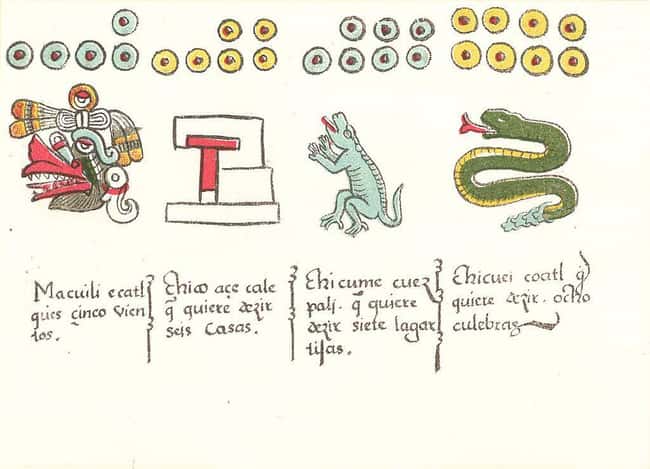

The Aztec, a collective of Mesoamericans who thrived from the 14th to the 16th centuries, were the inheritors of ancient cultural traditions from their Olmec, Mayan, and Toltec predecessors. Aztec hygiene practices reflected earlier practice, continuing a dedication to cleanliness and purity.

When Spanish conquerors first encountered the Aztec peoples during the early 16th century, they were amazed by their techniques for keeping themselves and their surroundings clean. A stark contrast to European practices at the time, the Aztec empire went to great lengths to provide clean water to the masses, rid the air of perceived pollutants, and use natural ingredients to promote health and hygiene. [And, of course ALL of their food was Organic!]

Interwoven with physical and spiritual concerns and considerations, Aztec personal hygiene exceeded expectations of contemporaries and modern observers alike.

They Had Intricate Canal Systems To Transport Clean Potable Water Around Communities

The Aztec peoples were aware of how important water was to all aspects of life, a consideration that contributed to the development of a canals system in the empire’s major cities. In Tenochtitlán, for example, canals not only supplied residents with water, they were also built for movement. Conquistador Hernán Cortés commented that Tenochtitlán was big with wide and narrow streets alongside “half canals where they paddle their canoes.”

Canals that brought fresh water for personal use were lined with plaster, matched by accompanying networks to remove human waste and other detritus. Cortés noted:

Along one of the causeways to this great city run two aqueducts made of mortar. Each one is two paces wide and some six feet deep, and along one of them a stream with very good fresh water, as wide as man’s body, flows into the heart of the city and from this they all drink. The other, which is empty, is used when they wish to clean the first canals.

Canals and aqueducts effectively kept fresh and salt water separate, essential for both individual use and irrigation purposes.

Many Aztec Homes Were Equipped With Steam Baths Called Temazcal

Another benefit of the extensive water system in Aztec cities was the inclusion of baths in private homes. While most Aztecs took cold baths, they also participated in steam baths for ritual purposes.

An Aztec temazcal was a steam lodge – an enclosure with no windows that featured a heated floor dashed with cold water – built in accordance with long-standing Mesoamerican practice. A temazcal was used for purification of the body after physical conflict to aid in healing, cure an illness, or serve as a site for women to bear children.

The goddess of the steam bath was Temazcalteci, a deity whose image was kept on display nearby. Tlazolteotl, the Filth Goddess, protected the entrance to the temazcal, overseeing the process by which people rid themselves of physical and spiritual grime.

