A new study has found that fertilizer made from sewage sludge and used widely in agriculture operations is introducing vast amounts of microplastics into Europe’s soils. Depositphotos

A new study has found that fertilizer made from sewage sludge and used widely in agriculture operations is introducing vast amounts of microplastics into Europe’s soils. Depositphotos

–

By Nick Lavars

Sewage sludge serves as an appealing and sustainable source of fertilizer, for both large-scale agriculture operations and home gardeners. But studies are starting to illustrate that its contents may not be entirely benign, neither for the environment or living organisms.

A study published last year that analyzed home fertilizer products found unsafe levels of toxic PFAS “forever chemicals” in every sample. That research found that typical sewage treatment methods don’t break down these persistent chemicals, and as sludge is widely applied to lands across the US, it introduces huge amounts of them to food crops and waterways.

This new study was carried out by scientists at Cardiff University and the University of Manchester and focused on the farmlands of Europe, and the risks posed to them by fertilizers made from sewage sludge. The work involved analyzing samples from a wastewater plant in Newport, South Wales, which treats sewage from a population of around 300,000.

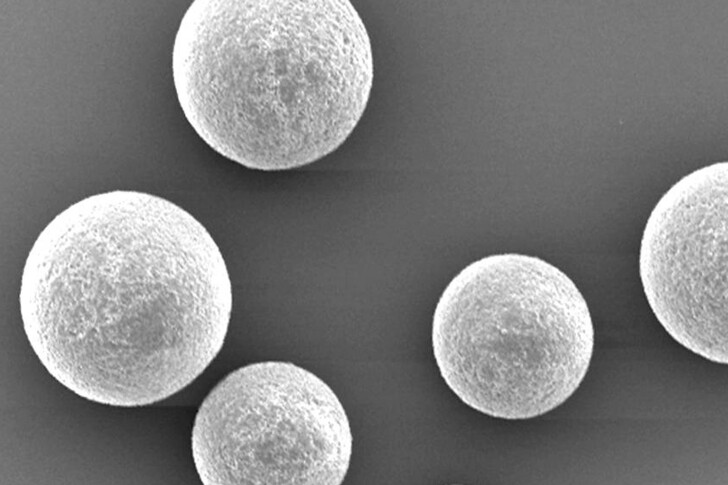

This showed that the plant was collecting larger plastic particles between 1 and 5 mm in size with a 100-percent strike rate, preventing them from slipping through into the waterways. Each gram of the sewage sludge created through this process, however, was then found to contain up to 24 microplastic particles, amounting to around one percent of its total weight.

The scientists then extrapolated on this by using data on the use of sewage sludge as a fertilizer across the continent from the European Commission and Eurostat. This indicated that somewhere between 31,000 and 42,000 tons of microplastics, or many trillions of particles, are being applied to the soils of Europe each year. According to the authors, this rivals the concentration of microplastics in the surface waters of the ocean.

“Our research questions whether microplastics are in fact being removed at wastewater treatment plants at all, or are effectively being shifted around the environment,” said lead author of the study James Lofty, from Cardiff University’s School of Engineering. “A clear lack of strategy from water companies to manage microplastics in sewage sludge means these contaminants are transported back into the soil and will eventually return to the aquatic environment.”

The findings offer new insights into the way microplastics migrate around the environment, but perhaps aren’t all that surprising in light of recent research in the area. A 2018 study found microplastics in human stool samples all around the world, and we’ve also seen scientists discover plastic particles in the human bloodstream and deep in the lungs for the first time. Other research has demonstrated how microplastics in wastewater treatment plants can foster the growth of superbugs, and how they can carry dangerous pathogens far out to sea.

“Our results highlight the magnitude of the problem across European soils and suggest that the practice of spreading sludge on agricultural land could potentially make them one of the largest global reservoirs of microplastic pollution,” said Lofty. “At present, there is currently no European legislation that limits or controls microplastic input into recycled sewage sludge based on the loads and toxicity of microplastic exposure.”

The research was published in the journal Environmental Pollution.

Source: Cardiff University

–

–