Animal research has found any kind of sound blunted pain as long as it was played very softly. Depositphotos

Animal research has found any kind of sound blunted pain as long as it was played very softly. Depositphotos

–

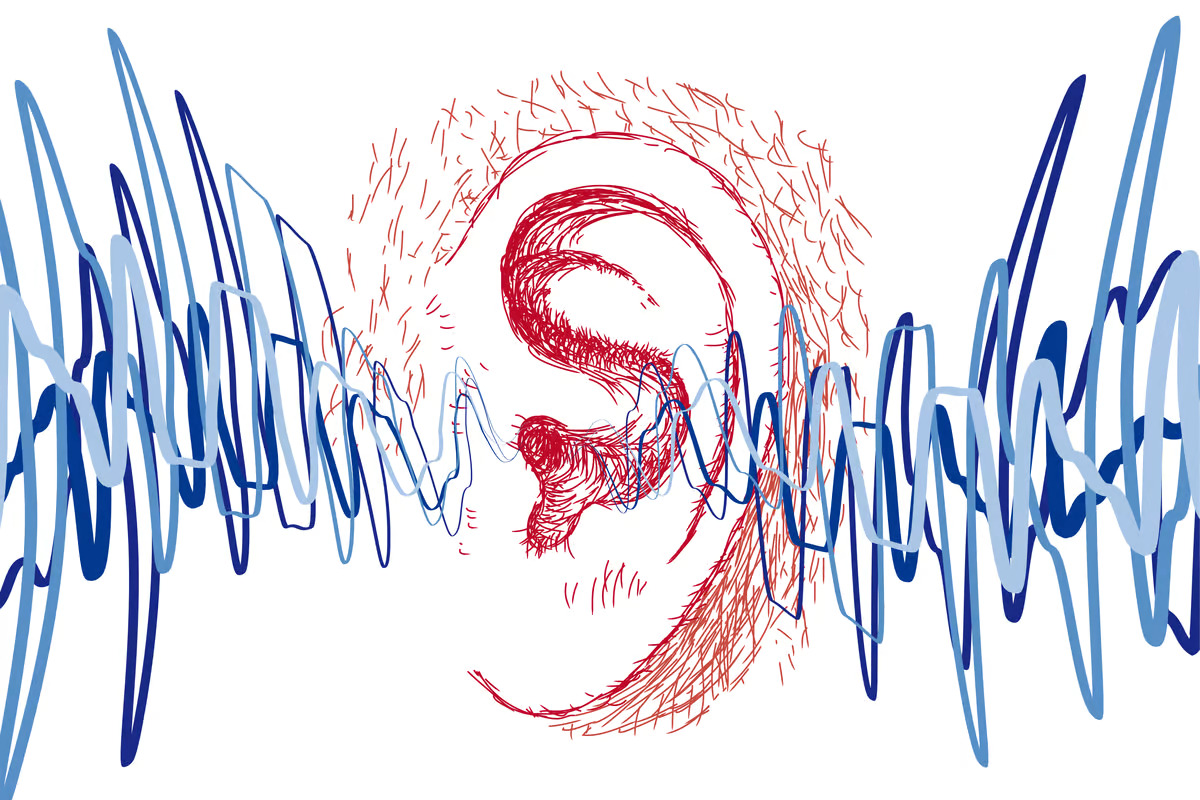

In 1960 a dentist named Wallace Gardner published an unusual study purporting to use sound for pain relief. He reported conducting more than 200 tooth extraction procedures using sound as the only analgesic agent. His study also cited eight other dentists who successfully used what was then dubbed “audio analgesia.”

Since then, the phenomenon has been replicated a number of times by researchers all over the world, but little is known about how the brain could actually be producing these analgesic effects. Yuanyuan Liu, co-senior author on the new research, said prior studies have hinted at brain mechanisms that could be at play but this new work homes in on the actual neural circuitry for the first time.

“Human brain imaging studies have implicated certain areas of the brain in music-induced analgesia, but these are only associations,” said Liu, from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. “In animals, we can more fully explore and manipulate the circuitry to identify the neural substrates involved.”

First, the researchers tested the common idea that pleasant classical music could have intrinsic analgesic properties. Mice were played a piece of music called Réjouissance by Johann Sebastian Bach while being injected with a solution in their paws to test pain thresholds.

Across difference experiments the volume of the music was increased in 5-db increments. The first surprise of the study came with the discovery that the only volume effective as an analgesic was the quietest – at 50 db, just 5 db above the ambient volume of the room.

The next test looked at different kinds of sound. So instead of classical music, the same experiments were conducted using white noise and a version of the classical piece pitch-shifted to sound unpleasant. Here the researchers came across the second unexpected finding – all sounds generated analgesic effects in the animals.

The only influential factor was volume. Essentially, any kind of sound worked if it was played at a volume just a whisper louder than the ambient room noise.

“We were really surprised that the intensity of sound, and not the category or perceived pleasantness of sound would matter,” Liu added.

Finally, the researchers set out to uncover exactly which neural circuits seemed to be generating these sound-influenced analgesic effects. Using a number of sophisticated techniques to zoom in on active neural pathways, the researchers discovered a direct pathway between the auditory cortex and the thalamus.

Low-intensity sound seemed to blunt neural activity at the thalamus end of this pathway, and subsequent tests suppressing activity in this pathway using methods other than sound led to similar pain-reduction outcomes. Interestingly, this suggests the research has identified a mechanistic pathway by which sound directly reduces pain sensations.

The finding perhaps validates Gardner’s study from 60 years ago, which presciently hypothesized music directly blunted the felt experience of pain by potentially disrupting communication between auditory brain systems and the thalamus.

“In thinking toward an explanation, we note that parts of the auditory and pain systems come together in several regions of the reticular formation and lower thalamus,” Gardner wrote in 1960. “The interactions between the two systems are largely inhibitory. Both the direct suppressive effect and the effects mediated through relaxation, reduction of anxiety, and diversion of attention, can be explained by assuming that acoustic stimulation decreases the ‘gain’ of pain relays upon which branches of the auditory system impinge.”

In a commentary on the new study, researchers Rohini Kunar and Thomas Kunar indicate the findings somewhat contradict prior hypotheses that argue sound-induced anesthesia in humans may be solely due to psychological factors such as being calmed or distracted by music.

“Previous concepts on using music and sounds for pain relief attributed their effects to distraction-associated analgesia and reduction of anxiety,” the pair of researchers noted. “Although sound likely contributes to distraction, the study by Zhou et al. reveals that sound-induced analgesia is a specific mechanistic entity in its own right, supported by the observation that suppression of pain outlasted the application of sound by several days.”

Nevertheless, Liu is cautious not to discount those other psychological factors. He does point out music is much more complex for humans than rodents, with elements such as nostalgia, memory and pleasant harmony possibly playing relevant roles in any analgesic effect.

“We don’t know if human music means anything to rodents, but it has many different meanings to humans – you have a lot of emotional components,” Liu said.

Moving forward it will be crucial to first explore whether this neural circuit observed in mice also plays out in humans. And if it is validated then it could open the doors for a whole host of new non-pharmacological methods for pain control.

Speaking to Science, Harvard neurobiologist Clifford Woolf said the findings suggest low-volumes of noise could be useful analgesics instead of the more traditional idea of using calming classical music.

“Many would have anticipated you need to listen to Mozart to get pain relief,” said Clifford. “But maybe all we need to do is give patients a tiny level of buzzing noise.”

The new study was published in the journal Science.

Source: NIH

–

–