The region’s air typically doesn’t suit strikes – so they have become an important climate crisis indicator.

Thunderstorms need moisture, instability and lift. Disappearance of sea ice means more water is able to evaporate, adding moisture to the atmosphere. Photograph: Dimitar Kyosemarliev/Reuters

Thunderstorms need moisture, instability and lift. Disappearance of sea ice means more water is able to evaporate, adding moisture to the atmosphere. Photograph: Dimitar Kyosemarliev/Reuters

–

By Léonie Chao-Fong

Last modified on 2022 Jan 07

–

The high Arctic saw a dramatic rise in lightning in 2021 in what could be one of the most spectacular manifestations of the climate crisis.

In a region where sightings were once rare, the Earth’s northernmost region saw 7,278 lightning strikes in 2021 – nearly double as many as the previous nine years combined.

Arctic air typically lacks the convective heat required to create lightning so the latest findings, published in the Finnish firm Vaisala’s annual lightning report, have scientists like Vaisala’s meteorologist and lightning applications manager, Chris Vagasky, worried.

“Over the last 10 years, overall lightning counts north of the Arctic Circle have been fairly consistent,” Vagasky said. “But at the highest latitudes of the planet – north of 80° – the increase has been drastic. Such a significant shift certainly causes you to raise your eyebrows.”

Three things are required to generate thunderstorms – moisture, instability and lift. The disappearance of sea ice means more water is able to evaporate, adding moisture to the atmosphere. Higher temperatures and atmospheric instability create the perfect conditions for lightning. Monitoring how lightning trends change in the Arctic can therefore reveal a lot about how the atmosphere is changing in response to shifts in climate.

“Changes in the Arctic can mean changes in the weather at home,” Vagasky said. “All weather is local, but what happens at your house depends on how the atmosphere is behaving elsewhere throughout the world. Changes to conditions in the Arctic could cause more extreme cold outbreaks, more heatwaves, or extreme changes in precipitation to Europe.”

The devastating wildfires that raged across Europe and North America last summer were at least in part sparked by lightning. Typically less than 15% of wildfires in any given year are caused by lightning, but these fires burn more acreage than human-caused fires. Identifying the conditions favorable for lightning-triggered wildfires is crucial to react quickly to strikes.

The risk of being hit by lightning in the Arctic is still low, but the increased probability of lightning could threaten communities that have not had to deal with frequent lightning in the past. People on the flat tundra or ocean are vulnerable to lightning strikes, and lightning puts electrical and other infrastructure at risk of damage.

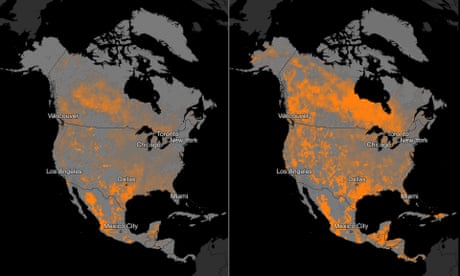

In the US, which saw the second-highest number of lightning strikes in 2021 after Brazil, Vagasky and his team tracked more than 194m incidences – 24m more than observed in 2020. A 2014 study forecast a 12% increase in the frequency of lightning strikes with every one degree Celsius increase in temperature.

“A changing climate may increase the potential for lightning-triggered wildfires,” Vagasky said. “Scientists can’t tie a lightning strike from one day to the changes in our climate, but monitoring trends of lightning in the Arctic is especially important and something that will need to be studied now and in the future.”

–

–

An erosion of democratic norms. An escalating climate emergency. Corrosive racial inequality. A crackdown on the right to vote. Rampant pay inequality. America is in the fight of its life. You’ve read many articles in the last year, making you one of our top readers globally. If you can, please make a gift today to fund our reporting in 2022.

For 10 years, the Guardian US has brought an international lens with a focus on justice to its coverage of America. Globally, more than 1.5 million readers, from 180 countries, have recently taken the step to support the Guardian financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent. We couldn’t do this without readers like you.

With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we can set our own agenda and provide trustworthy journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence, offering a counterweight to the spread of misinformation. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favor. It is reader support that makes our high-impact journalism possible and gives us the energy to keep doing journalism that matters.

Unlike many others, Guardian journalism is available for everyone to read, regardless of what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality.

We aim to offer readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events shaping our world. We are committed to upholding our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.

Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. Thank you.