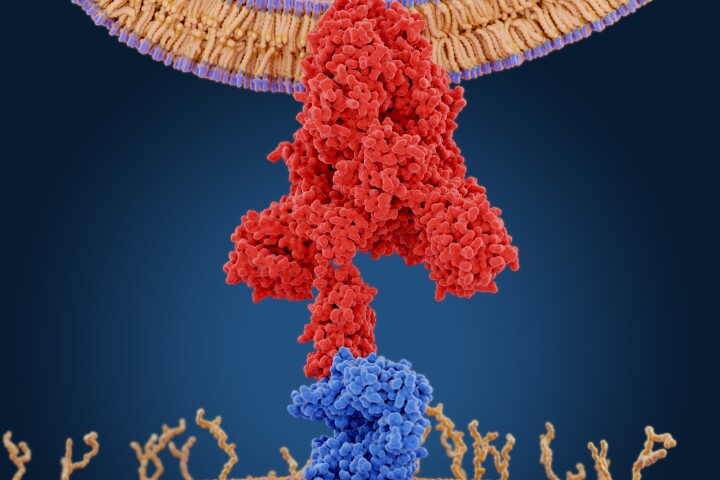

An artist’s impression of the ecosystem that lived in Greenland 2 million years ago, as revealed by the world’s oldest DNA samples. Beth Zaiken

An artist’s impression of the ecosystem that lived in Greenland 2 million years ago, as revealed by the world’s oldest DNA samples. Beth Zaiken

The maximum survival time of DNA has long been the subject of debate. It’s usually thought to degrade within a few thousand years, but under ideal conditions – very cold and very dry – the theoretical upper limit was set at about 1 million years. Last year, a team confirmed DNA could last at least this long with the discovery of mammoth DNA dating back 1.2 million years.

And now that record has been almost doubled. Scientists have discovered a sample of sediments in Greenland preserving environmental DNA (eDNA) dating back about 2 million years. The sample contains DNA fragments from many different animals, plants and microbes, providing an unprecedented snapshot of a complex ecosystem lost to time.

“A new chapter spanning one million extra years of history has finally been opened and for the first time we can look directly at the DNA of a past ecosystem that far back in time,” said Professor Eske Willerslev, co-lead author of the study. “DNA can degrade quickly but we’ve shown that under the right circumstances, we can now go back further in time than anyone could have dared imagine.”

The sediment deposit measured almost 100 m (328 ft) thick, which built up over 20,000 years inside the mouth of a fjord. This was then buried by permafrost, which protected and preserved the DNA samples for 2 million years.

Inside this deposit the researchers were able to identify 41 separate, usable DNA samples, which were then cross-checked against extensive libraries of DNA samples from present day organisms. From this, the team was able to identify many of the species that called ancient Greenland home.

The researchers detected DNA from reindeer, hares, lemmings, rodents, geese, and even marine animals like horseshoe crabs. Surprisingly, the team also found traces of mastodons, a relative of mammoths that were previously only thought to have lived in North and Central America. These creatures lived among birch, poplar and thuja trees, as well as other shrubs and herbs. Bacterial and fungal DNA was also detected.

Some of these DNA fragments were clearly identified as predecessors to modern species, while others could only be identified at the genus level. Most intriguingly of all, some DNA samples couldn’t be identified at all amongst still-living species. Many of the samples were collected as far back as 2006, but the scientists had to wait for technology to catch up.

“It wasn’t until a new generation of DNA extraction and sequencing equipment was developed that we’ve been able to locate and identify extremely small and damaged fragments of DNA in the sediment samples,” said Professor Kurt H. Kjær, co-lead author of the study. “It meant we were finally able to map a two-million-year-old ecosystem.”

The team says that the new discovery could indicate that extremely old DNA could be preserved in other parts of the world, revealing incredible new insights into evolution.

The research was published in the journal Nature.

Source: University of Cambridge via Scimex

–