–

From the medieval fashion for pointy shoes to Victorian waist-squeezing corsets and modern furry onesies, what we wear is a window to our past.

Now researchers say they have found some of the earliest evidence of humans using clothing in a cave in Morocco, with the discovery of bone tools and bones from skinned animals suggesting the practice dates back at least 120,000 years.

Dr Emily Hallett, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, the first author of the study, said the work reinforced the view that early humans in Africa were innovative and resourceful.

–

“Our study adds another piece to the long list of hallmark human behaviors that begin to appear in the archaeological record of Africa around 100,000 years ago,” she said.

While skins and furs are unlikely to survive in deposits for hundreds of thousands of years, previous studies looking at the DNA of clothing lice have suggested clothes may have appeared as early as 170,000 years ago – probably sported by anatomically modern humans in Africa.

The latest study adds further weight to the idea that early humans may have had something of a wardrobe.

Writing in the journal i Science, Hallett and colleagues report how they analyzed animal bones excavated in a series of digs spanning several decades at Contrebandiers Cave on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. The cave has previously been revealed to contain the remains of early humans.

Hallett said she began studying the animal bones in 2012 because she was interested in reconstructing the diet of early humans and exploring whether there had been any changes in diet associated with changes in stone tool technology.

However, she and her colleagues found 62 bones from layers dating to between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago that showed signs of having been turned into tools.

–

While the purpose of many of the tools remains unknown, the team found broad, rounded end objects known as spatulates that were fashioned from bovid ribs.

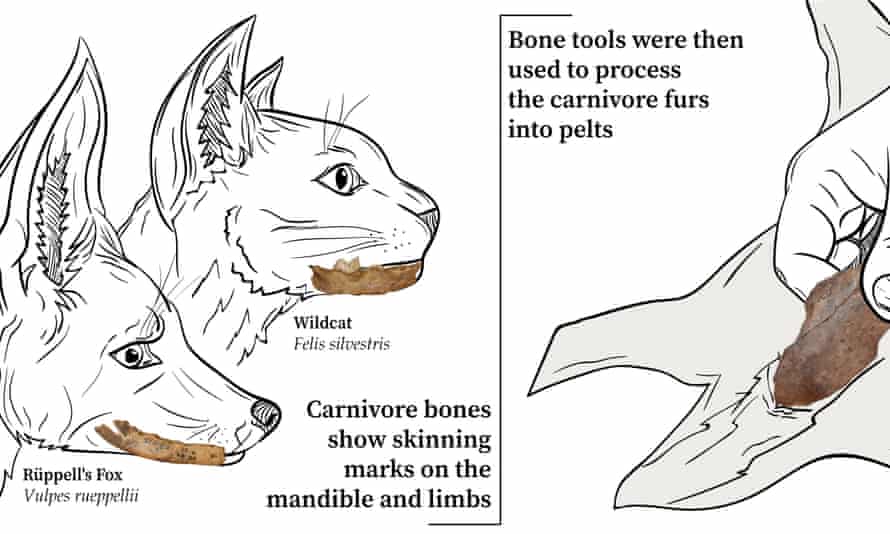

“Spatulate-shaped tools are ideal for scraping and thus removing internal connective tissues from leathers and pelts during the hide or fur-working process, as they do not pierce the skin or pelt,” the team write.

Sand fox, golden jackal and wildcat bones held further clues, showing cut marks associated with fur removal.

The team also found a whale tooth, which appeared to have been used to flake stone. “I wasn’t expecting to find it since whale remains have not been identified in any Pleistocene contexts in north Africa,” said Hallett.

While Hallett said it was possible the bone tools could have been used to prepare leather for other uses, the combined evidence suggests it is likely – particularly for fur – that the early humans made clothes.

But mysteries remain including what the resulting outfits would have looked like, and whether they were primarily used for protection against the elements or more symbolic purposes.

Hallett added that she believed European Neanderthals and other sister species were making clothing from animal skins long before 120,000 years ago – not least as they lived in temperate and cold environments.

“Clothing and the expanded toolkits of early humans are likely parts of the package that led to the adaptive success of humans and our ability to succeed globally and in climatically extreme regions,” she said.

Dr Matt Pope, an expert on Neanderthals at the UCL Institute of Archaeology who was not involved in the study, said clothing almost certainly had an evolutionary origin before 120,000 years ago, noting among other evidence finds of even older stone scrapers, some with traces of hide working.

But, he added, the new research suggested Homo sapiens at Contrabandiers Cave, like Neanderthal people from sites such as Abri Peyrony and Pech-de-l’Azé in France, were making specialized tools to turn animal hides into smooth, supple leather – a material that could also be useful for shelters, windbreaks and even containers.

“This is an adaptation which goes beyond just the adoption of clothing, it allows us to imagine clothing which is more waterproof, closer-fitting and easier to move in, than more simple scraped hides,” said Pope. “The early dates for these tools from Contrebandiers Cave help us to further understand the origins of this technology and its distribution among different populations of early humans.”

–