The Coen brother goes solo to put together a documentary about the shamanic wild man of early rock’n’roll, who reinvented himself as a country and gospel act.

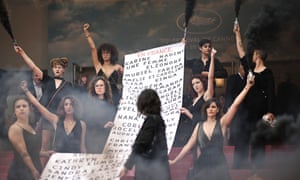

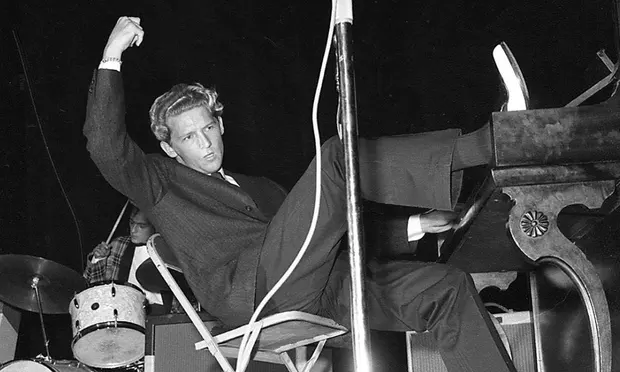

Wild man … Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind. Photograph: AP–

Wild man … Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind. Photograph: AP–

Last modified on 2022 May 22

–

The Coen brothers temporarily parted ways for solo projects on haunted charismatic wrongdoers: for Joel it was Macbeth, for Ethan it has turned about to be insurgent rock’n’roll legend Jerry Lee Lewis, the shuddering, quivering Pentecostal shaman of the devil’s music, who is still alive at the age of 86.

Coen has put together a thoroughly enjoyable documentary composed entirely of archive footage of Jerry Lee throughout the years and his interviews and performances, starting with his sensational beginnings in the 1950s, leading to his cancellation in 1957 on the grounds of getting married – of all the sweetly old-fashioned things – to his 13-year-old cousin Myra Gale Brown. With cheerful impenitence, Jerry Lee is shown correcting an interviewer: Myra was one day shy of her 13th birthday on their wedding day so she was actually twelve.

Long years in the touring wilderness followed, doggedly tending to his US fanbase coast-to-coast, before Jerry Lee cunningly and successfully reinvented himself as a country singer, and an extravagantly sincerely gospel performer: personalities which co-existed with multiple marriages and drink and drug abuse issues.

In the amazing 50s footage Jerry Lee looks like the most terrifying Batman villain: the Riddler, perhaps, with his unfurled ringlets of blond hair that flew back from his head as he clattered the notes with those straight, splayed fingers for Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On, kicked the stool back and crashed a dissonant heel down on the keyboard. In his later, country incarnation in the 70s with more measured style and subdued hair, Jerry Lee is shown performing Whole Lotta Shakin’ again, and it sounds even more predatory. No one made the line “we got chicken in the barn” sound more horribly unwholesome. He would still periodically go into the weird marionette playing style, bending his forearms up at the elbow, alternating to bring his fists down.

Like Elvis and all white rock’n’roll legends, Jerry Lee had an unpayable debt to black music and great black performers like Little Richard; Coen doesn’t mention it, but there’s also an obvious link between Jerry Lee and Liberace, the same weirdly coy up-through-the-lashes glance at the audience that’s created when you look at them from the keyboard. Elvis’s instruments were the mic stand and the guitar, which lend themselves more directly to pelvis-gyrating sexiness. With the piano it’s different – you have to launch yourself crazily away from it, as if moved by the spirit.

Jerry Lee always looked like a carnival barker and a televangelist – much more so than his cousin Jimmy Swaggart, who actually was a televangelist. He looks completely different for a BBC TV interview he gave to my colleague Richard Williams on The Old Grey Whistle Test: Jerry Lee had a beard, because he was preparing to play Jesus in a planned movie called The Carpenter. Sadly, I can find no record of that film ever getting made – what a remarkable performance Jerry Lee would surely have given. There is also a fascinating audio recording of a conversational Jerry Lee had with Sun Records founder Sam Phillips, in which he confessed his agonising fears about the state of his immortal soul.

This documentary does something very few films can: it makes you grin with pleasure.

Topics

Most viewed

More from Culture

-

–