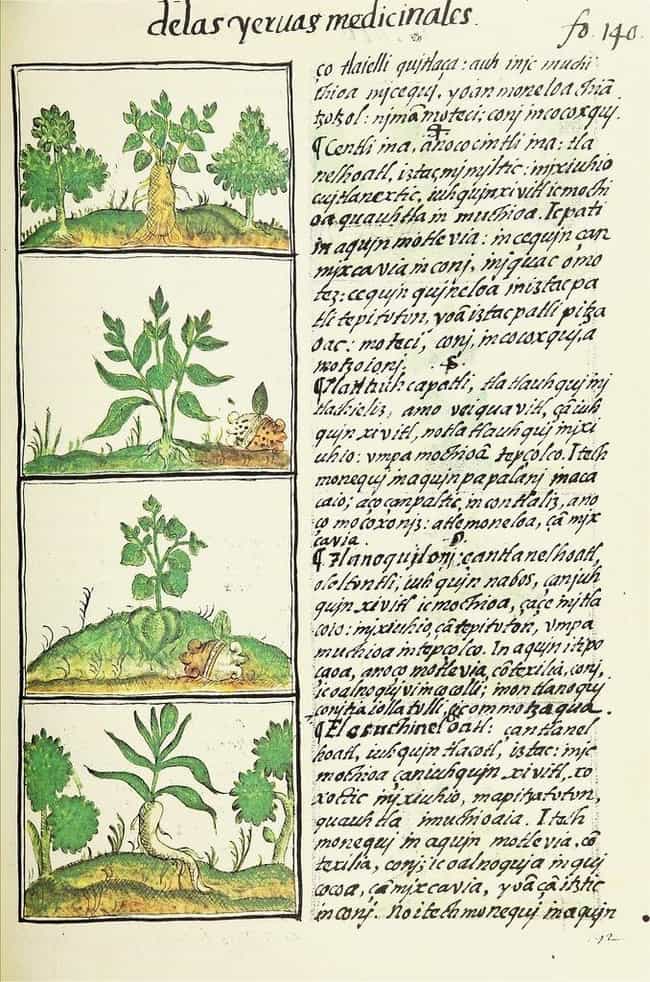

Aztecs Created Natural Soaps And Detergents From Several Local Plants

Aztecs didn’t have soap in the modern sense of the word, but they did embrace the cleansing properties of numerous plants. Roots and fruit from the copalxocotl, called the “soap tree” by the Spanish, produced a lather that could be used to clean the body and clothing alike. The xiuhamolli, also called the amolli, plant had similar properties.

This additional plant, the amolli, was described as, “long and narrow like reeds. It has a shoot; its flower is white. It is a cleanser. The large, the thick [roots] remove one’s hair, make one bald; the small, the slender ones are cleansers, a soap. They wash, they cleanse, they remove the filth.”

The general population during the month of Atemoztli – the 16th month of the solar calendar during which the rains fell by the grace of Tlaloc – and merchants who were traveling for long periods of time often avoided bathing their hair, body, and clothing with the detergent-like natural byproducts as a sign of sacrifice and penance. Similarly, women didn’t wash their faces while men were away fighting. The value of cleanliness was practical and ritualistic. Sacrificial prisoners were even given a bath before they met their end.

They Used Perfumes And Deodorants To Eliminate Foul Odors

According to the Badianus Manuscript, an herbal text from 1552, Aztecs had acute concern for underarm odor:

When smelly and goaty, let him enter a very well prepared bath and there wash the armpits thoroughly; coming out let him also bathe; for this take the [pulverized] plants chiyavaxihuitl, a human and a dog’s bone recently removed from the body, and the juice of all well smelling flowers and plants, with which the hircine odor will be dispelled.

Aztecs also applied deodorants to keep body odor away, using ingredients like copal gum, amber oil, and balsam oil. Women wore perfume, presumably similar to the concoction applied to sick and injured individuals. To overcome “the fetid odor of the infirm,” patients were anointed with a perfume made of flowers, pine needles, and fruit.

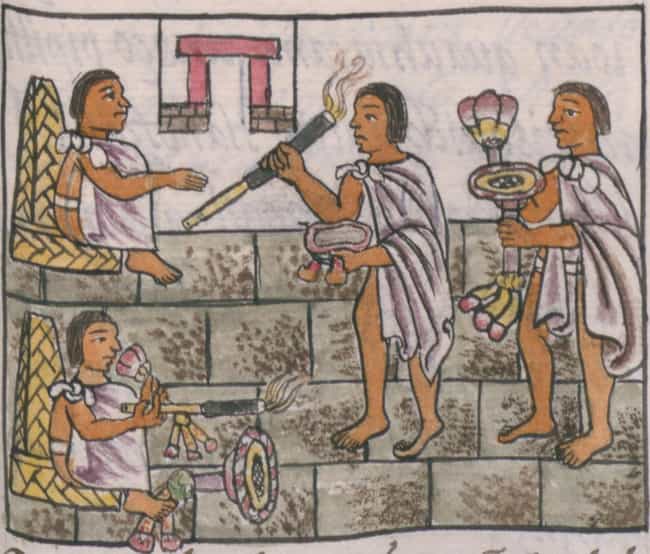

The Aztec burned incense as well, especially priests during religious rituals.

A Clean Face And Clean Clothes Were Essential For Maintaining Purity And Finding A Husband

Remaining clean and pure was the ideal way to find a husband, according to the Florentine Codex, a work by Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún from the 16th century. As one of the few firsthand accounts of Aztec society, the Codex contains insights into cultural traditions in the Aztec world, including this guidance a father offers to his young daughter:

[In the morning] wash your face, wash your hands, clean your mouth… Listen to me, child: Never make up your face nor paint it; never put red on your mouth to look beautiful. Make-up and paint are things that light women use – shameless creatures. If you want your husband to love you, dress well, wash yourself, and wash your clothes.

According to Sahagún, courtesans – women who dressed and groomed themselves “in order to please” – used makeup and perfumes, including “a yellow cream called axin, which gives her a dazzling complexion; and sometimes, being a loose, lost woman, she puts on rouge.”

