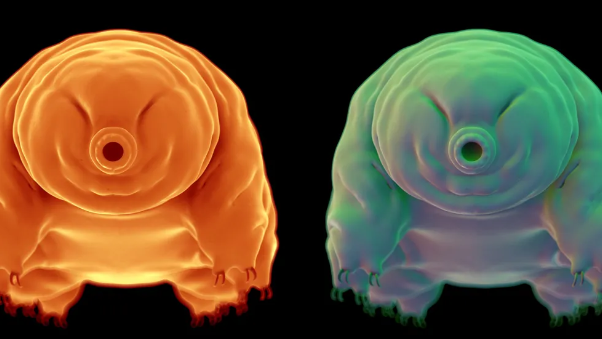

The tardigrade, also known as the moss piglet or water bear, is a bizarre, microscopic creature that looks like something out of a Disney nightmare scene: strange but not particularly threatening. The pudgy, eight-legged, water-borne creature appears to be perpetually puckering. It’s the farthest thing from what you’d expect an unstoppable organism to look like.

Yet, water bears can withstand even the vacuum of space, as one experiment showed. A sort of microscopic Rasputin, tardigrades have been frozen, boiled, exposed to extreme doses of radiation, and remarkably still survive. How they do this has been a mystery to science, until now.

Being a water-borne creature, scientists in this experiment examined how it survived desiccation, or being completely dried out. When it senses an oncoming dry period, the critter brings its head and limbs into its exoskeleton, making itself into a tiny ball. It’ll stay that way, unmoving, until it’s reintroduced into water.

It’s this amazing ability that piqued Thomas Boothby’s interest. He’s a researcher at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Boothby told The New York Times, “They can remain like that in a dry state for years, even decades, and when you put them back in water, they revive within hours.” After that, “They are running around again, they are eating, they are reproducing like nothing happened.”

Originally, it was thought that the water bear employed a sugar called trehalose to shield its cells from damage. Brine shrimp (sea monkeys) and nematode worms use this sugar to protect against desiccation, through a process called anhydrobiosis. Those organisms produce enough of the sugar to make it 20% of their body weight.