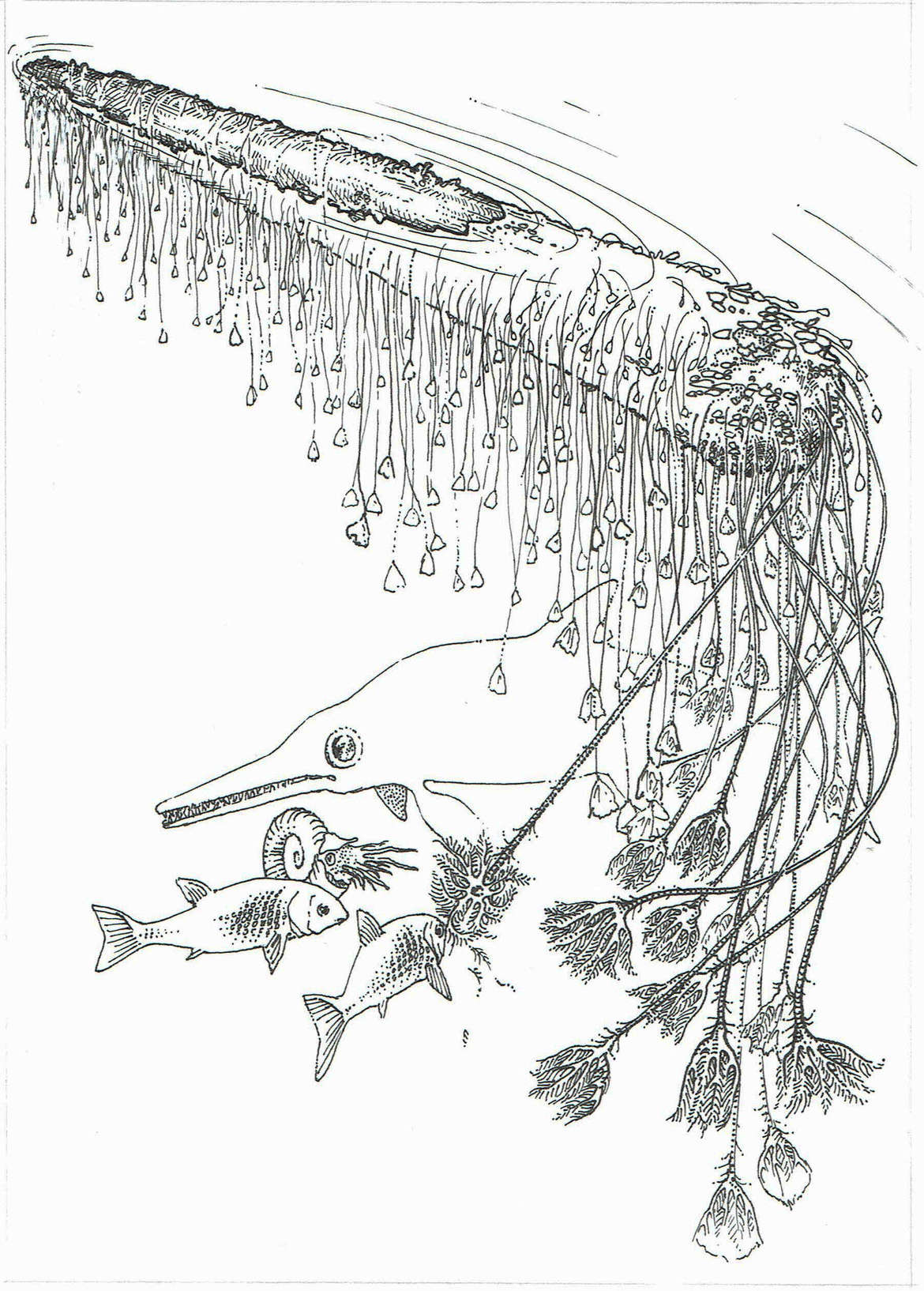

Jurassic seas were swimming with strange life forms. Crinoids could have passed for extras in Little Shop of Horrors if it had an aquarium, and eerier still, these creatures without a brain somehow figured out how to attach themselves to pieces of driftood that functioned as rafts to carry them across ancient waters.

Crinoids are marine invertebrates related to starfish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and other things that could show up in your nightmares. Few of these echinoderms remain today. The extinct species Seirocrinus, otherwise known as the sea lily, floated across the open sea in colonies that thrived off a lifestyle that took them far and wide for up to 20 years, as new research has found. Fossils first unearthed in England revealed what looked to be crinoids attached to pieces of driftwood. Until now, it hasn’t been clear whether (or how long) the creatures held on.

–

“It’s a case of survival,” Aaron Hunter, co-author of a study recently published in Royal Society Open Science, told SYFY WIRE. “The crinoid larvae need a hard surface and good supply of food to survive and grow. At the time these crinoids lived, the sea bed was effectively dead due to low oxygen. So over time this species radically adapted to this mode of life.”

180 million years ago, there was a shortage of oxygen on the seafloor, where crinoids and their surviving relatives would usually stay anchored. They are usually benthic—living at the bottom of the sea. However, these filter-feeders needed to escape a period of dysoxic conditions that basically made the bottom of the ocean a dead zone. It was then that the sea lilies took on a pseudoplanktonic (floating around freely but still attached to something) lifestyle by grabbing onto driftwood that took them to new sources of food and away from anything that would look at them as food.

“Forming raft colonies took them away from predators on the sea bed and in shallow water areas,” said Hunter.

The colonies could number over a hundred crinoids, the only fossilized examples of the many passengers on a piece of driftwood that was probably already crowded with the ancestors of limpets and barnacles. They would strategically position themselves on the back end so they would not get the brunt of waves and currents. Hunter and his team used spatial point process analyses (SPPA) to see whether sea lilies would colonize the logs while they were afloat or whether their rafts had docked on something first before they came on board. Diffusion models compared small, medium, and large crinoid clusters to see how long the floating colonies survived.

“There are differences in the patterns of ecological and environmental distribution that tell us which has the greatest influence,” Hunter said of how he and his colleagues investigated the formation and longevity of these colonies on the largest known fossilized specimen.

Some descents of Seirocrinus still colonize on pieces of driftwood today, but those colonies usually won’t last over 6 years because the wood is often infested with bivalves (like shipworms) that burrow inside and make it more susceptible to sinking. These bivalves did not yet exist during the early Jurassic. Where the crinoids in the fossil colony were positioned told Hunter and his team how larvae could have spread out, under what environmental conditions they clung to the wood, and whether they were surrounded by ideal conditions to make it to adulthood. Which tree the driftwood fell from also had an impact on survival at sea.

“How long the colonies endured is due to the type of wood (most likely a conifer) and the lack of boring bivalves that evolved after the Jurassic that tend to destroy wood on these rafts today as well as on wooden ships,” said Hunter.

Just think—crinoids somehow sensed where they had the best chance of staying alive, sought it out, rode the waves, and did it all without a brain.

–

–

(For the source of this, and other wildly interesting articles, please visit: https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/crinoids-with-no-brain-made-their-own-rafts/)