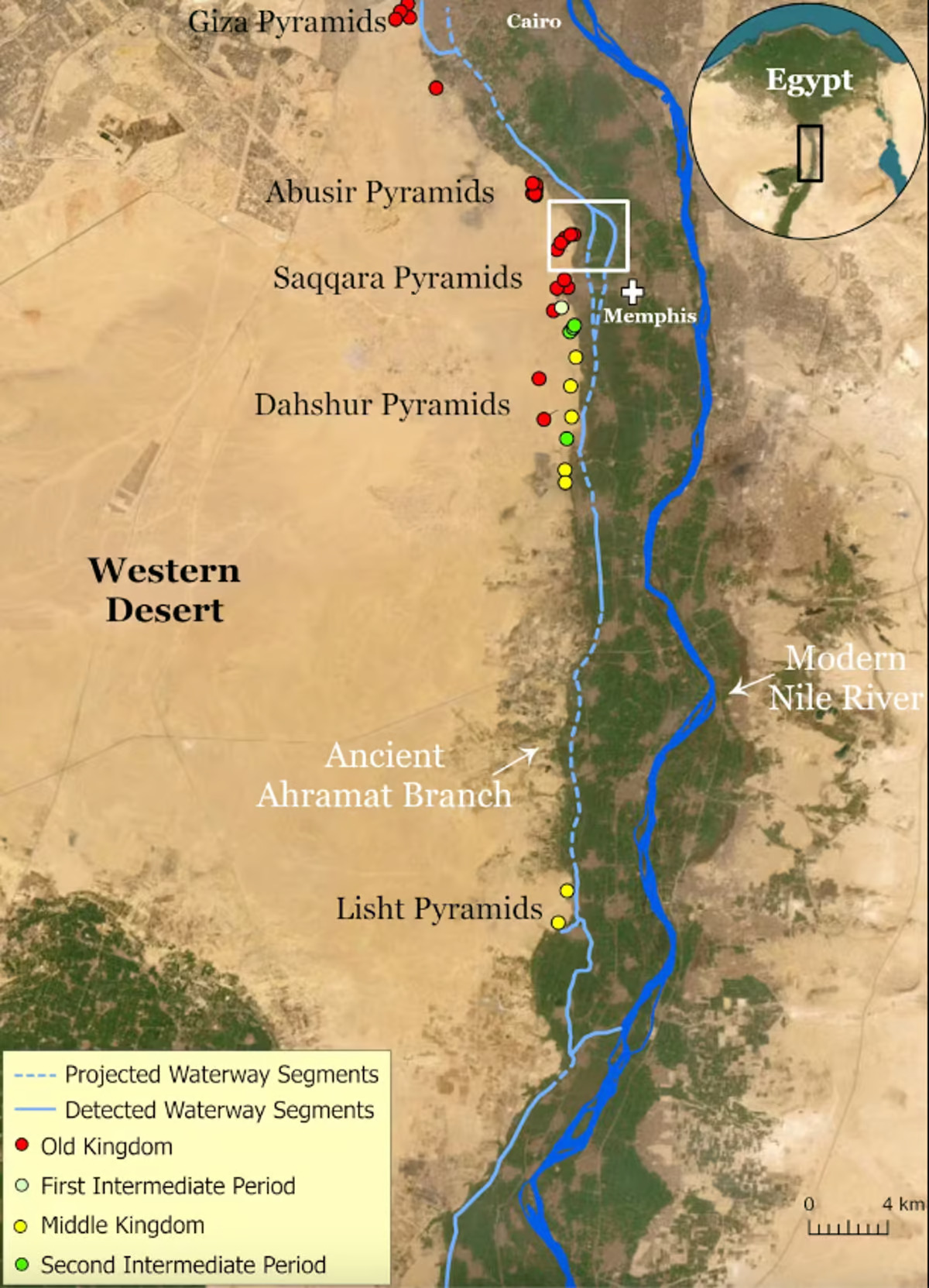

At least, it is currently. A new study suggests that the river was once much closer, but this branch has long since dried up. Using a combination of satellite imagery, geophysical surveys and analysis of sediment samples, the researchers claim to have now mapped out this ancient river branch. They propose the name “Ahramat,” which means pyramids in Arabic.

According to the study, the Ahramat branch extended about 64 km (40 miles) in a north-south direction, roughly parallel to the modern Nile but between 2.5 and 10.25 km (1.6 and 6.4 miles) west of it. It was between 2 and 8 m (6.6 and 26.2 ft) deep, and 200 to 700 m (656 to 2,297 ft) wide, which are similar dimensions to the current river.

Importantly, this old man river seems to have weaved its way past dozens of pyramid sites. Many of them had causeways that end in small structures right where the riverbanks of the Ahramat branch were proposed to have been, suggesting these were acting as docks.

“Many of us who are interested in ancient Egypt are aware that the Egyptians must have used a waterway to build their enormous monuments, like the pyramids and valley temples, but nobody was certain of the location, the shape, the size, or proximity of this mega waterway to the actual pyramids site,” said Professor Eman Ghoneim, lead author of the study. “Our research offers the first map of one of the main ancient branches of the Nile at such a large scale and links it with the largest pyramid fields of Egypt.”

–

So what happened to the Ahramat? The short answer is time – it’s been well over 2,000 years since the last pyramid was built in the area, and that’s plenty of time for the river to migrate eastward. Constant winds depositing sand into the channel could have dried it up, floods could have deposited other sediments into it, or plate tectonics could have diverted it towards its current path.

The discovery could help paint a more accurate picture of life in ancient Egypt, add context to unexplained structures or texts, and could direct teams to new sites for archeological excavations.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Sources: University of North Carolina Wilmington, The Conversation, Nature

Tags