In truth, women did often wear some makeup, although in moderation. The most common cosmetic was axin, a yellow mud of sorts spread on the skin.

Health Care On The Front Lines Was Praised By Spanish Observers

According to a contemporary chronicle, “Aztec [field] surgeons tended to their wounded skillfully and healed them faster than did the Spanish surgeons.”

The care administered on the field carried over to everyday life. Priests and healers practicing surgeries and bloodletting rituals to promote health also distributed treatments made out of oils, herbs, and other natural products to heal cuts of all kinds.

Aztec healers trained in using herbal remedies to treat everything from headaches to coughs to low-grade infections. For example, juice from the nopal cactus fruit – the tuna – was used to reduce swelling, and bark from the ylin tree was mixed with wax, egg, and other herbs to treat inflammation and fever.

They used hair to suture cuts and scrapes, and Friar Bernardino de Sahagún described a casting process:

The broken bones were carefully set and the limb placed between splints of wood, tied tightly with cord. A plaster then was applied to the break, composed of gum of the ocozotl tree and resin and feathers. The limb and the splints together were encased in a second covering of rubber-like gum.

Aztecs Made An Effort To Keep Their Teeth Clean With Wood Ash, Honey, Salt, And Urine

As part of maintaining cleanliness, Aztecs used salt and urine to clean their teeth. Other materials like ashes, honey, roots, and barks were also used. To keep their breath fresh, Aztec women were known to chew a gum thought to be a mixture of chicle – derived from the sapodilla tree – and bitumen.

When friar and chronicler Bernardino de Sahagún tried the substance, he said, “[It] tireds one’s head; it gives one a headache.” He also said when a woman chewed tzictli, the Aztec word that has become chicle, she made “a clacking noise with her teeth like castanets.”

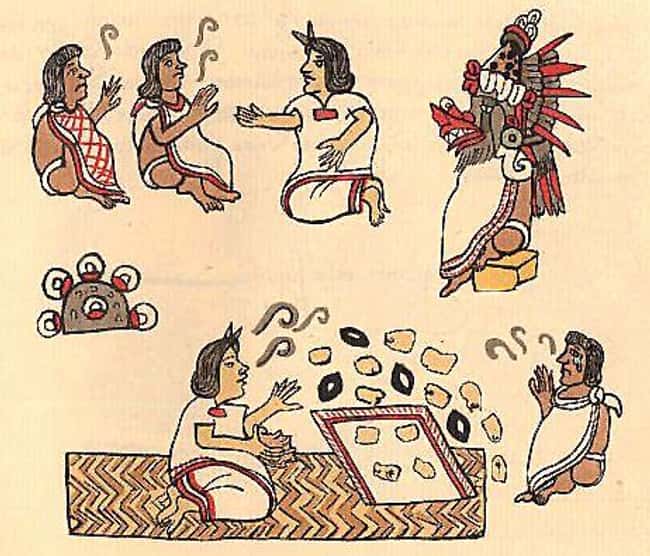

Aztec Dentists May Have Used A Concoction Of Vinegar And Rattlesnake Venom To Remove Patients’ Teeth

As a remedy to toothaches and infection, Aztecs could rub charcoal on their teeth but, if the tooth problem got too advanced, removing it was a necessity. Dentists could pull a tooth but not before applying a mixture of vinegar and snake venom. This made for a relatively painless tooth removal, after which a mixture of herbs was applied to protect and cure the open wound.

Aztec dentists also filed teeth, filled cavities, and applied jewels to incisors, while “ladies of the night” dyed their teeth red or black to distinguish themselves.

Public Workers Collected ‘Night Soil’ Daily Since It Was Unlawful For People To Dump Sewage Into Lakes And Streams

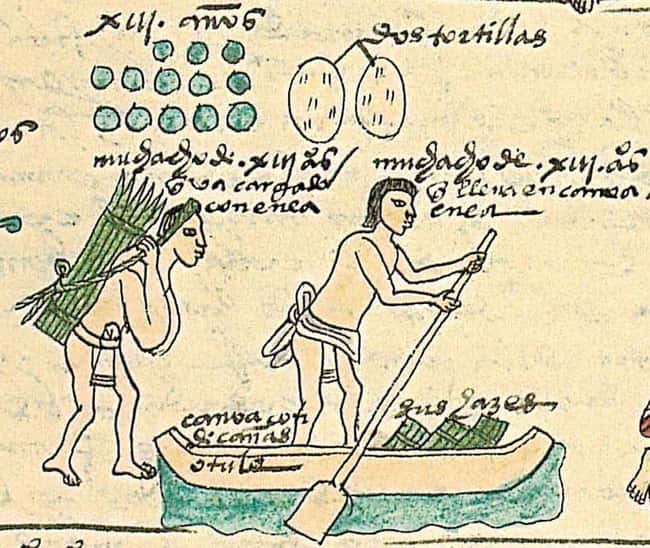

“Night soil” was human waste gathered from cities by Aztec workers and taken by canoe to fields and gardens for agricultural purposes.

