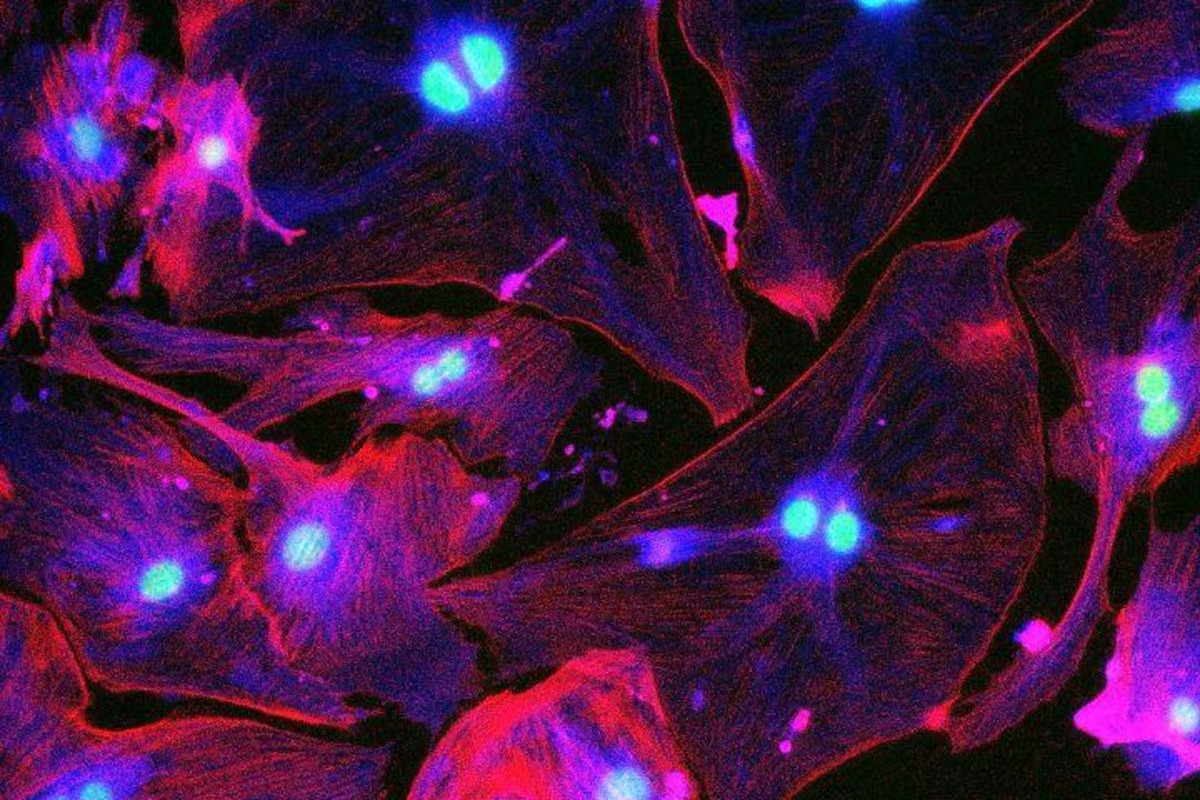

Senescent cells fluorescing under UV light. Nabora Reyes/Peng Lab

Senescent cells fluorescing under UV light. Nabora Reyes/Peng Lab

Over the decades of our lives, our cells accumulate DNA damage that eventually causes them to stop dividing. These so-called senescent cells are usually cleared out by the immune system, but as we get older they begin to accumulate in the body and, when they do, they secrete inflammatory compounds that affect tissues around them. This process has been linked to a range of aging symptoms, from wrinkles and gray hair to increased risk of diseases like diabetes and dementia.

Unsurprisingly, lately these senescent cells have become a major target for anti-aging research. A class of drugs known as senolytics are designed to clear out these “zombie cells,” and results have shown promise in reducing age-related diseases and even increasing lifespan and healthspan.

But there might be more to the story than we thought. In a new study, researchers at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) found that senescent cells can be found in young, healthy tissues in higher numbers than previously thought, and they seem to play a key role in promoting repair from damage.

The team developed a more effective method to image senescent cells by fusing a gene called p16, which is overly expressed in these zombies, with a fluorescent protein. This makes the cells glow bright green under UV light, allowing them to be seen more clearly than previous fluorescence techniques.

Using this method, the team detected more senescent cells in young tissues, and even found evidence that they appear shortly after birth. They seem to secrete growth factors that stimulate stem cells to repair tissue damage, and this process can be activated in senescent cells by immune cells like macrophages and monocytes.

The team found that senescent cells tend to be located next to stem cells in “barrier” tissues – those that come into contact with the outside world, such as the lining of the lungs, intestines and skin, which need to be selective about which foreign substances to let in. Cell damage can occur at these interfaces, which may be why senescent cells are there to stimulate repair.

In tests in mice, the team administered a toxic compound to lung tissue, and found that mice that were treated with senolytic drugs – those that destroyed senescent cells – could no longer repair damage to the barrier surface of the lung tissue. While this finding doesn’t undo all the benefits that have been found in senolytics, it does raise questions about wiping out all senescent cells indiscriminately.

“The studies suggest that senolytics research should focus on recognizing and precisely targeting harmful senescent cells, perhaps at the earliest signs of disease, while leaving helpful ones intact,” said Leanne Jones, director of the UCSF Bakar Aging Research Institute. “These findings emphasize the need to develop better drugs and small molecules that will target specific subsets of senescent cells that are implicated in disease rather than in regeneration.”

The research was published in the journal Science.

Source: UCSF

–