But collecting night soil served multiple purposes. It was a practice that met Aztec standards of cleanliness by keeping excrement out of lakes and canals, as well as fulfilling the empire’s desire to prevent unnecessary waste while also bringing vital fertilizer to chinampas, or floating parcels of land upon which Aztecs grew many of their crops.

The intricate system of canals and aqueducts helped keep human waste from contaminating the water supply.

The Streets Of Tenochtitlán Were Swept Regularly And Lined With Public Toilets

Networks of canals in Aztec cities made keeping heavily populated areas clean much easier. When the streets of Tenochtitlán, for example, were swept, the detritus and dirt could be thrown into one of the canals that removed waste from the city.

Sweeping and cleanliness was a fundamental part of maintaining order in Aztec society. Women swept their homes every morning as a way to honor domestic space , while priests swept temples and schools to keep out unwanted and potentially threatening forces.

Cities also had public toilets available , the waste from which would be collected and used as fertilizer . It could also be channeled out of the city by one of the canals or other waterways.

Men Could Visit Barber Shops And Women Could Dye Their Hair At Home

As Hernán Cortés explored Tenochtitlán, he observed, “Establishments like barbers’ where [residents go to] have their hair washed and are shaved.” Hairstyles for men in the Aztec empire varied significantly, with priests keeping long locks – sometimes matted with soot – and common men wore their hair short.

Boys were shorn until the age of 10. At that point, they grew out a patch of hair on the backs of their heads, only shaven once they’d proved themselves to be a successful warrior.

Women could dye their hair, using, “black mud or a green herb called xiuhquilitl that produced a purple shining in the hair.” Some women shaved their heads completely while older females, particularly mothers, had long hair, divided at the nape of the neck and pulled back with a cord.

Clay could also be used after the hair was treated for dandruff – a complaint that led to a urine cleaning and hearty scrubbing with ground avocado pits – to bring color back to one’s locks. In the event of scabies, men and women had their heads shaved and, again, were doused in urine and herbal mixtures of pinewood, cottonseed, and avocado to eliminate the pests.

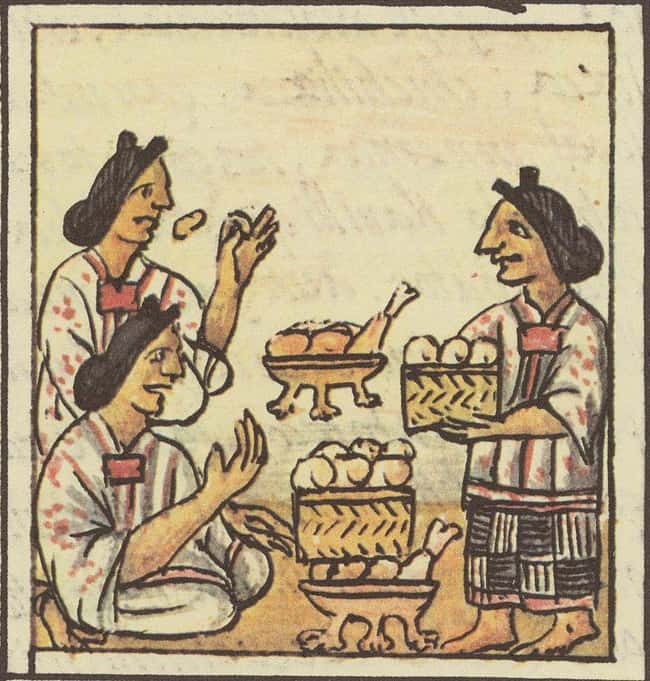

Feasts Started And Ended With Clean Hands

–

The Aztecs ate two meals per day, a breakfast and an afternoon supper. Sometimes, a late evening could mean an additional helping of gruel but, for upper-class members of society, a feast in the evenings could lead to a night full of food, entertainment, and excess. Fine dining started with clean hands:

When they had all come, they were given water for washing their hands and then the meal was served. Once this was done, they washed their hands again and their mouths and then cocoa and pipes were handed out.

Ruler Moctezuma, known for his adherence to personal cleanliness, took part in this ritual alongside his guests, as “four very beautiful, very clean women gave him water for his hands in the deep basin which they call xicales.”

–

(For the source of this, and many other4 equally interesting and intriguing articles, please visit: https://www.ranker.com/list/aztec-hygiene/melissa-sartore/)